From the podcast series ‘Look history in the eye’

Written and presented by Katie Wood

Produced by Public Record Office Victoria

Music by Jack Palmer

Transcript

Natasha Cantwell

Look History in the Eye is produced by Public Record Office Victoria, the historic archive of the state government of Victoria, 100kms of public records about Victoria’s past are carefully preserved in climate-controlled vaults. We meet the people who dig into those boxes, look history in the eye, and bother to wonder why.

’m Natasha Cantwell, Communications and Public Programming Officer at Public Record Office Victoria. For today’s episode, we’re featuring a talk by Katie Wood. PhD candidate in history at Latrobe University and senior archivist at the University of Melbourne archives. Katie’s talk, which is titled ‘Pioneer girls and flappers’ was originally given as an online presentation for International Women’s Day 2022. It looks at the women who worked in Footscray’s munitions factory during WWI and earlier. It’s a story of poorly paid, dangerous work, but also the Knights of labor, Adella Pankhurst, cricket and woollen dresses, parades and funerals.

Katie Wood

Thank you Natasha.

So I’d like first of all to also acknowledge that I am speaking from stolen Wurundjeri lands and pay my respects to Elders past and present. And I’d also like to thank PROV for giving me the opportunity to talk about my thesis research. The chance to do so doesn’t come along very often and I hope you’ll find it all as interesting as I do.

The Public Records Office collections have been absolutely invaluable to my research as well as the work of the reference service and all the archivists who work to make their amazing collections accessible to researchers like me. And also before I begin, I’d also like to thank Peter for joining me in the presentation and if you haven’t been to the Living Museum of the West in pipemakers park down by the river, and you’re interested in this topic, then you’re really missing out and I recommend that you check it out online straight after this session.

So it was a fine September morning in 1897 and in the little valley on the banks of the Maribyrnong River near the Flemington Racecourse stood the huts of the Colonial Ammunition Company where young women had been churning out thousands of cartridges a day for the past five years. On this day, 50 young women had been at work for an hour and a half when their quiet seclusion was shattered. Some heard the sound of the cartridge exploding before the roof of the hut, known as number one filling room, was lifted high into the air by a tremendous explosion. The rest of the day was a chaotic mess of fires, debris and scattered cartridges, as firemen and doctors accompanied by a growing crowd of local residents, as news spread of the disaster.

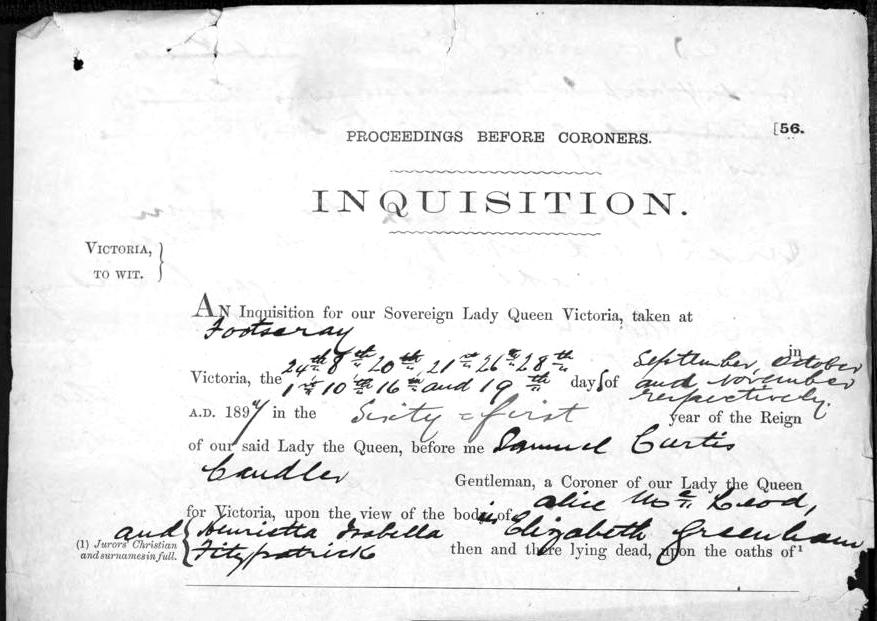

At the heart of it all were the three young women who had been filling cartridges in the hub. Nineteen-year-old Alice McLeod died instantly because she was working the capping machine that exploded. Nineteen-year-old Lizzie Greenham and seventeen-year-old Ettie Fitzpatrick were carried to the offices and died there later in the day from the horrific burns that they received.

Now I begin with this horrible incident to highlight just how dangerous the work of these young women was and also I think because the response to the fatalities shows also just how important that female workforce was to their community around Footscray.

So McLeod and Fitzpatrick were buried on the same day and their funeral processions met outside the Royal Hotel in Barkly Street and from there to the Melbourne General Cemetery, the whole way was lined with people. The procession extended half a mile in length and the gates to the cemetery were crowded with people. Because of media interest and the coronal inquest that followed we know something more of these individuals than most who worked at the Colonial Ammunition Company, which were called the CAC at the time. The fathers of all three were deceased as was Alice McLeod's mother. She lived with her grandmother, a brother and four sisters one of whom also worked at the CAC. And if we can take these similarities in the family experience of these women as probably common to the rest of the workforce as a whole it becomes clear I think that their work and their wages were central to family incomes. Beyond their households too, they had an important role to play in the politics and union organisation of the area in stark contradiction I think to the sort of biases and stereotypes of women at the time and making their story I think particularly pertinent to tell in relation to the themes of IWD this year.

The coronial inquest has helpfully been digitised by the Public Records Office and all 61 pages are available free of charge online. The Inspector of Explosives, Cecil Hake had long experience with the CAC management trying to dodge the more onerous regulations of the explosives act. In 1890 the company even claimed that it couldn't abide by the Act because the women who worked there refused to wear the woollen serge dresses required and the Melbourne Punch published what can only be described as a grossly flippant comment on the situation when they said that "lovely woman is never more heroic than when she endangers her life to look pretty."

One of the key reasons for the explosion that comes through in the inquest files is just how little the women were trained in the functioning of the machines they used. None of the women were trained to maintain the machines and only rudimentary safety notices were made available and then largely ignored and this ignorance of the overall process and thus of the best practice safety precautions is a common theme in the history of women's employment in formerly male dominated occupations.

Women were usually introduced into an industry as soon as it was mechanised because this mechanisation allowed the work to be both better and broken down into small discrete processes, thus requiring less knowledge and training and therefore the possibility of less pay, and I discovered that this was explicitly stated by the company in my research in the National Archives of Melbourne records that are accessed through the Archive Centre reading room.

In the 1880s the colonial governments became concerned about the supply of small arms ammunition which had previously been shipped from the UK. In 1886 the Victorian Government quashed a suggestion by a British ammunition company to use Chinese labour to produce cheap ammunition on the basis that it would be, quote "extremely unpopular." The following year the New South Wales and Victorian Governments began negotiations with the CAC who had already set up a small arms ammunition factory in New Zealand. The New South Wales government lobbied for a place, not in Melbourne of course but a rural centre between the capitals, but the Victorian Government dismissed this by saying that in the event of a strike they wouldn't be able to replace the strikers i.e to find scabs and you have to remember that this was the time that Shearers Union had formed just the previous year and had already thousands of members. The CAC was keen to use female labour as they had done in New Zealand and they said that this was because paying men for the same work would leave them at a financial loss.

Footscray and its surrounds seemed to tick all the boxes - it was on a river that allowed safe transport of the ammunition and was close to centres of allied metal trades, also since the 1840s it had become home to many working-class families including of course women who sought work in the area, and historian John Lack quotes a newspaper at the time saying that it sent a glow through the ranks of servant-girlhood while it depressed Mrs Schild of the servants' registry and panicked local matrons.

So Footscray seemed to be the place to find white, female, unorganised labour. The CAC got two out of the three but almost from the outset the women set about organising to improve their relatively good but still meagre pay and conditions, and the first recorded indication of this happened just one year after work began.

In 1892 a deputation of women visited the Minister for Defence in protest at the lack of work because of a dispute with management about the applicability of the Explosives Act and the quality of the product. The Minister replied to the women that they should be happy to become domestic servants instead because at least then they'll be learning the skills needed once they were married and one newspaper reported that the reply came:

"Become domestic servants? No fear! We wouldn't be our own mistresses then nor knock off work at a fixed time."

It was also noticed in the reports that many of the women were bread winners for their families, contrary I think to a lot of the presumptions of the time, both then and now.

In 1895 the local health officer received a complaint about the working conditions of the factory and in the following year the Footscray independent received a letter from “a most disgusted employee” as she was called, which described a situation in which the women worked from 7:25 am to 5:15 pm with only two five-minute breaks and a lunch break. The disgusted employee may have possibly been Charlotte Crew, Alice White or Susan Gallagher who made up a deputation to the Victorian Trades Hall in December complaining of heat, poor wages and preferential treatment for some women. It was in that context that the explosion occurred and perhaps encouraged by the community responses we saw at the funeral, in December, just three months after the explosion, an open-air meeting was held on a vacant lot in Nicholson Street, Footscray. It was presided over by John Robert Davies. He was the local leader of the Knights of Labor and this was a sort of radical organisation somewhere between a union and a political party that began life in the United States.

Things went quiet for a few years but then in 1903 a reporter for the Independent newspaper wrote "the sight of a number of girls and young women playing cricket in the immediate vicinity of the Colonial Ammunition Company's works on Wednesday morning, at a time when they are usually busily engaged at work, indicated that something out of the ordinary was taking place. Inquiries elicited the information that the lasses had thrown down the implements of trade and were in the midst of a strike against the proposal to reduce the piece work rates for the making and packing of cartridges. Negotiations were entered into during the morning, the management gradually giving way until they reached one shilling two pence per thousand which they announced as the maximum they would pay and which the strikers, having concluded their cricket match decided to accept. So the strike ended and once more the employees of the company were working harmoniously together".

Now the reporter may have been too hasty in their assumption that harmony had been restored because the strike instantly became a cause celeb. By this time the Political Labor Council which is a local branch of what would become the Federal Australian Labor Party had taken over from the Knights of Labor as the main political organisation amongst workers around Footscray. They held a well-attended meeting at the Footscray Mechanics Institute at which prominent Labor politicians spoke and the women present voted to form a union. But it would take another 11 years for that union to come to fruition. Finally in 1913 the Ammunition and Cordite Workers’ Union was affiliated to Trades Hall and in 1915 it was registered federally. The union secretary was Richard Bell who was also the President of the Footscray branch of the Political Labor League. A membership register for the CAC works records 279 women members and quite a few male members as well. In 1918 the Footscray Union merged with the Small Arms Factory Employees and Workers Association to become the Arms, Explosives and Munition Workers’ Federation of Australia. The federal union was dominated by the male union leaders from the Lithgow small arms factory although it did have at least one female Victorian state president in 1930.

The formation of the union might have been spurred by an increasing number of employees at the factory as countries around the globe prepared for war. In World War One Australia didn't produce large munitions as they did in World War Two but the Footscray production was central to the Australian war effort. Every 303 cartridge used by the Australian army in the war was made by the women at CAC. The female workforce reached a peak of a thousand in 1916 and were given a prominent place in the annual Labor Day parade. In 1915 only 21 women marched in the parade but the following year 300 women marched under a banner reading "Australia defends itself".

The report from The Herald newspaper was nothing but effusive, "nothing could exceed the neatness of their appearance, the light swing of their movements, as they kept in time to the music of the band at the front, and their stride and enthusiasm for Empire and for Labour made their portion of the procession the showpiece of the day."

The Munition Workers Union and the women it represented I think really walked a delicate line in the debates around the war and conscription that rocked Australian politics during the war. Despite this seemingly sort of showy patriotism, anti-conscription activist Adela Pankhurst of the famous suffragist family was invited by the women to speak on the question during the factory lunch break at least once. At the peak of the war effort there was a lot of press interest in the factory and in the women who were often described as pioneer girls with the same sort of jovial tone that accompanies reports of women's work that seems to suggest there's something amusing about it, reinforcing I think the idea that women's work was worth less than men's.

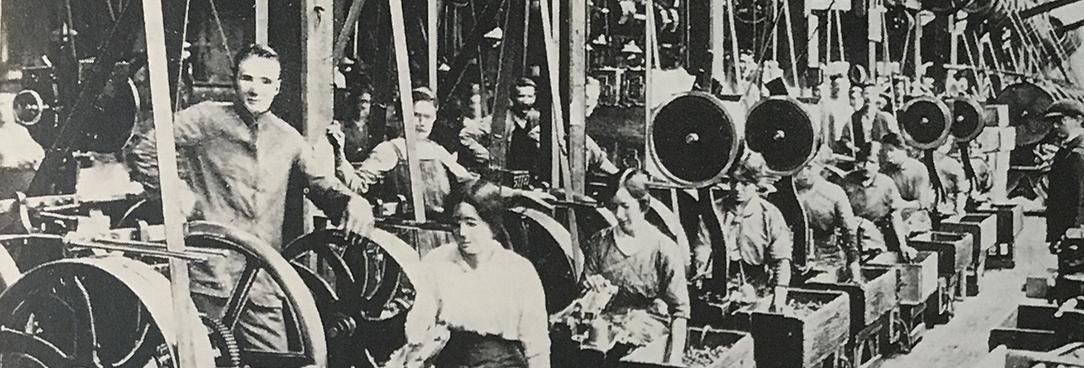

A full page report of a visit to the factory in 1916 read "they sit rows upon rows of them feeding machines fitted with revolving circular disks punched with small cavities. The noise is deafening but this does not seem to disturb the girls in the least and occasionally above the din one hears them trying to carry on a friendly conversation. One young girl rolling cylinders as if they were so many cigarettes, uses her left hand as deftly as her right. This small person looks very important manipulating huge revolving rollers, a piece of mechanism to be left in charge of which would cause terror to the average woman. A certain amount of nerve is necessary for women in charge of machines for by presence of mind in an emergency they can often avert serious financial loss. As they bent over their machines one could not help noting how well groomed their heads were."

But the sort of sparklingly patronising descriptions I think were part of an attitude that saw the women's livelihoods as merely supplementary and so by July 1917 as the allies were winning the war and government contracts for small arms ammunitions had begun to dry out, 700 women were laid off in one go. Conveniently, press reports also began to change their tone as more and more articles described with concern women who had taken liberty in their newfound independence they had won through their back-breaking and dangerous labour in the munition works in the UK and elsewhere and this was echoed in the Australian press. A mocking piece in the Benella Standard described the munition girl as "a heftier brawnier person never wore shoe leather" and The Herald inquired "the war has given us our flappers as we know them, can peace return us the schoolgirls as we would have them."

The union organised a protest meeting in which representatives pleaded that the women were often breadwinners, that their families relied on them and one spoke of the woman who made munitions her trade. The month after the mass sacking 100 of them met with the Prime Minister but he walked out on the meeting in an echo of something that would happen 100 years later. The union was isolated as the movement as a whole focused on the demands for jobs for returned servicemen. The plight of hundreds of recently sacked women was largely ignored. Further layoffs occurred in 1918 and the number of women working in the factory fell to 279. As the federal government increased its control over munitions production the CAC plunged into financial trouble. In 1921 it leased the works to the government. By 1923 there were only 37 women working at the factory. It would take another world war to bring them back.