Author: Phoebe Wilkins

Recently Australia stopped what they were doing for one minute to remember the men and women who put their lives on the line in the name of their country.

At 11am on 11 November we stop to remember our diggers, our patriarchs and matriarchs who enlisted in wars for the betterment of their Australia.

During this time, inevitably news pieces crop up about the tragedies and triumphs of our diggers, the untold stories about their heroics in the line of fire. However, one story grabbed my attention in particular. When we think about soldiers returning home after the battles, when they are shipped back to the home front due to injury or the eventual cessation of the hostilities, we think about joyous rapture to be away from the brutalities of war and back in the arms and comfort of their families and loved ones. What is not so frequently written or discussed is what the brutal nature of war can do to a soldier’s mental health. Whilst today, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is recognised as a real part of the repercussions of war, at the conclusion of the First and Second World War’s common phrases such as “shell shock” were used to describe the state in which soldiers returned home. In hindsight, these cases of “shell shock” could possibly have also been cases of PTSD or further mental health issues related to the trauma and brutality of war. So it was in a recent piece about the influx of returned soldiers to the Mont Park (Hospital for the Insane 1912-1934) which made me delve deeper into available records held at the Public Record Office Victoria (PROV).

Due to the nature of these records, the more recent files are closed under the privacy act, whereby if a record relates to a person this will be closed for 75 years from the date of creation (for adults) and for 99 years from the date of creation (for children). However, the timeframe in which I was looking was during and proceeding the years of the First World War. This time frame led me to unearth a box of records which relates specifically to the correspondence files of the ‘Military Mental Hospital’ at Mont Park.

These records are an insightful look into Mont Park Repatriation Hospital for returned soldiers and detail correspondence between such agencies as The Australian Red Cross Society, ‘the Lunacy Department’ and individuals seeking further information.

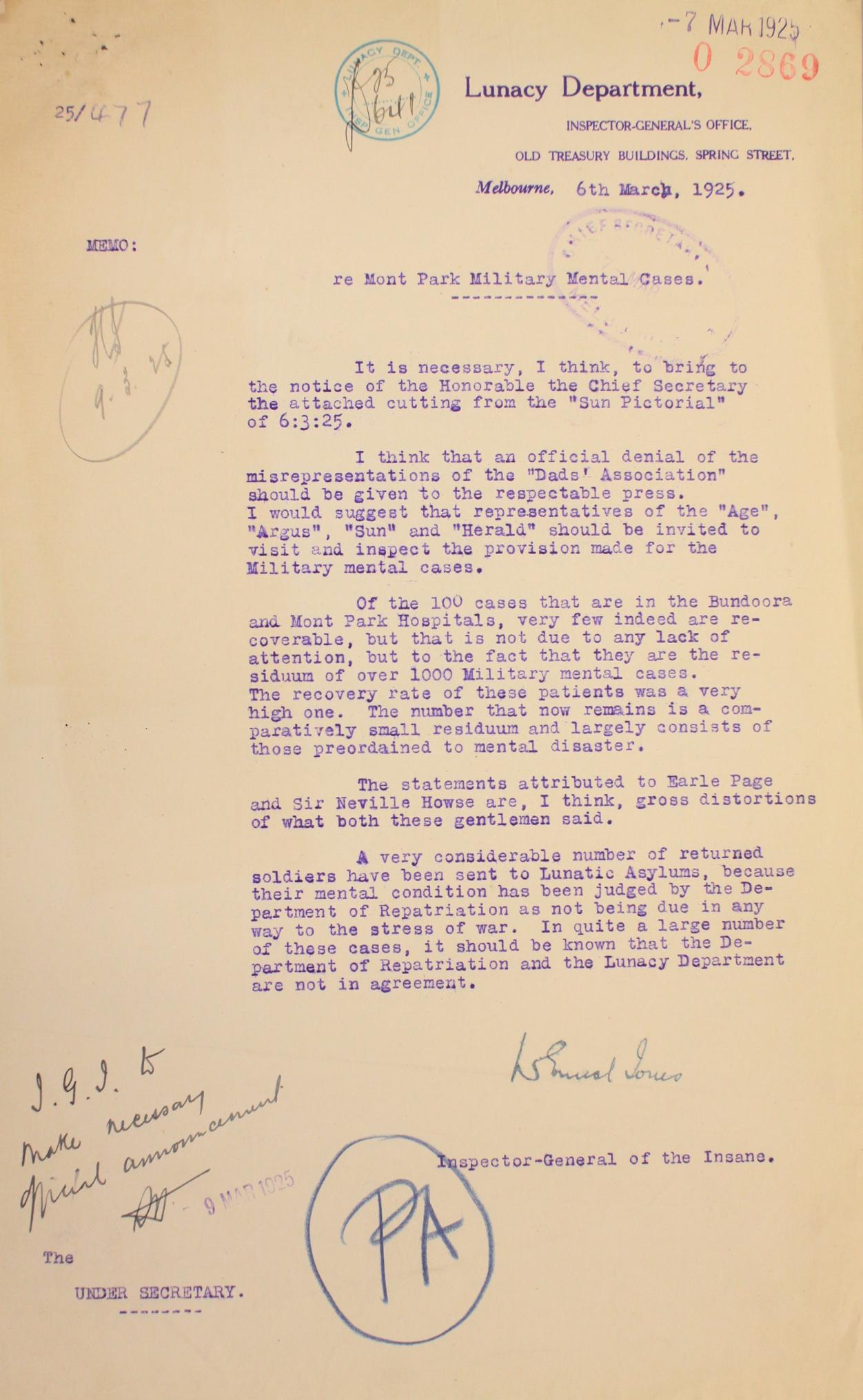

A few letters struck a particular cord; firstly the reply to a piece written to the editor of a newspaper in March 1925. This publication from the President of the Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Fathers’ Association of New South Wales was an objection relating to repatriated soldiers’ and ‘lunatics’ being housed together at Mont Park and Bundoora, thus slowing down the process of the returned soldiers’ recovery. The reply to this editorial piece came in the form of a letter from Dr. W. E. Jones. Inspector-General of the Insane. Dr. Jones stated that, ‘a very considerable number of returned soldiers have been sent to Lunatic Asylums, because their mental condition has been judged by the Department of Repatriation as not being due in any way to the stress of the war.’

Another piece of correspondence from a few years later in November 1927 ignited my interest. Dr. Jones wrote to the Deputy Commissioner in the Department of State Repatriation (Victoria) about one particular Private who had initially been voluntarily admitted to Bundoora, before being discharged and then subsequently immediately re-admitted under the Mental Treatment Act in 1925. The terse correspondence describes a battle between admitting the Private under the Mental Treatment Act rather than the Lunacy Act. Mr McPhee, the Deputy Commissioner argues that, ‘The Mental Treatment Act, it is understood, was introduced to protect the returned soldiers who became insane as the result of war service from the stigma of being certified as lunatics…’

These records are filled with correspondence relating to particular returned soldiers requesting leave, their mental capacity, queries from other Australian state departments as to the running of such institutions, and the disputes surrounding the reasons for soldiers needing to be housed in such institutions and classified as ‘lunatics’. It is an eye opening collection of correspondence which brings to light the aftermath of the bloody battle Australians fought to protect their King and country.

VA 2846 Mont Park (Hospital for the Insane 1912-1934; Mental Hospital 1934-c.1970s; Mental/Psychiatric Hospital c.1970s-ct.)

VPRS 7424 Nominal Register of Patients

VPRS 7527 Military Mental Hospital Correspondence Files

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples