Last updated:

‘Preparation for Death: the story of Francis O’Brien, Mildura High School Headmaster and family annihilator’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 13, 2014. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Lee Hooper

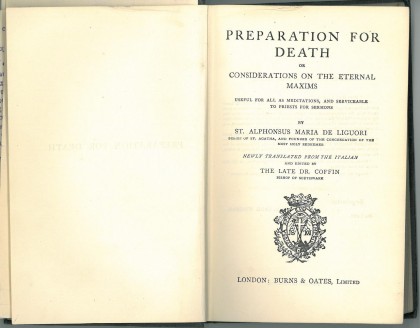

On 28 May 1934, Francis O’Brien (Frank) slit the throats of his wife, three children and then himself. Discovered close to Frank’s body was a small black book entitled Preparation for Death, edited and translated by Dr Coffin. It was a premeditated murder–suicide.

Upon investigation into the circumstances surrounding the familicide, police discovered that this was the same Francis O’Brien who killed his wife with a hammer 10 years previous while he was Headmaster at Mildura High School.

How did the system fail Frank and his family? What are the conditions surrounding both murders and what was Frank’s state of mind really like? Using records from Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) this article explores Frank’s life and the events surrounding both murder cases; it takes a look at the mental health and crime prevention processes that were in place at the time, and examines how such a horrendous tragedy was able to occur in the first place.

Definition of familicide

A familicide is a multiple-victim homicide incident in which the killer’s spouse and one or more children are slain … Familicides were almost exclusively perpetrated by men, unlike other spouse-killings and other filicides. Half the familicidal men killed themselves as well …[1]

A family massacre

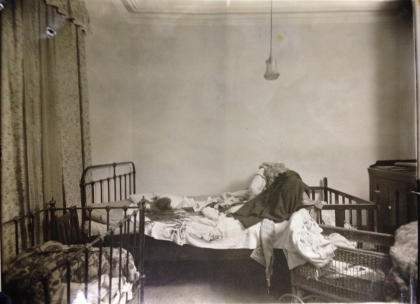

On 30 May 1934 the bodies of the O’Brien family were found dead in their beds. Father, Francis (Frank), 59 years, wharf labourer; Mother, Rose, 39 years, home duties; Son, Owen Francis, 3 years and daughters Joan and Marie, 2 years and 11 months respectively. Each member of the family had their throats cut, with the children also sustaining head wounds.

There was little doubt that the deceased Frank O’Brien killed his family and then himself. His hands were covered in blood and an open and bloody razor lay beside him.

A prayer book, Preparation for Death was found in the bedroom with the bodies and a partial note on the living room mantle told a story of a desperate and sick man worried about finances and the future.

For months my health has been going off. I began to lose interest in everything since coming to this hovel with no conveniences, no copper, no washing troughs, not even a decent bath, and a lavatory that won’t flush properly, not even an oven or a stove to cook. Dear, patient, unselfish Rose, always cheerful and self-sacrificing, has tried to keep a smiling face in spite of bad times. She has been a hundred percent wife and mother, and deserves the best in life. I can see the strain is telling on her as it is on me, trying to make ends meet.

My appetite has completely gone. Constipation has got me in its grip, and now the demon insomnia has claimed me. For weeks I have been losing weight. I have lost between 1 ½ and 2 stone since coming here and am fast becoming a physical and mental wreck.

I am afraid of the future. I soon will not be able to continue work and you know what that means to them all. I tried to keep going but life lately has been a living hell. Rose would rather starve than be in debt and yet at times we could not avoid it. Come to see me as soon as you can as I want your advice and to explain …[2]

The police also found a number of horse racing systems in each room of the house, as well as a book entitled Betting to Win. The meticulously kept systems speak of a man desperate to alleviate financial hardship, seemingly without success.

This devastating tragedy was not expected by any of those close to the O’Brien family, who claimed Frank was very attached to his wife and had great affection for his family. But upon further investigation, evidence showed it certainly could have been predicted.

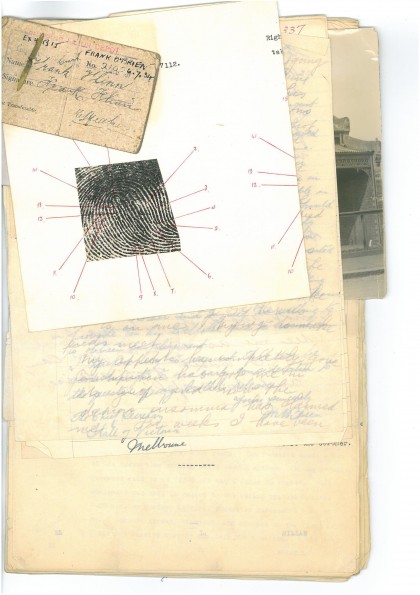

Upon making enquiries into Frank’s past, the detective in charge of the investigation Leo McKenna, discovered a devastating reality. Ten years earlier Francis O’Brien had been charged with the murder of his then wife, Clara O’Brien, who he battered with a hammer as she lay sleeping in her bed.[3] Frank claimed to have not remembered the act and a judge subsequently found he was not guilty due to ‘confusional insanity’[4] and was committed to Mont Park Hospital for the Insane.

But did the system also have blood on its hands? Frank was a man stifled by dwindling health, a gambling addiction, a secret prior murder conviction and a fearful uncertainty about the future. However, he was also a doting father, a loving husband, and a well-regarded friend who by all accounts gave the world the face of an everyman, struggling through the Great Depression but trying to do the right thing. How is it that the authorities could fail a man with such an unpredictable previous mental health problem? No doubt a lack of understanding surrounding mental illness by the authorities responsible at the time and a deficiency in probationary laws were contributing factors which in combination in Frank’s case led to a failure to prevent the familicide. So where does the blame lie, with the state authorities or the man?

This article will examine Frank’s mental health history and how these horrific murders came to pass. The article draws on information in the criminal trial brief relating to the murder of Clara O’Brien and the inquest into the O’Brien family massacre. We will also delve into the discrepancies surrounding the support and supervision provided to Frank by the Victorian Law Department and the Victorian Lunacy Department after he was released from Mont Park in 1927 and will discuss how Frank fell through the cracks of a system that was not equipped to help or protect him or his family, resulting in horrific consequences – family annihilation.

Francis O’Brien – Headmaster

Francis O’Brien was born on 20 July 1875 at Campbells Creek, Victoria to Michael and Ann O’Brien. Frank had at least five siblings and according to the original criminal trial brief into Clara O’Brien’s murder, two of Frank’s sisters were ‘slightly mentally affected’[5] and one brother, Jack was sent to Royal Park Mental Hospital for treatment when he was younger.

Frank left home at 19 years-of-age and became a school teacher. This was a career that would span almost 30 years, seeing him rise through the levels of teaching until he was honoured with the position of Headmaster of Mildura High School in 1921.[6]

In 1905 Frank met and married Clara Ellen Hill, three years his junior. They were considered a happy couple and went on to have six children during their time together; Charles, Francis, John, Isabella, George and a baby born in 1924 (name unknown). They were by all accounts a very happy family.

As the years went by, Frank became increasingly nervy, sick and anxious. It was towards the later stage of his career that he started to have mental breakdowns.

According to statements taken in the criminal trial brief for Clara’s murder, some time in May 1918, when Frank was stationed at Rutherglen State School as Head Teacher, he was apprehended for taking an axe and smashing up the brick building of the school. At this time he was taken to the police station, medically examined and subsequently sent to the receiving house at Royal Park, Melbourne. Frank was examined there by Dr Godfrey (who would later be the examining doctor in Clara’s murder trial). Frank was kept under Godrey’s care for a few weeks and when released took a leave of absence from teaching until September 1918.

Frank resumed duty on 9 September 1918 as an assistant teacher at a school in Footscray where he remained until he was appointed Headmaster at Mildura High School on 1 September 1921.

According to Frank’s teaching records, his performance of duties was excellent at Mildura until late July 1922 when he had a nervous breakdown and had to take time off. Frank went back to work in August and time passed without incident until 18 October 1922 when Mildura High School was set alight.

Frank was nowhere to be found.[7]

As the school burned, the authorities and fellow teachers wondered about Frank’s safety. As events turned out, at 8:45 am that morning Frank was already at the Mildura watch house. Constable Richard Bonnsel came across Frank there, sitting, twitching and dazed. The constable approached him and asked him how he was and when he did not answer the constable sat beside him. Eventually Frank asked ‘You want to see me?’ and when the constable in return asked him why, Frank answered ‘about the fire’. At this point, the constable did not know about the fire and tried to get Frank to speak again but he remained silent, his eyes dazed. By all accounts he appeared to be a ‘hopeless imbecile’ and did not understand any remark spoken to him.[8]

It is interesting that the criminal trial brief into Clara’s murder and Frank’s education department records all point to Frank being missing at the time of the Mildura fire, before he voluntarily turned up at the police station but acting guilty and unco-operative. Constable Bonnsel claimed he removed a knife from Frank’s pocket and detained him. It would seem that there were definite suspicions that Frank was involved in the arson, though he never admitted it. A full report of the incident was made but no charges were ever laid.[9]

Frank was hospitalised after the fire at Mildura High School. He was off work for two months. Education records stated that his medical certificate for this time off showed he was suffering from ‘extreme physical and mental depression’.[10]

Frank went back to work in December 1922 but it seemed he had not as yet fully recovered. In a letter to the Working Man’s Club in Mildura dated 16 January 1923 Frank tells a story of being unhappy with his position at Mildura and seeking a new position in a metropolitan area. Frank wrote:

I do not know what is wrong with me, but since September I have been gradually going down hill. Physical exertion and mental work are alike an unendurable burden on me. I do not feel fit for anything at all. I thought at first that a good rest during the Christmas vacation might fix me up but it has not done so, so far …[11]

He continued saying that he had no interest in life and was concerned about bringing ruin and misery to his family. He then asked for help:

My sleep, too, is disturbed with awful dreams and nightmares. I sometimes wonder if my mind is permanently going, and my brain diseased. I have tried to hide my suffering and my illness from my family so as not to worry my wife. I write this to you … so that you will understand why it may be best for me to get a transfer in the New Year even though we will have to pay our own expenses …[12]

This letter was a distinct call for help, showing a man on the periphery of a complete mental and physical breakdown. And yet no response was given. He went back to work at Mildura High School and even took on additional teaching duties.

According to a statement given by Frank’s son, Charles, around September 1923 he became unwell again, often keeping to himself. Towards the end of the year he appeared to become even worse, staying in bed and becoming progressively moodier and worried.

Frank was clearly a man on the edge. But no one expected he would be capable of killing his beloved wife.

‘What have I done?’

At 6:00 am on Saturday 26 January 1924, Frank’s 17-year-old son Charles got out of bed. He was supposed to work that day and went to wake his father. Frank told him to ‘go back to bed until I get things ready and I will call you in a few minutes.’[13]

Charles went back to bed. His bedroom was in the room adjoining his parent’s bedroom. As he lay there he heard his father moving about in the kitchen, thinking that he was making breakfast preparations. Charles heard what sounded like a couple of blows or a banging noise that sounded like it was coming from his parent’s bedroom.

A few seconds later his bedroom door opened and Frank rushed at Charles. He had a hammer in his hands and he tried to strike his son. Still in his bed, Charles struggled with his father yelling at him to stop. Frank had a strange look in his eyes and was obviously not himself.

After a time of struggle Frank suddenly stopped, grasped his head and said ‘What have I done now.’ All of the other O’Brien children slept through the altercation.

Charles went into his parent’s room and discovered his mother in an unconscious state, her skull broken and bloody. Removing the 8 week old baby from the room Charles rushed down the road to get Dr Brown.

What followed would have been considered a fairly primitive investigation in modern terms, but for the O’Brien family it was an assault of doctors, ambulance men and police officers. When approached by police officers, Frank asked ‘what is wrong Sergeant’, and said ‘I feel as if I am in a nightmare.’[14] Dr Brown examined Clara and realised by the damage and amount of blood on the pillow that her situation was dire. Frank was not restrained at this point, but left alone at the kitchen table in his apparent ‘mentally affected’ state.[15]

The dealings of the crime scene were nothing like what we’re used to seeing on television crime shows, where the vicinity would be immediately quarantined, the room sifted top-to-bottom for clues and blood-splatter analysis, the weapon isolated, bagged and tagged. There was no crime scene photographer on hand, documenting every inch of the house, nor any family psychologist able to deal with hysterical children. The suspect was neither restrained nor read his rights.

Responsibility for the five younger children, including the eight week old baby boy, fell to 17-year-old Charles. Frank was also allowed to change his clothes and the weapon was haphazardly seized by an officer from atop the fridge. Photographs were not a thought. Compared to what we are accustomed to nowadays, it seemed a fairly casual process.

Frank was taken to the Mildura police station. When the charge of grievous bodily harm was read to him he exclaimed ‘What! My wife, my wife’.[16] It was apparent Frank’s ‘confusional insanity’ had struck again.[17]

Clara was taken to Mildura Hospital where she was operated on, but died 4 days later from a fractured skull and lacerated brain. This development changed O’Brien’s grievous bodily harm charge to that of wilful murder.

The King v Frank O’Brien

An investigation began and Frank went on trial at the Supreme Court, Castlemaine on 11 March 1924.

Various witnesses stepped forward to vouch for the decent character of Frank O’Brien. Police officers and doctors brought to light his previous amnesiac mental breaks. And yet they all agreed that they did not expect it from the family man. Did the fact that Frank held a high-ranking position as a school headmaster cloud the judgement of those around him, even though he had a concerning history with mental illness sometimes resulting in destruction? It would be expected these days that if an individual was hospitalised multiple times due to nervous breakdowns, extreme depression and particularly amnesiac destructive or violent episodes that they would be monitored regularly by a health care professional and potentially medicated. No doubt the lack of advances and understanding in the mental health profession in the 1920s was a factor in Frank’s case. Frank’s mental illness was also very unpredictable, and it’s hard to imagine that the tragedy could have been prevented under the prevailing circumstances.

In his statement at the trial, his son Charles stated:

Our family life was a happy one and my father and mother were devoted to each other … My father was of very temperate habits. I had never known him to attack any member of the family previous to this …[18]

Constable Shankly gave a statement of arriving at the O’Brien household on the morning of the incident, finding Clara close to death and the normally personable O’Brien in a confused mental state.

Dr Joel Brown gave a statement of attending to Clara at the house that morning and the mental state in which he found Frank. Dr Brown gave an account of the previous times he had examined Frank while being mentally affected. It was his opinion that Frank was not capable of appreciating what he was doing and that the ‘disease as exhibited by Frank was very elusive from his point of view.’[19]

Government medical officer Dr Godfrey gave his statement in relation to examining Frank in Melbourne Goal in early February 1924. He mentioned that O’Brien was under his care from 1918 after the axe incident at Rutherford School. Dr Godfrey diagnosed Frank with ‘confusional insanity – the climax of a condition of psychasthenia associated with an inherent mental instability’.[20] He stated that at the time of the examination Frank was in a normal mental state but at the time of the tragedy he was in suffering from a ‘state of mental unsoundness’.[21] He concluded:

I consider from definite disease of the mind he was incapable of knowing that he was killing his wife or any human being or of realising what he was doing …[22]

On 11 March 1924 a verdict of not guilty on the grounds of insanity was given. On 20 March 1924, Frank was admitted to Mont Park, in Macleod, Victoria.

Becoming Flinn

Frank became a model patient at Mont Park and using his previous educational experience was put in charge of the library and employed in the telephone room. It was reported that his mental state remained stable and showed no variation during the time he was a patient.

On 9 September 1924 Dr John Catarinich reported of Frank:

At present and has been since admission here, sane. There is, however, present a lack of emotional reaction, which to some extent may be due to no conscious memory of the crime committed.

The history submitted with his case shows that he has had more than one attack of insanity, and he is, therefore, very likely to relapse.

Under no circumstances would I suggest O’Brien ever again living [sic] with his children, nor do I consider it safe to give O’Brien his liberty, even with restrictions. Supervision of someone with a skilled knowledge of insanity would not guarantee that O’Brien’s impulses could be foreseen.

I therefore cannot make any favourable recommendation for him.[23]

Regardless of Catarinich’s report, over the next three years O’Brien filed various petitions to his Excellency the Governor seeking his release. All appeals were denied as per Catarinich’s initial recommendation.

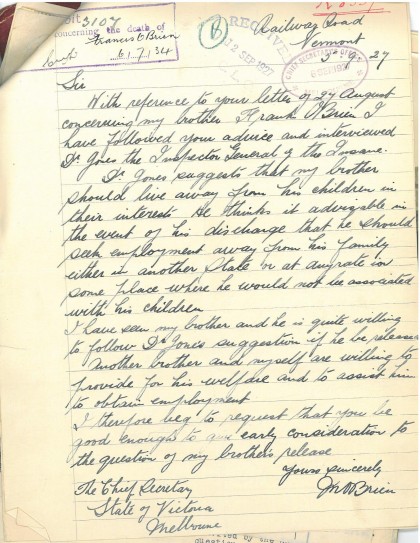

In August 1927 O’Brien’s brother, Michael, wrote to the Chief Secretary, requesting the release of Frank from Mont Park. Although this request was denied, the Director of Mental Hygiene Dr Jones replied that after three years of observing Frank he was now of the opinion that Frank was sane and if some person would undertake the responsibility of providing for Frank’s future welfare, his release might reasonably be granted.

It was pointed out by Dr Jones that the Lunacy Act 1903 did not have clauses that directly governed how criminal lunatics could be released under a probationary or parole period, only for trial leave. In comparison to parole this was a much more relaxed situation, requiring patients to check in and be evaluated as long as the Lunacy Department considered necessary. In fact, they did not have any way of dealing with a probationary release under any conditions. In the early 1900s the notion of criminal probation and parole obligations was solely a Law Department responsibility and as Frank was under the care of the Lunacy Department, probation or parole laws did not directly apply to him.

As far as Dr Jones and the Lunacy Department were concerned, if Frank was to be released from Mont Park, he would have to be completely discharged.

Michael O’Brien replied on 5 September 1927 that both himself and another brother would be willing to provide for Frank’s welfare and would assist him to obtain employment.

Frank was released into his brother’s care by the Governor under the Crimes Act 1926 on 28 November 1927, just three years and eight months after his incarceration. He was released with the proviso that:

- He did not live with his children,

- He reported every month, either to the Inspector General or the Superintendent for examination of his mental condition, and

- He did not resume his departmental duties.[24]

Frank followed these instructions regularly for a period of time, voluntarily reporting to the Lunacy Department on a monthly basis, but gradually began to drop off in his reports. As the department did not have an official reporting system in place for those released on a trial basis, they had no adequate way of cementing a structured and enforced reporting schedule with Frank. It seemed they relied solely on Frank to approach them of his own free will and there was no documentation that they were ever overly concerned when his reporting started to drop off in frequency. By 1930 Frank was only reporting to Dr Jones every three months or so. Dr Jones stated during the inquest into the familicide of 1934 that he did not make any real attempt to chase Frank directly, believing he had no power under the Lunacy Act 1903 to do so as essentially Frank was released under the Crimes Act 1926, of which Dr Jones had no real understanding. He also admitted that he was not even certain how often Frank reported, or of his condition on those dates as he did not keep notes regularly. Dr Jones stated that from late 1930 Frank did not make any further reports.

The confusion surrounding Frank’s release under the Crimes Act 1926 and the disorganised and undisciplined way in which Frank’s release into the community was carried out is staggering by today’s standards. How could anyone have expected to monitor his mental state? Where did the responsibility of duty of care end in such an unorthodox situation? Dr Jones himself stated that the situation itself was a very unusual one and he tended to put the underlying responsibility onto Frank’s relatives who agreed to care for him.[25]

In 1929, Frank moved to Melbourne where he married Rose Love. It is claimed that he met Rose while a patient at Mont Park. Rose and Frank would go on to have three children, Owen, Joan and Marie. The family lived a modest life in Richmond. Frank worked as a wharf worker for the Victoria Stevedoring Company at the Victoria Dock where he aliased under the name of Frank or Stan Flinn. Flynn was Frank’s mother’s maiden name.

‘Flinn’ was well liked by his peers at the stevedoring company. His neighbour and workmate George Bromell claimed that Frank was ‘one of the best liked men in the place’.[26] He said that the man he knew always appeared to be normal and that he was very honest and a non-drinker.

Flinn seemed to be concerned about finances and according to George he spent a lot of his spare time working out racing systems, none of which seemed to pay off.

George claimed that Flinn had started complaining about his health and his sleep a few months prior to the tragic murder–suicide – again exhibiting many of the same symptoms that had afflicted him back in 1924. Not knowing about Frank’s past, George was unable to read the warning signs, and as Frank had ceased reporting to the Lunacy Department, his condition was unknown to any of the state’s authorities and they were therefore unable to take any preventative action.

George Bromell stated that over the previous four years Flinn and his two eldest children would visit him each Sunday. After the O’Brien’s failed to show up on Sunday 27 May 1934, George went to Flinn’s house on the Monday, and received no answer. He tried again the following day and there was still no answer, but he did notice a light burning in the front room and the key in the door. He came back again on 30 May. Still receiving no reply he left and returned later with his wife, getting his wife to make enquiries with the neighbours while he used the key in the door to let himself in.

What he found at that little house in Richmond would haunt him for the rest of his days.

Familicide in Australia

The act of family annihilation is rare. We have all heard stories on the daily news about mothers and fathers who take the lives of their children and sometimes themselves: this is commonly known as filicide. Familicide, where the lives of the spouse and one or more child is taken, and often involving suicide, is much rarer, but not unheard of.

A general inspection of the inquest records held by PROV (VPRS 24) reveal seven definite familicides, Frank’s included, occurring in Victoria between 1912 and 1971.[27] All seven cases were committed by the father, five were related to mental illness and altruism,[28] one to jealousy[29] and one was planned, allegedly in relation to a family life insurance policy, although the perpetrator disappeared on the day of the murders and has since been considered dead.[30]

More modern cases are harder to investigate as inquest files held at PROV are unavailable for the period post-1985.

Various reports similarly state that there are three main reasons surrounding familicide:

- mental illness; including post-natal depression and psychosis;

- misguided altruism (‘they are better off dead’); and,

- fear of abandonment, spite and revenge.[31]

Filicide is generally attributed to physical abuse, fear of the future and spousal punishment. However, unlike filicide, where there is often a history of abuse, familicide cases generally have an absence of previous violent behaviour, suggesting more altruistic motives as opposed to violence from the perpetrator.[32]

According to the cases above and the reports pursued, it is apparent that familicides are committed predominately by males[33] and are born out of the perpetrator’s altruistic need to do what they believe is best for the family that they love, respect and have abundant care for. Inherent mental illness combined with a fear of the future no doubt persuades such a person that the only way to escape these feelings of hopelessness and depression is to die and take those with you that would otherwise be left to suffer, effectively saving them from a world of pain and worry.

The system

How could it be that the system could have failed Frank and his family so drastically? A person known to have killed his first wife when in a confused state of mind is set free to start his life over, begins a whole new family and ends up destroying them all.

As stated, Frank was given three conditions for his release: that he would not live with his (current) children; that he would report to the Lunacy Department at Mont Park in relation to his mental condition every month; and that he would not resume his duties in education and teaching.

He certainly did not live with the children of the first wife he murdered. Frank’s brother Michael claimed that when Frank was released from Mont Park he moved directly to Melbourne, and did not even contact any of his existing children. He also did not resume his teaching duties, instead opting for a modest job as a wharf worker in Melbourne.

Michael claimed he did not recall sending the letter to the Chief Secretary requesting Frank’s release and promising that he and an another brother would provide O’Brien with assistance and care, even though the letters exist and are well-documented as having been received by the Chief Secretary. Michael claimed he only saw the deceased three or four times after he was released, the last time he saw him was in 1929. In August 1930, when the Inspector General of Mental Hygiene contacted Michael regarding Frank’s whereabouts, he responded that he had not seen his brother for almost a year. This was the last contact Michael had with his brother and he claimed he did not know Frank remarried, nor where he had been living with his new family or anything about his mental condition.

When quizzed about his responsibility for providing supervision to Frank, Michael stated that the department did not notify him that they had released Frank, and that they had not told him he was expected to fulfil that obligation. He said he did nothing to fulfil his promise as Frank went out of his way to avoid the family. Michael did not think too much about the situation as each time he saw Frank he seemed ‘perfectly sane’.[34]

It appears Frank’s family skirted their proposed responsibilities and accepted no blame for the events that transpired. What about those in charge of his release at Mont Park?

In the inquest into the O’Brien familicide, Dr John Catarinich pointed out that at various times throughout the proposal for release Dr Jones had advised the minister that the Lunacy Act 1903 did not allow for a criminal lunatic to be released on probation, and so the only option would be to release Frank completely. This shows that there was a fundamental flaw in the Lunacy Act at that time; surely, a person with a history of violence and killing, who suffered from a serious mental condition, should have been more closely monitored for the rest of his life.

As there was no provision for this kind of monitoring it was up to Frank himself to check in with Dr Jones. When O’Brien failed to turn up on a monthly basis it seems not much was done to locate him or determine his mental state.

Dr Catarinich stated that Frank was not discharged under the Lunacy Act 1903; he was discharged under the Crimes Act 1926 which states that the ‘Governor could impose such conditions as he thought fit for the patient’.

All this meant that there was effectively no way for the Lunacy Department to enforce the conditions of Frank’s release. Yet it seemed the Victorian Law Department were not aware of the conditions of the release, as it appeared no one at the Lunacy Department had stipulated any required involvement for the Law Department as part of Frank’s release. Surprisingly, at the time it seemed the departments did not seem to have very much do with each other when releasing potentially dangerous people into the community.

Dr Jones advised that Frank reported to him for a time, but then the periods in between his reports became longer, and then stopped altogether. Jones said that he had asked the police to get in touch with Frank to find out what had happened to him. Dr Jones advised that at the end of 1930 the police did find Frank and as a result of this he subsequently reported to Dr Jones, for the last time. Jones claimed that Frank was quite sensible and perfectly sane. He was also under the impression that he was in the care of his brother and that he did not know that Frank had remarried. Following the loss of contact with him in 1930, Jones did not pursue Frank personally or through the police.

The communication links between the Lunacy Department and the Law Department seem to have been rather fractured and inadequate in 1934, with no one wanting to take the blame or offer solutions for a situation such as this. In the inquest into the murders there are no concluding suggestions from the Lunacy Department or the Law Department about preventing future instances of this type of crime. Coroner Charles McLean concluded simply that the O’Brien family died from injuries sustained by Frank O’Brien, he being of unsound mind.[35]

In the end

The case of Frank O’Brien is truly devastating. But the conditions which led him to murder his family were not unheard of, especially during and around the Great Depression when employment, shelter, food and future prospects were scarce and dreary. The lack of comforts compounded with an uncertain livelihood may have compelled those with already fragile minds to desperate and irrational acts, which some perhaps altruistically imagined as providing final relief for their suffering families and a release from a bleak future.

During this time there was a lack of established mental health care and a lack of general understanding of mental illness, which certainly did not help the situation of people like Frank.

We can be thankful that our modern healthcare and better living conditions and social welfare provisions prevent these tragedies from happening as often as they once did.

Endnotes

[1] Margo Wilson, et al., ‘Familicide: The killing of spouse and children’, Aggressive Behavior, vol. 21, no. 4, 1995, p. 275, available at <http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1098-2337(1995)21:4%3C275::AID-AB2480210404%3E3.0.CO;2-S/pdf>, accessed 10 September 2014.

[2] Inquests of Francis O’Brien, Owen Francis O’Brien, Joan O’Brien, Marie Therese O’Brien and Rose Dorothy O’Brien, in PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, unit 1268, case 1934/825.

[3] PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, unit 2034, case 93 of 1924, King v. Frank O’Brien.

[4] ibid.

[5] ibid.

[6] Microfiche copy of teacher record books, PROV, VPRS 13718/P0 Teacher Record Books, Francis O’Brien Teacher number 12993.

[7] Marriage and birth information located on the births, deaths and marriages indexes available at Public Record Office Victoria.

[8] PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, unit 2034, case 93 of 1924, King v. Frank O’Brien.

[9] ibid.

[10] ibid.

[11] ibid.

[12] ibid.

[13] ibid.

[14] ibid.

[15] ibid.

[16] ibid.

[17] ibid.

[18] ibid.

[19] ibid.

[20] Inquests of Francis O’Brien, Owen Francis O’Brien, Joan O’Brien, Marie Therese O’Brien and Rose Dorothy O’Brien, in PROV, VPRS 24/P0, unit 1268, case 1934/825.

[21] ibid.

[22] ibid.

[23] ibid.

[24] ibid.

[25] PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, unit 2034, case 93 of 1924, King v. Frank O’Brien.

[26] Inquests of Francis O’Brien, Owen Francis O’Brien, Joan O’Brien, Marie Therese O’Brien and Rose Dorothy O’Brien in PROV, VPRS 24/P0, unit 1268, case 1934/825.

[27] Please note, PROV, VPRS 24 Inquest Deposition Files at the Public Record Office Victoria are closed for records relating to inquests post-1985, hence the lack of more modern examples.

[28] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, unit, 884, case 1912/865; unit 1097, case 1926/842; unit 1344, case 1938/25; and unit 1597, case 1948/1108.

[29] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, unit 866, case 1911/492.

[30] PROV, VPRS 24/P2, unit 373, case 1971/586, inquests relating to the Crawford family murders.

[31] M Liem and F Koenraadt, ‘Familicide: a comparison with spousal and child homicide by mentally disordered perpetrators’, Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, vol. 18, no. 5, December 2008, p. 313, available at <http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cbm.710/pdf>, accessed 8 October 2014.

[32] ibid.

[33] Wilson, ‘Familicide’, p. 275.

[34] Inquests of Francis O’Brien, Owen Francis O’Brien, Joan O’Brien, Marie Therese O’Brien and Rose Dorothy O’Brien, in PROV, VPRS 24/P0, unit 1268, case 1934/825.

[35] ibid.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples