Author: Natasha Cantwell

Communications & Public Programming Officer

The Grand Old Dame of Victoria's alpine region, Mount Buffalo Chalet, has been left in a precarious position since bushfires devastated the local tourism industry in 2006. Boarded up for the past fourteen years, this heritage-listed icon requires continual restoration to ensure it doesn’t succumb to the harsh mountain climate. While architecture and history enthusiasts across Victoria continue to fight for the future of this much-loved ski resort, let’s take a moment to look back to the beginning of Mount Buffalo Chalet’s story.

Mount Buffalo had been a favourite spot for adventurous skiers and dedicated naturalists since the late nineteenth century, but the remote and difficult terrain kept it out of reach for the average holidaymaker until 1908, when Victorian Premier, Thomas Bent earmarked Mount Buffalo National Park for wider tourism. That year the temporary status of the reserve was upgraded to permanent, the area expanded to 10,406 hectares, and a road built to the summit, making it now accessible by car or horse drawn buggy. The Age, covering the official proceedings for the road’s opening, described how the alpine experience was a novelty for many of those attending.

“Off the track the snow was in many places feet deep, and the gum trees wore a white mantle. To many the sight was a new one, which gave a sense of unreality, and when in the dying light of the day a snow storm came on, filling the air with fluttering white flakes, and covering umbrellas and coats with layers of snowy whiteness, the charm of the picture was complete.” 1

Now all Mount Buffalo needed was lodgings for these new tourists, who would have considered the existing huts and family-owned hotels a step too far out of their comfort zone. So, before the road was even finished, Bent unveiled an ambitious plan for a government hospice to accommodate the large numbers of visitors he anticipated. At a press conference, the Public Works Department’s chief architect George Austin announced that the hospice would be constructed from local granite and “the appearance of the building would be fine but rugged, in keeping with the rugged grandeur of the surrounding scenery.” 2

His sketches showed a formidable castle-like building in the Scottish Baronial style, but the interiors he described sounded cosy and inviting. Guests were envisioned relaxing in the drawing, smoking, billiard, reading and card rooms, secluding themselves in the lounge’s various inglenooks, or enjoying a hot drink in the coffee room that opened up into an attractive winter garden. When journalists asked the Premier if it would cost several thousand pounds, he replied, “Yes” 3 but didn’t elaborate, so newspapers were left to speculate. Their estimates ranged from £10,000 to £20,000.

These figures seemed to come as a surprise to those in charge, because by 1909 the government had backtracked, explaining that the cost of granite was much higher than they’d anticipated. That year’s change in leadership undoubtedly also had an impact, and Bent’s grand vision in stone became John Murray’s charming, but much more humble, Swiss-style chalet. Since the new design could no longer be described as rivaling the impressive scenery, it was instead promoted as providing a counterpoint.

“Externally the building is designed to give a home-like appearance, and is well suited to offer a broad contrast to the mighty and massive rocks that on all sides guard and shelter it from snow storms and rough winds.” 4

With a modest budget of £4000, local eucalyptus trees provided a cost-effective alternative to stone and Mount Buffalo Chalet ended up becoming Australia’s largest timber building. Logs were milled at a nearby site (now Grossmans Mill Picnic Area) but the sawmill required a constant water supply, so the Underground River was dammed at the entrance to Haunted Gorge, and Lake Catani was created. While it was essentially a practical solution to a construction problem, the lake was marketed to the public as part of government efforts to beautify the landscape and provide more recreational activities, such as ice-skating, boating and fishing.

The completion of the chalet was highly anticipated and Victorian newspapers updated their readers on the progress throughout construction, however not all reviews were glowing. There was resentment that the grand original design had not eventuated and skepticism over the use of wood, especially green wood, which required builders to take into consideration the shrinkage of the lumber that would happen as the wood dried out after construction. In January 1910, The Age wrote a scathing critique, attacking both the building techniques and the design. The writer was especially appalled at the plans for bedroom cubicles, which measured only eight by six feet, and featured internal walls that stopped short of the ceiling.

“When each of these absurd little boxes is fitted with a bedstead and the ordinary bedroom furniture, what room will there be for the occupants? What convenience and what privacy? A conversation conducted in one will be common to the whole flat, and, what is worse, any person if so inclined may hoist himself on to the partition, make an inspection of his neighbor's belongings, and generally make himself disagreeable to his full bent. The people who are ready to travel to the Buffalo, either for health, rest or pleasure, want something better than shabby accommodation like this, which would not be tolerated in a tenth rate boarding house.” 5

Construction also took longer than expected, due in part to a breakdown in the timber-cutting machinery. However, rather than turn away the tourists who were still keen to visit, the government set up a temporary campsite of tin sheds and tents in front of the construction site. It is estimated that 2,000 visitors lived in the camp in the six months prior to the opening of the new building. Accounts from the time note that although the amenities were crude, visitors enjoyed the unconventional situation and spirits were always high. Resourceful holidaymakers found it easy to entertain themselves, throwing parties such as the impromptu Easter ball in the chalet’s almost-finished ballroom. An article in The Ovens and Murray Advertiser about the Easter celebrations reports that guests created their own music and “a gay and light-hearted throng danced until long past the midnight hour.” 6 The highlight of the night was apparently an unexpected performance by a caveman-themed brass band in full costume, who “made sounds (by courtesy called music) emanate from instruments which had no prototypes in either ancient or modern times. The efforts of the band were greeted with loud applause, and a repetition was demanded.” 7

This enthusiasm for holidays at Mount Buffalo continued to grow once the chalet officially opened on 17 April 1910 and it proved to be so popular that further bedroom wings were added over the next four years. While it wasn’t without its issues (inadequate heating was a common complaint), overall it was considered a luxurious and comfortable retreat. However, it was the atmosphere, more so than the amenities, which brought visitors back year after year. It became known as a sociable place, where, after a strenuous day outdoors, strangers would gather together for a night of card tournaments, guessing competitions and charades. As The Independent observed in 1911:

“Visitors to the mountain have to depend on each other for their pleasure, and, truth to tell, they want little inducement to turn companionable.” 8

It was in Mount Buffalo Chalet’s cosy nooks and homely lounge rooms that both memories and friendships were made.

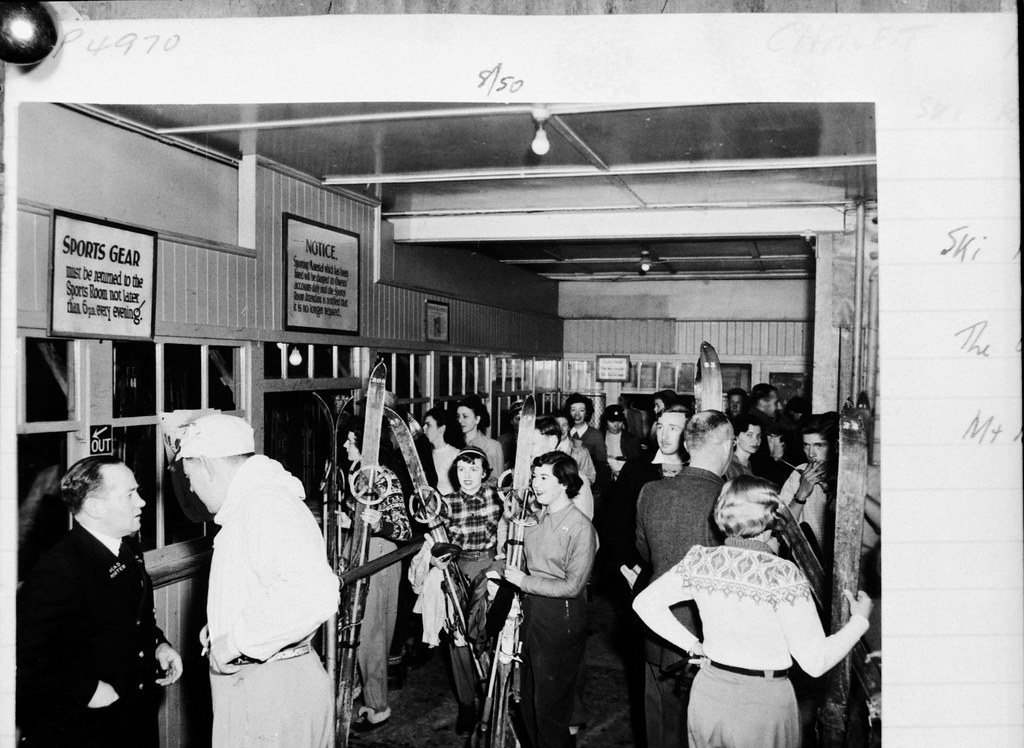

See more photographs and posters of Mount Buffalo Chalet from PROV's collection below. Hover over the image and click on the arrows to scroll through the album, or click on the picture to view on Flickr.

1. “Above the Snow Line” (1908, October 12). The Age (page 5). Retrieved from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/202183063

2 & 3. “Mount Buffalo” (1908, July 18). The Ovens and Murray Advertiser (page 4). Retrieved from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/200581179

4. “The Hospice on Mount Buffalo” (1909, October 16). The Leader (page 31). Retrieved from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/197078200

5. “The Grandeurs of Mount Buffalo” (1910, January 8). The Age (page 18). Retrieved from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/196078894

6 & 7. “Easter at Mt. Buffalo” (1910, April 16). The Ovens and Murray Advertiser (page 4). Retrieved from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/199706638

8. “At Mt. Buffalo” (1911, May 6). The Independent (page 1). Retrieved from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/73478133

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples