Last updated:

‘Reading the Papers: the Victorian Lands Department’s influence on the occupation of the Otways under the nineteenth century land Acts’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 14, 2015. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Barbara Minchinton.

This is a peer reviewed article.

By the time Victoria’s Cape Otway Forest was opened up for settlement under the land selection Acts of the late nineteenth century, the Department of Crown Lands and Survey (colloquially known as ‘the Lands Department’) had had administrative control over land selection in the colony for about twenty years. Even though numerous land Acts had been enacted and amended by the Victorian parliament since 1860, and a Royal Commission in 1878–79 had examined the flawed outcomes of the 1869 Act, the land Acts of 1884 and 1890 proved to be a disaster for those who took up forest land in the Otways. Research on the nineteenth-century land Acts has largely focussed on the politics surrounding the legislation and the struggles of the selectors in poor country, rather than examining the role that the Lands Department’s administration played in the success or failure of the people on the land. How did the Lands Department respond to the mess unfolding in the Otways? A close examination of the department’s records shows that in the beginning it clung tightly to the letter of the legislation before gradually revising its decision-making to take account of the conditions encountered on the land. The papers held by Public Record Office Victoria reveal how and why the Lands Department came to ignore some central tenets of the legislation; they also expose the mechanisms used by the department’s officers to support those it regarded as bona fide land selectors.

Introduction

Arguments over the proper distribution of its Crown Lands began many years before the Colony of Victoria was created in 1851, and over the following decades the interests of wealthy squatters wanting to increase their pastoral holdings were pitted fiercely against those of the ex-miners and working men keen to make a home on a farm. The Nicholson Act of 1860[1] allowed the squatters to claim most of the available land. The Duffy Act of 1862 made things worse for the small-scale farmers, but even after the Grant Acts of 1865 and 1869 had effectively closed the legislative loopholes, it was common for bona fide land selectors to sell or abandon their allotments, allowing squatters to increase their already vast freehold pastoral estates, and a class of ‘boss cockies’ to arise among the selectors.[2] The results of the 1869 legislation were unsatisfactory enough to warrant a Royal Commission in 1878,[3] but still the push continued to make more land available for the yeomanry.[4] Unmapped forest country like that in the County of Polwarth south of Colac, however, was largely ignored; the terrain was too difficult and the forest cover too heavy for it to be attractive to selectors when easier land was still available. The Land Act 1884 was the last of the nineteenth-century land selection Acts to make large tracts of unallocated land available for small-scale farming, and it included what previously had been the Cape Otway State Forest. A substantial area of heavily timbered country (initially about 157,000 acres, or 63,535 hectares) was made available there before survey, without infrastructure (not even access tracks), and with inevitably high set-up costs given the need for extensive clearing. About a thousand selectors took up blocks of this Otway forest land in the last two decades of the nineteenth century.

Victoria’s Department of Crown Lands and Survey (known locally as ‘the Lands Department’) had been created in 1857, and was responsible for administering the land selection Acts; most of the Lands Department’s officers were located in Melbourne, over one hundred and sixty kilometres away from the Otways. The Local Land Board met at Colac to hear applications and matters relating to forfeiture, and initial enquiries and most follow-up questions could be dealt with by the Land Officer in Geelong (half-way between Melbourne and Colac), but neither the Land Officer in Geelong nor the members of the Land Board ever went to the forest.

The fundamental goal of the administrators in Melbourne was to facilitate ‘proper settlement’, as Assistant Surveyor JM Reed said in 1897.[5] ‘Proper settlement’, however, was a matter of judgement, not legislation, and most Lands Department decisions were judged on evidence supplied to its officers in writing on pre-printed forms. In this context, the archived records of the Lands Department resemble the Dutch colonial archives as described by Ann Laura Stoler, as being,

records of uncertainty and doubt in how people imagined they could and might make the rubrics of rule correspond to a changing imperial world. Not least they record anxious efforts to ‘catch up’ with what was emergent and ‘becoming’ in new colonial situations.[6]

Events in the Otway forest took place within a colonial setting, but the ‘emergent’ and ‘becoming’ elements in the forest situation had more to do with the natural environment than the political one. The Land Act 1884 was framed hard on the heels of the Mallee Pastoral Leases Act 1883,[7] and the landscape in the minds of the legislators and the bureaucrats appears to have been that of the dry, flat, red Mallee-rooted country, not the steep rainforests and deep brown mud of the Otways. When things started to go awry for the Otway selectors, it was no wonder the administrators struggled to understand – the picture in their heads did not match the ground the selectors were standing on.

Research on Victoria’s nineteenth-century land Acts has largely focussed on the politics surrounding the legislation and the disjunction between the yeoman ideal (which pervaded the debates surrounding land selection) and the reality of the selectors’ lives on the land.[8] While it has long been known that many selectors under the early Acts were allowed to carry arrears and aggregate family holdings in contravention of the legislation,[9] the extent to which the Lands Department actively supported the presence of resident selectors through deliberately lenient and flexible administration has not been explored. Regional histories, in fact, are far more likely to accuse the Lands Department of incompetence than to thank it for its assistance to selectors,[10] and tend to report the selectors’ trials and the letters they wrote begging government officials without including the supportive response.[11] Unfortunately in this respect Raymond Wright’s superb study of the Lands Department does not help to achieve balance; it was limited to the administration of public reserves, and did not include dealings between the Occupation Branch and the selectors.[12] The Occupation Branch’s archived records relating to the allocation of Crown land in the Otways, however, offer an opportunity (beginning in 1879) to trace changes to administrative practices, as the administrators slowly began to acknowledge the mistakes and misapprehensions built into both the land selection legislation and their procedures. Rather than recording a logical, linear progression of improvement via well-considered strategies, these records reveal a gradual seepage of evidence into the Lands Department, and a variety of responses to the rising tide of failure.[13] Denial and inflexibility were slowly replaced by helpless awareness and haphazard adjustments, as the selectors learned to employ the battering ram of petitions and deputations to the Minister of Lands to demand change and break down his department’s inertia. Administrative change, when it did come, was neither uniform nor clearly regulated. As a researcher it is not always possible to detect the point in time when changes began, or to locate the source of altered schemes of judgement. However, by surveying a great number of files and observing the patterns and timing within the file notes, and especially by unpacking the sometimes terse exchanges between the office and the field, and the Lands Department and its minister (often in the form of initialled marginalia), it is possible to piece together the Lands Department’s struggle to obtain ‘proper settlement’. This article shows how the administrators responded to the Otway challenge.

The papers

Each of Victoria’s land Acts were accompanied by a set of regulations which provided the framework for the Lands Department’s administration of the process of allocating land for occupation. These regulations had schedules appended which laid out the wording and format of the various prescribed documents and blank forms (such as applications). In addition, the Lands Department developed forms to standardise, for example, reports by Crown Lands Bailiffs, and applications for permission to ringbark.[14] The regulations, schedules and various forms relating to each land Act were applicable to all areas available for selection in Victoria, but under the Land Act 1884 land was divided into different classes with different rules (and paperwork) for each class; the vast majority of selectors applying for Otway forest land applied first for grazing leases under section 32 (henceforth, s32) of the Land Act 1884.[15] An s32 lease had no residence or cultivation requirements, it only required that the lessee enclose the land with a fence within three years and keep it free of ‘vermin’. At the same time, it demanded that the selectors not ringbark, destroy or cut down any timber upon the land without written approval from the Board of Land and Works. The Conservator of Forests (whose task was to conserve timber for commercial use, not for wilderness) ensured that such approval would not be forthcoming in the Otway forest for anything but ‘crooked or unsound timber’.[16] All ‘straight and sound’ timber was to remain untouched, despite it being impossible to make use of the timber commercially until railway transport became available in 1903. This combination of conditions rendered a lease useless to s32 selectors in most of the Otway forest, first because land could not be used for grazing without clearing the timber, and second because fencing was impracticable. The following sections will show how the Lands Department adapted the paperwork and decisions regarding these covenants in order to support those selectors it deemed to be bona fide.

Grazing Leases – ‘Permission to ring’

Numerous selectors wrote to the Lands Department pointing out the impossibility of grazing without clearing timber, and offering a solution:

The land is thickly covered with timber and scrub and quite destitute of grass and therefore unfit for grazing; in fact the land in its present state is quite useless. Under these circumstances therefore I would earnestly request that I may be allowed to clear fifty acres of the land … If permission is granted I would most zealously protect the most valuable timber and would not destroy the same indiscriminately.[17]

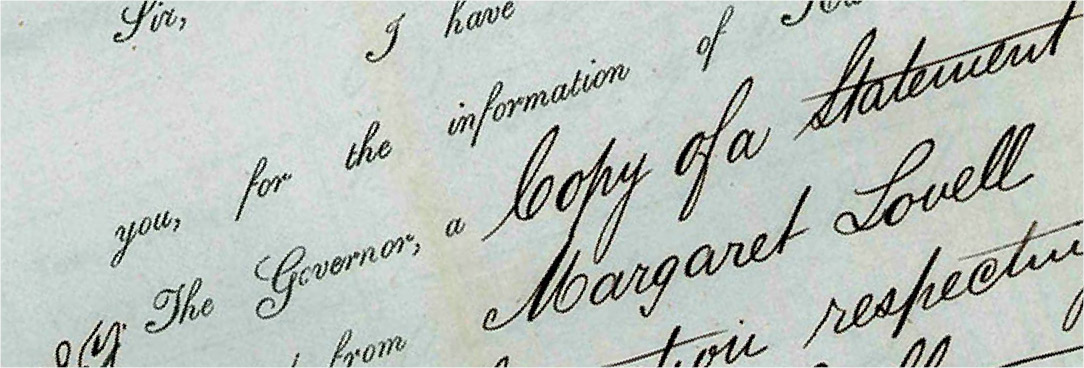

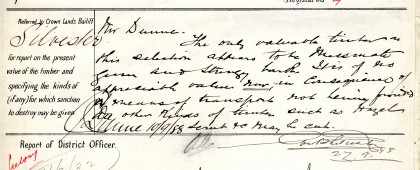

The Crown Lands Bailiff, who travelled around the forest and knew the conditions the selectors were encountering, agreed with them and told the Lands Department so:

The only valuable timber on this selection appears to be Messmate Gum & Stringy bark. It is of no appreciable value now, in consequence of means of transport not being provided – all other kinds of timber such as Hazel scrub &c may be cut.[18]

The underlining of the word ‘now’, however, was not the work of the bailiff. It was added later, apparently as justification for the Lands Department ignoring the bailiff’s recommendation and refusing permission to ring timber on William Murphy’s selection.

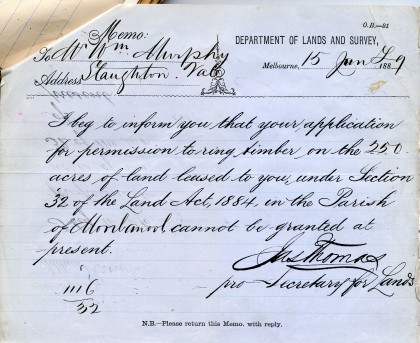

Requests for ‘permission to ring’ like the one from William Murphy were being received so often that the Department pre-printed a memo for the purpose of refusing them (see below).

However when William Murphy received this refusal he, like many other selectors, became irate:

I beg to bring under your notice the following facts 1st that there is no timber of any commercial value on my selection, 2nd that before the land can be improved all useless timber & scrub must be cut down and burnt, 3rd that in its present natural state the land is useless for any purpose. 4th that unless you give me permission to improve the land I can neither fence it nor reside on it. [19]

At this stage, though, the Lands Department was intransigent: rules were rules, and they stuck by them regardless of advice from their own bailiffs. An uncomprehending clerk in the Occupation Branch, James Thomas, responded to Murphy that ‘there is no objection to him cutting down the scrub, but the timber must not be ringed, or otherwise destroyed’.[20] He was presumably not familiar with the density of the timber cover frequently found in the Otways.

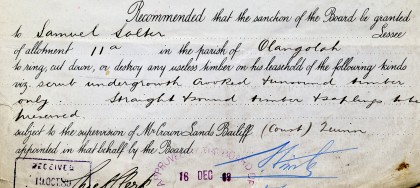

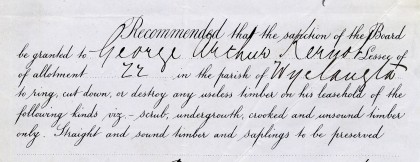

Later, when the sanction of the Board of Land and Works to ring timber wasgiven, it was often still of very little benefit to the selectors. Charles Finlayson, for example, was offered permission ‘to ring, cut down, or destroy’ useless timber on his selection at Weeaproinah between 3 May and 21 July 1892 – some of the wettest months in a year which had about 2000 mm of rainfall.[21] It was impossible to work in the forest under those conditions. Many of the sanctions that were offered by the Board of Land and Works during this period were of this type involving inappropriate brevity and timing. The major problem, however, was the definition of the timber that the selectors were given permission to ring. The process was controlled by a form that the Lands Department had printed in accordance with the Act. The sanction of the Board of Land and Works was granted ‘to ring, cut down, or destroy any useless timber … of the following kinds viz …’, with the blank to be completed by the Chief Clerk. He used a set of standard terms to specify exactly what was considered ‘useless’: ‘scrub undergrowth crooked & unsound timber only. Straight & sound timber & saplings to be preserved.’ At this point he did not recognise the uselessness of such ‘permission’ to the Otway selectors.

Selectors, however, knew it was nonsense. Many blocks were nothing but‘Straight & sound timber & saplings’. Some selectors reluctantly accepted the ruling and abandoned their selections in disgust,[22] while others ignored it and ringbarked anyway.[23] The majority of them simply waited for some resolution to the stalemate to appear, but a small number decided to fight it. A deputation met with the Secretary for Lands to point out the obvious difficulty, but also introduced another argument in favour of allowing lessees to ring and clear:

The present instruction as regards ringing is completely blocking the progress of settlement, and is also a great hardship to a number of Selectors who require to work a part of the year for others while clearing their own blocks. By removing the embargo against ringing, Capital would at once flow into the forest, and those Selectors whose labor is their only Capital, would be able to earn sufficient to enable them to improve their own holdings also.[24]

In terms of promoting the occupation of the land by small land holders it all made perfect sense, but the Lands Department did not choose to rethink its policy before the Land Act 1890 was published in July,[25] and the new Act continued the ban on ringing and clearing on s32 leaseholds. It also introduced a regulation which required selectors to report on their compliance with the covenants of their lease after three years.[26] For the earliest group of Land Act 1884 selectors in the Otways, the first of these reports was due to be submitted to the Lands Department in 1891.

Nehemiah Wimble had taken up the position of Secretary for Lands in April 1890,[27] but it was not until January 1891 that he acted on the selectors’ concerns. Rather than re-thinking the policy, Wimble chose instead to ask the bailiff to report on the compliance of the particular lessees involved in the deputation.[28] The selectors responded by putting together another deputation, no doubt aware that the new Minister of Lands, Allan McLean, had a Gippsland farming background and was likely to be sympathetic to their plight.[29] However much he turned out to be sympathetic, he was still unable to shift the secretary’s thinking. Wimble did recommend that the selectors be granted new leases with ‘permission to ring’ on the condition that they applied for agricultural allotments (that is, committed themselves to residence) within six months[30] – but the ‘permission to ring’ still only encompassed ‘useless’ timber, and usually for a limited time. Not only did the definitions of what could be cut or not cut remain the same, but the form was modified to save the Chief Clerk the trouble of writing out the same stock phrases (see image below).

But while the secretary evidently still did not understand, the clerk in the Occupation Branch who was responsible for the Otway selections, James Thomas, was beginning to do so. In January 1892, three years after he blithely told William Murphy that ‘the timber must not be ringed, or otherwise destroyed’, he was considerably more sympathetic to Charles Finlayson’s request for more time to complete his improvements: ‘I think the time asked for might under the circumstances and difficulties in dealing with this country, be allowed.’[31] Over the intervening years James Thomas had become a staunch supporter of those deemed bona fide selectors in the Otways, and had begun to stretch the rules to accommodate them. The issue of ringing was soon side-stepped by the selectors’ transfer to section 42 (residential) conditions, and then by the government’s acceptance of ringing on s32 leaseholds, but the Lands Department continued to help the selectors in relation to the fencing covenant.

Grazing Leases – fencing

The requirement to enclose the land with a fence within three years was continued under the Land Act 1890,[32] but as one surveyor described the Otways, ‘the country is covered with dense undergrowth of willow scrub & wire grass through which it is impossible to see or move a yard without cutting your way’.[33] In other places there was ‘not a blade of grass growing – nothing but a dense undergrowth of Ferns’[34] to the point where some selectors ‘could not even get around the boundery [sic]’,[35] while on Charles Finlayson’s block, there were ‘not 3 trees crooked or unsound to the acre, while there is say 40 sound ones good straight ones’.[36] There were also precipices, gullies and the occasional ‘small rock bound mountain torrent shut in by almost vertical walls of rock’[37] to contend with, making it

the height of absurdity to enclose the land in question with a fence… No person, except the surveyor, has ever been right round the land. It is three miles from a road, and the only means of access thereto is a bridle-track through dense scrub, and there has never been any trouble to keep cattle from coming out.[38]

One of the surveyors, in complaining of such problems when he tried to re-mark a previously surveyed block, also pointed out the solution:

Owing to the thick covering of wire grass which had overgrown the ground to a depth of several feet only a few of the ten chain pegs and trenches could be found … The others … will be found when the scrub is burned.[39]

In order to clear what was generally known as ‘scrub’, which could be anything from tree ferns and bracken to understorey plants such as hazel and musk or dense blackwood regrowth, selectors slashed and burned it. This certainly cleared the scrub, and enabled fences to be aligned and built, but the fires also often destroyed existing fences.

Selectors were caught in a cleft stick: they could not build fences unless the scrub was burned, but if the scrub was burned the chances were good that existing fences and other improvements would be lost in the process. Adding these difficulties together, it is not surprising that very few holdings were fully enclosed with a fence as required by the conditions of the s32 lease, in fact many of them had no fencing at all. But when selectors were required to report on their improvements, they were asked: ‘If the fencing covenant has not been complied with, by enclosing the land within the leasehold boundaries, state the reason why’.

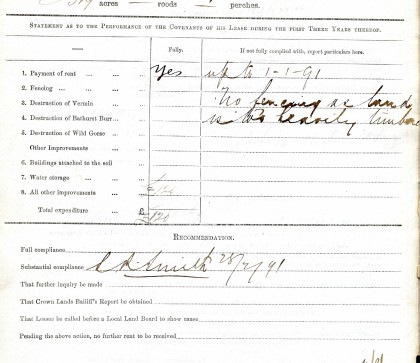

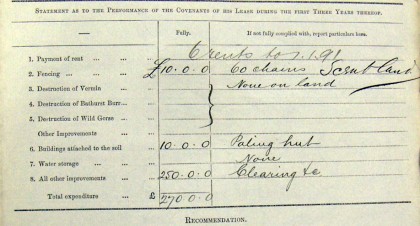

Selectors gave their reasons in varied terms: ‘Subject to Bush Fires by Burning Scrub’;[40] ‘Impossible to fence until cleared’;[41] ‘Fencing has been Erected but burnt. No use erecting New until country more opened up’.[42] And most telling of all: ‘scrub forms a sufficient fence’.[43] Yet despite the almost universal lack of compliance with the fencing covenant – or perhaps because of it – few of the selectors (if any) had their leases revoked over not meeting these requirements. Instead the Lands Department developed a standard they called ‘substantial compliance’. The term first appeared in the Otway paperwork on the Lands Department’s cover sheet for the ‘Statement of Lessee under Section 32 of the Land Act 1890 as to the Performance of the Covenants of his Lease’. The cover sheet provided a summary of the lessee’s improvements and expenditure, and a number of standard options for the Lands Department’s recommendation regarding the lease. The options included ‘full compliance’, ‘further inquiry’ and referral to the ‘Local Land Board to show cause’, each of which had a defined set of procedures to be followed, relating to issuing a lease, requesting a bailiff’s report or listing at a Local Land Board hearing. However, there was also the option of ‘substantial compliance’, which meant that the selector was known not to have fully complied with the conditions, but nevertheless the officer recommended continuation of the lease. It was effectively the same recommendation as ‘full compliance’, but it required an element of personal judgment from the Lands Department clerk who made the recommendation, because there were no set rules about what comprised ‘substantial’ as opposed to ‘full’ or ‘non’ compliance.

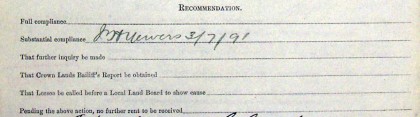

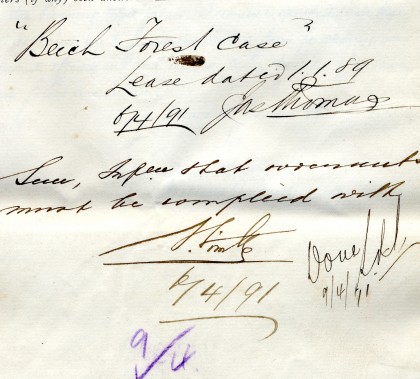

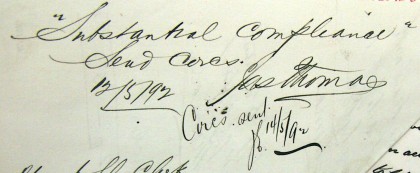

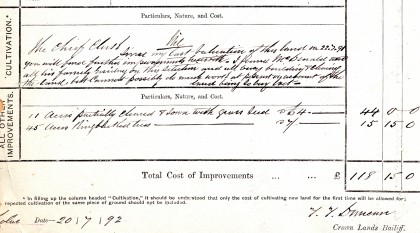

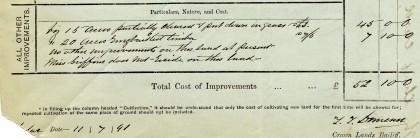

The cover sheet came into use in 1891 at the same time as the first selectors with s32 leases under the Land Act 1884 were required to report. In the early months of that year the officers of the Lands Department seemed uncertain about how to judge ‘substantial compliance’, and frequently referred files to the Secretary for Lands for a decision. The secretary tended to be strict, and inclined to ‘Inform that covenants must be complied with’ (see example below).[44]

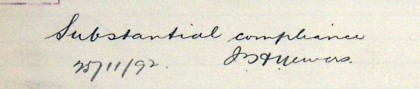

The clerks, however, tended to be more lenient: SR Smith, for example, recommended ‘substantial compliance’ in February 1891 when there were no fences on John Mulcahey’s land at all (see example below).[45]

Mulcahey’s case illustrates a number of the principles on which ‘substantial compliance’ was judged: first, his rents were paid up; second, his other improvements were substantial for that time (£120), and third, the clerk understood something about the country – it was he who added the explanation that there was ‘no fencing as land is too heavily timbered’.[46]

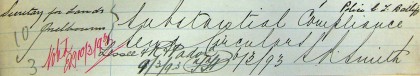

Gradually the other clerks, too, gained the confidence to accept minimal fencing when rent was paid up and other improvements were reasonable. A standard 320 acre block (half a square mile) would require 240 chains of fencing, but in June 1891 George Watson accepted only 10 chains of fencing because the land was ‘scrubby & subject to fires’.[47] By the middle of the year clerks working on the Otway selections were annotating cover sheets with ‘scrub land’ or ‘scrub country’ as explanation for insufficient or non-existent fencing (see example below).[48]

The term ‘substantial compliance’ gradually began appearing on other documents as well as the summary sheet (see examples below).

The category of ‘substantial compliance’ gave the Lands Department sufficient leeway to reward those selectors it deemed to be bona fide, but to weed out those who it believed were not. This, of course, carried the risk of favouritism and inconsistency. In August 1891, for example, the clerk JH Yewers called for a bailiff’s report for £125 of improvements without fencing,[49] yet in October recommended ‘substantial compliance’ for Alexander McDonald’s £80 of improvements with no fencing.[50] Clerks certainly had the capacity to act unfairly in this context, but the greater weight of evidence suggests that they used the category broadly to the advantage of most selectors.

Eventually the use of the category fundamentally scrapped one of the major covenants of the s32 lease (the requirement for fencing), but the terms of its use were under negotiation for some time. In October 1891, for example, the Chief Clerk recommended ‘substantial compliance’ for a lease which was part of a group family holding where the improvements were all on the other blocks, but the Minister of Lands over-ruled him.[51] In November 1892, however, when James Thomas asked the Chief Clerk: ‘Can we accept ringing only as substantial compliance?’[52] the Chief Clerk replied in the affirmative without reference to the minister at all.[53] By 1893 when the clerk WH Gregson informed the Chief Clerk that ‘There are no fences. Land is reported as scrubby’ on Thomas McMahon’s selection, the lack of fences was accepted without demur and the issue of his lease proceeded.[54] The Lands Department no longer adhered strictly to the legislation.

The Crown Lands Bailiffs[55]

In the early years of land allocation the Crown Lands Bailiffs had to find their way between the Lands Department’s legislative rock and the selectors’ hard place. The following section describes their efforts to help the selectors and facilitate the process of occupying the land.

Under the land Acts a bailiff’s report and valuation of improvements was required whenever a selector with a grazing lease applied for an agricultural allotment licence, or proceeded to an agricultural lease. They were also obtained if the Lands Department suspected non-compliance for any reason, or if a selector applied to transfer a holding, or wished to obtain a licence lien (a mortgage). Before the introduction of the regulation under the Land Act 1890requiring s32 selectors to report on their improvements, bailiff reports were rare, but the new regulation resulted in a kind of stock-take for the Crown Lands Bailiff GB Silvester. In May 1892 he had over seventy-five selections to check and report on ‘in the Beech Forest’, with more ‘coming to hand almost daily’. He was based at Morrison’s, south-east of Ballarat, and not especially familiar with the Otway forest, but his main concern initially was not the risk of getting lost:

In consequence of the late heavy rains the roads or rather tracks (for there are no roads) are in such a state as to be almost impassable. Mr Duncan who also has business in the forest advises papers to be held over until the roads improve … Immediately the roads are in a condition to travel on Mr Duncan and I have arranged for a simultaneous start.[56]

TT Duncan was the forester based at Colac, and before and after this stock-take period he conducted most of the bailiff’s work in the area – his ‘simultaneous start’ with Silvester was probably in order to show him where to go. Despite the dense forest and appalling tracks, Duncan knew his way about, although he was not infallible: ‘I beg to inform you,’ he wrote to the Lands Department on 21 October 1892, ‘that I inspected the wrong land on 4/8/92.’[57] This was a rare mistake for Duncan, unlike the Mounted Constables who reluctantly acted as Crown Lands Bailiffs. They frequently mistook one (unfenced) allotment for another: ‘The cause of the error in my previous report was owing to having no plans of district and my including the improvements of the adjoining block … there being no dividing fence’.[58]

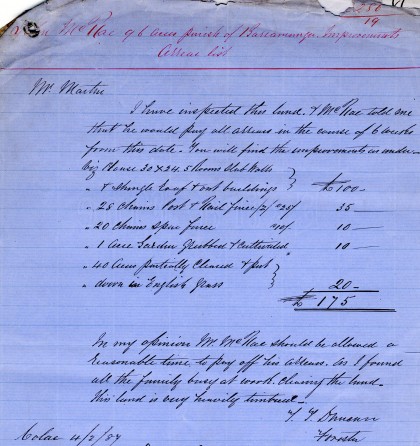

Duncan became one of the few Lands Department officers to have direct knowledge of the selectors and their situations. In his work he often struggled with the same conditions: ‘I am sorry to inform you,’ he reported to the Lands Department in August 1891, ‘that I was unable to cross the Gellibrand River until yesterday on account of the floods.’[59] From the beginning, his reports showed an understanding and sympathy for the selectors that was not initially found in the Melbourne office of the Lands Department. His early bailiff reports were written freehand, and inclined to be direct about his view that the selectors who were working hard should be shown leniency: ‘In my opinion Mr McRae should be allowed a reasonable time to pay off his arrears as I found all the family busily at work clearing the land. This land is very heavily timbered’.[60] But prior to 1891 the Lands Department’s response was usually cool: ‘Inform if portion of arrears is not paid in 21 days the Dept will have no alternative but to take steps to revoke the license and resume possession of the land’.[61]

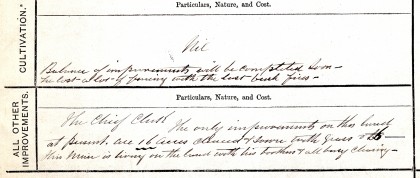

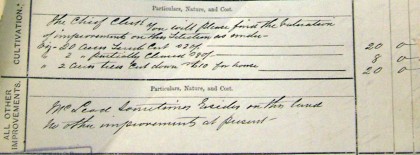

By 1891, though, the Lands Department had printed a standard form for the bailiffs to fill in. It had no space allocated for such comments, only for valuation of fences, destruction of vermin, value of buildings, water storage, cultivation and ‘all other improvements’. Rather than conforming to the shape of the form’s requirements, however, Duncan developed the habit of using the last two sections – ‘Cultivation’ and ‘All other improvements’ – as catch-alls for his comments, thereby continuing to give the Lands Department’s officers in Melbourne additional information on which to base their decisions about compliance. In this format he was less inclined to offer his opinion directly, but still likely to make statements which supported a selector’s bona fides: ‘Balance of improvements will be completed soon. He lost a lot of fencing with the last bush fires … This man is living on the land with his brothers & all busy clearing’ (see report below).[62]

‘I found McDonald and all his family residing on this selection & all busy building & clearing the land but cannot possibly do much work at present on account of the land being so very wet’ (see report below).[63]

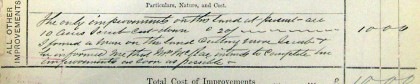

These later, more covert, pleas for leniency had a reasonable likelihood of success, as they fed and played into the Lands Department’s growing awareness of conditions in the forest under s32, and the clerks’ increasing use of the category ‘substantial compliance’. For example, Margaret McRae had done virtually nothing on her selection, and under ordinary circumstances would have been called upon to ‘show cause’ why her lease should not be forfeited, but Duncan added to his report ‘I found a man on the land cutting more scrub & he informed me that Mrs McRae intends to complete her improvements as soon as possible.’[64] She was not called upon to ‘show cause’.

The samples given above illustrate a common problem with the Crown Lands Bailiff’s report form. In Otway forest country the majority of the early work done on the land was clearing. Duncan recognised that there were many different phases of clearing, each associated with different time, labour and money costs, but the form did not acknowledge that complexity – clearing was not ‘fencing’, ‘building’ or ‘cultivation’, but at this stage it was more than simply an ‘other improvement’. Again, Duncan made the form suit his own purpose, which was to fairly represent the efforts of the selectors. First, he developed his own system of categorising the work done: for example ‘ringbarking’, ‘scrub cutting’ (or ‘scrubbing’), ‘partial clearing’, ‘tree cutting’, ‘grubbing’, ‘picking up’, ‘cultivation’ and ‘sowing grass seed’ were all listed independently. Then he developed a method for valuing each of the many combinations, according to the particular land being valued. So, for example, land ‘partially cleared & put down to grass’ might be worth £3 an acre or £4 depending on its location and type of vegetation cover; ringbarking might be 7/- or 7/6 or even up to 10/- per acre depending on the size and density of tree growth. ‘Scrub cut but not burned’ might be £1 per acre, but scrub ‘cleared, burned and picked up’ might be £3/10/- per acre. All of these categories he squeezed into the spaces for ‘Cultivation’ and ‘All other improvements’, along with any comments he wished to make (see examples below).

Duncan was not the only bailiff to use these classifications, of course, but he was the only bailiff in the Otways to develop such a detailed and consistent scheme, and adjust the paperwork to match. The Mounted Constables conducted far fewer inspections, and varied far more widely in their valuations,[65] which also tended to be less specific about stages of clearing. As one selector put it in the early 1900s, the mounted police were ‘not too perticular about going out of their way to do this extra work,’[66] probably because they already had plenty to do without travelling through rough country on an unwelcome and unfamiliar clerical errand.[67]

The difference between one bailiff’s valuations and another (there was no set scale) is one aspect of a larger problem with the Crown Lands Bailiffs’ reports which was both caused by and disguised by the forms themselves. The forms merely asked for ‘cost’ – of fences, of buildings, of cultivation and all other improvements – but it was never clear whether the ‘cost’ of improvements was to be based on the amount that the selector actually spent on them – the direct cost to the selector, including hours of labour – or on what they would have cost if they had been done at the time of valuation (in other words, whether it should be purchase or replacement cost). Some selectors clearly believed that the value of their improvements was determined by the receipts they held.[68] Others, like Charles Tucker (a resident selector), were clear that ‘value’ was not the same thing as ‘expenditure’: ‘I am well aware’, he wrote to Joseph Pettett (a non-resident selector), ‘that you have laid out a great deal more money on your selection than what I have valued your improvements at.’[69]

In practice the ‘cost’ given on the Crown Lands Bailiffs’ reports depended on the purpose of the form. If the report was to support the current lessee’s application for an agricultural licence or lease, and the bailiff believed the selector to be bona fide, the bailiff was inclined to value high (to help the selector). If it was post-forfeit then the bailiff might value low (to help the incoming selector who had to pay for them)[70] or high (to help the failed selector), or somewhere in between. There is some evidence of all of these scenarios, and also of valuations being somewhat haphazard. Adjustments were not uncommon; the Lands Department rarely refused a selector’s request for revaluation, and the result was usually an increase in the selector’s favour, not a reduction.[71]

The whole idea of the ‘cost’ of improvements was therefore somewhat fluid, especially since (as many selectors discovered) contracts cost more at some times of the year than others – ‘no one would undertake work in the forest during winter’[72] – but also less as the years went by and the country became more accessible. As William Jackson argued in 1897: ‘The scrub was cut on the ten acres referred to but that was five or six years ago … if I wanted that sort of work done today I could get it done for half the money that the last occupier paid for it’.[73] The discrepancy showed up most often – as it did for Jackson – when an incoming selector was asked to pay for improvements done by the previous lessee: should the bailiff value the improvements at the price the previous selector paid for them, or at the price the incoming selector could currently do them for? The Lands Department does not seem to have offered the bailiffs any guidance on the matter, leaving them to negotiate their own path through local obligations and the meaning of the forms, but after the early, strict demands made by Wimble as Secretary for Lands, his officials gradually became more and more lenient on those judged to be bona fide, at times going to extraordinary lengths to assist a selector to remain on the land.[74]

By 1894 the Lands Department had begun to actively seek the advice and assistance of Crown Lands Bailiff TT Duncan: ‘Are Lessees circumstances such that portion at least can not be paid now[?]’, a clerk asked.[75] Duncan’s reply, after consulting the selector, was that ‘he will try & pay the whole amount in about 4 months’. Duncan’s implied advice to accept the selector’s offer was heeded, and an extension of time to pay rents was given.[76] Duncan was probably trusted by the Lands Department officers at least partly because he was not an uncritical supporter of the selectors. A month after the previous note he advised the Land Officer of a number of lessees who he believed had not complied, saying ‘I am of opinion that these selectors should be challenged by the Dept as I think the most of them are merely holding on to their land for speculative purposes.’[77] His support was for the hard-working selectors, not the speculators, and the quality of his advice encouraged the officers in Melbourne to feel confident about doing likewise, thus bolstering the Lands Department’s promotion of small land holders at the expense of complying with the legislation.

Reading the paper trail

Sitting in the archives and picking up, for example, a selector’s application for a grazing lease in the Otway forest, it would be natural to read the document as part of a fixed system of administration, one element of the monolithic structure of nineteenth-century bureaucracy which underpinned colonial government. But the form itself, and the way the officers of the Lands Department chose to use it, can also provide insights into what Ann Laura Stoler has called the archive’s ‘restless realignments and readjustments of people and the beliefs to which they were tethered’.[78] The archives of the Lands Department provide evidence of a developing process being driven as much by attitudes as by the law. The Crown Lands Bailiff, for example, who ignored the structure of the report form in order to provide information supporting the hard-working selectors, was responding to his own belief in the superior value of hard work over capital. He asked for leniency for those who worked the land, not for the speculative investors. He did not judge the efficacy of the work done, or the appropriateness of the forest destruction wrought by the selectors. He judged the effort and intentions of the selectors, and made his judgement on the basis of their physical labour and that of their families. He believed that hard work should be rewarded.

The Lands Department officers, too, tended to support the selectors they judged to be bona fide, but they had a larger goal in mind: to spread farmers and their families right across the colony. The unaccommodating environment of the Otways provided a challenge to their belief that it was both desirable and possible to turn most of the colony’s land into small holdings for agriculture, so, while the bailiffs were encouraging the Lands Department to side-step the legislation for the sake of the individual selectors, the Lands Department wanted to reduce the failure rate and keep bona fide selectors on the land in order to maintain some semblance of what it regarded as ‘proper settlement’. The Lands Department clerks therefore used the information provided by the bailiffs, combined with their own category of ‘substantial compliance’, to determine which selectors to support in the face of almost total non-compliance with the covenants of the land Acts.

The Lands Department’s unspoken but absolute support for bona fide selectors – judged by the selectors’ intentions and hard labour – runs like bedrock beneath all of the archival records, and the influence of this attitude was far greater than that of the legislation itself. It was the willingness of the Lands Department officers to bend the rules, stretch the time limits and ignore the unworkable aspects of the legislation that enabled any of the nineteenth-century selectors to become owners of Otway land.

Endnotes

[1] For background and detailed information on Victoria’s Acts, see P Nelson and L Alves, Lands Guide: A guide to finding records of Crown land at Public Record Office Victoria, Public Record Office Victoria, North Melbourne, Vic., 2009.

[2] For a detailed summary of nineteenth-century land selection in Victoria up to the Acts of the 1880s, see JM Powell, The Public Lands of Australia Felix: Settlement and Land Appraisal in Victoria 1834–91 with Special Reference to the Western Plains, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1970.

[3] JM Powell (ed.), Yeomen and Bureaucrats: The Victorian Crown Lands Commission 1878–79, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1973.

[4] Regarding the driving ideal of the yeoman, see JM Powell, Mirrors of the New World: Images and Image-Makers in the Settlement Process, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1978, and Marilyn Lake, The Limits of Hope: Soldier settlement in Victoria 1915–38, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987, pp. 11–24.

[5] JM Reed, 2 June 1897, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0 Land Selection And Correspondence Files, Unit 225, 1251/42.44 Weeaproinah.

[6] Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2009, p. 4.

[7] The change to land leasing is discussed in JM Powell ‘The Land debates in Victoria, 1872–1884: Leases versus freeholds: A preparation for Henry George’,Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 56, No. 4, 1970, pp. 263–80.

[8] See especially the works of JM Powell.

[9] See P Grimshaw, C Fahey, S Janson and T Griffiths, ‘Families and selection in colonial Horsham’, in P Grimshaw, C McConville and E McEwen (eds), Families in Colonial Australia, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1985, pp. 118–137.

[10] For example, B Collett, Wednesdays closest to the full moon: A history of South Gippsland, Fernbank Publication Pty Ltd, Fish Creek, Victoria, 2009, p. 144.

[11] For example, J Murphy, On the Ridge: The Shire of Mirboo 1894–1994, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 1994, pp. 21–38.

[12] R Wright, The bureaucrats’ domain: Space and the public interest in Victoria 1836–1884, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1989.

[13] For statistics and analysis of the failure rates in Otway land selection, see B Minchinton, ‘“That place”: Nineteenth century land selection in the Otways, Victoria, Australia’, PhD, University of Melbourne, 2011.

[14] ‘Ringbarking’ was the process by which large trees were killed in preparation for burning to clear the land.

[15] B Minchinton, ‘The Trouble with Otway Maps: Taking up a selection under Land Act 1884’, Provenance, 10, 2011, available at <http://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2011/trouble-otway-maps>, accessed 20 August 2015.

[16] N Wimble summary for Minister, 30 October 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5839, 2399/50.51 Olangolah.

[17] Ibid., 10 October 1889.

[18] GB Silvester, 27 September 1888, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5851, 2554/42 Moorbanool.

[19] William Murphy, 22 January 1889, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5851, 2554/42 Moorbanool.

[20] James Thomas, 25 January 1889, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5851, 2554/42 Moorbanool.

[21] ‘Application for Permission to destroy timber’, 3 May 1892, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5854, 2752/42.44 Weeaproinah; Royal Commission on state forests and timber reserves, Fifth Progress Report, Appendix 1, 1899–1900, p. 15.

[22] James Hendy, 7 December 1891, PROV, VPRS 440/P0 Land Selection and Occupation Files, Unit 1208, 761/32 Wyelangta.

[23] Crown Lands Bailiff report, 14 August 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5841, 2613/42.44 Moorbanool.

[24] Charles Craike, 23 August 1890, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5839, 2399/50.51 Olangolah.

[25] Victoria Government Gazette, No. 59, 11 July 1890, p. 2836.

[26] Victoria Government Gazette, No. 77, 5 September 1890, p. 3561, Regulation V (s8) Schedule X: ‘Statement of lessee under Section 32 of theLand Act 1890 as to the performance of the covenants of his lease’.

[27] Victoria Government Gazette, No. 39, 2 May 1890, p. 1595.

[28] Memo N Wimble, 29 January 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5839, 2399/50.51 Olangolah.

[29] Allan McLean (1839–1911), biography available at <http://www.maffra.net.au/heritage/hisfed.htm>, accessed 14 June 2010.

[30] Memo N Wimble, 30 October 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5839, 2399/50.51 Olangolah, marked ‘Approved AML 30/10/91’.

[31] James Thomas, 20 January 1892, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5854, 2752/42.44 Weeaproinah.

[32] Section 38 (7) Land Act 1884 and Section 38 (7) Land Act 1890.

[33] G Cornthwaite, 1 December 1903, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 298, 248/44 Barwongemoong.

[34] Charles Craike, 23 August 1890, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5839, 2399/50.51 Olangolah.

[35] Samuel Salter, 2 January 1892, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5552, 2233/42.44 Olangolah

[36] Charles Finlayson, 5 August 1892, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5854, 2752/42.44 Weeaproinah.

[37] James Short, 9 June 1900, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 247, 259/47 Barwongemoong.

[38] Richard Griffiths, 20 April 1903, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 292, 212/47 Olangolah.

[39] James Short, 10 December 1894, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 212, 1432/42.44 Olangolah.

[40] Thomas Butler, PROV, VPRS 440/P0, Unit 1219, 117/42 Weeaproinah.

[41] Ann Briers, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 275, 1952/J Weeaproinah.

[42] Edward Hall, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 297, 155/13 Olangolah.

[43] William Thompson, 9 July 1897, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5587, 1802/42.44 Olangolah.

[44] N Wimble, 6 April 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5547, 5481/47 Moorbanool; see also N Wimble, 4 April 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 374, 1683/42.44 Barramunga.

[45] Statement of Performance cover sheet, 20 February 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5545, 2798/42.44 Weeaproinah.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Statement of Performance cover sheet, 5 June 1891, PROV, VPRS 5714/P0 Land Selection Files, Section 12 Closer Settlement Act 1938 [including obsolete and top numbered Closer Settlement and WW1 Discharged Soldier Settlement files], Unit 218, 417/12 Weeaproinah.

[48] They continued to do so: 9 July 1897, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5587, 1802/42.44 Olangolah; 13 April 1899, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 231, 1086/42.44 Weeaproinah.

[49] JH Yewers, 11 August 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5554, 2774/42.44 Wyelangta.

[50] Statement of Performance cover sheet, 13 October 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5894, 227/50 Weeaproinah.

[51] N Wimble to JJ Blundell, 27 November 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5555, 2645/42.44 Weeaproinah,

[52] James Thomas, 11 November 1892, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 360, 2017/49.50 Wyelangta.

[53] Chief Clerk, 11 November 1892, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 360, 2017/49.50 Wyelangta.

[54] File note WH Gregson, 19 September 1893, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5851, 2565/42 Moorbanool.

[55] For the first ten years of land admininstration the Crown Lands Bailiff for the area was located at Morrison’s, south-east of Ballarat, but the forester located at Colac fulfilled most of the bailiff’s duties, supplemented by Mounted Police located at Krambruk (Apollo Bay), Colac and Port Campbell.

[56] Crown Lands Bailiff, 16 May 1892, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5567, 2481/49.50 Olangolah.

[57] TT Duncan, 21 October 1892, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5869, 510/46.81 Moorbanool.

[58] Constable J McCallum, 19 October 1897, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5562, 2139/42.44 Aire.

[59] TT Duncan, 26 August 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 303, 1262/42.44 Barramunga.

[60] TT Duncan, 4 February 1887, PROV, VPRS 626/P0 Land Selection Files by Land District, Sections 19 and 20 Land Act 1869, Unit 958, 2286/19.20 Barramunga.

[61] N Wimble, 16 February 1887, PROV, VPRS 626/P0, Unit 958, 2286/19.20 Barramunga.

[62] TT Duncan, 12 May 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5856, 2624/49.50 Weeaproinah.

[63] TT Duncan, 20 July 1892, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5856, 2623/42.44 Moorbanool.

[64] TT Duncan, 2 November 1892, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5557, 2302/42 Weeaproinah.

[65] Correction of his own valuation by Police Crown Lands Bailiff Olney, 27 April 1909, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5856, 2624/49.50 Weeaproinah.

[66] C Tucker to Joseph Pettett, 29 August 1906, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5554, 2770/49.50 Weeaproinah.

[67] JG Sainsbury, 12 March 1903, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 292, 212/47; MC Olney, 25 February 1906, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5838, 2111/49.50 Barwongemoong.

[68] William Cavanagh, 25 March 1905, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 298, 2168/49.50 Wyelangta; Thomas Alcorn, 16 June 1894, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5800, 376/44 Moorbanool.

[69] C Tucker to Joseph Pettett, 29 August 1906, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5554, 2770/49.50 Weeaproinah.

[70] James Short, 13 January 1900, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 296, 2439/42 Weeaproinah.

[71] PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5588, 1885/42.44 Moorbanool.

[72] T Murphy to WT Webb MP, 3 October 1891, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5851, 2565/42 Moorbanool.

[73] William Jackson, 5 October 1897, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5837, 2442/42.44 Olangolah.

[74] For example Charles Trew, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 3248, 1846/49.50 Barwongemoong; Bridget Cullen, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5562, 2143/42.44 Moorbanool.

[75] File note WH Gregson to Crown Lands Bailiff, 8 February 1894, PROV, VPRS 626/P0, Unit 958, 2286/10.20 Barramunga.

[76] File note TT Duncan, 6 March 1894, PROV, VPRS 626/P0, Unit 958, 2286/10.20 Barramunga.

[77] Memo TT Duncan, 6 April 1894, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5839, 2392/42.44 Olangolah; see also Memo TT Duncan, 17 April 1894, PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 5800, 376/44 Moorbanool.

[78] Stoler, Archival Grain, pp. 32–33.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples