Last updated:

‘“Where Fire Risks are Great”: A Tale of Arson, Bureaucracy and the Schoolyard’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 9, 2010. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Kirsten Wright and Antonina Lewis.

This is a peer reviewed article.

The discovery of damaged and burnt volumes in the Victoria University Archives led the authors on an investigation into the circumstances of a fire which occurred at the Footscray Technical School in 1953. Contemporary attitudes to fire protection in public schools, and life in Footscray, as revealed through records of the time, are also discussed with reference to the school.

The Changing Face of Footscray

Peaceful picket-fence environs of 1950s Australia have been well mythologised in our national culture, but this gladioli-tinted picture does not account for the totality of suburbia. Contemporary newspaper reports and archival documents, as well as the published histories these records support, substantiate a claim that in Melbourne’s inner-west cottage, roses and emerald lawns were sharing real estate with any number of less salubrious inhabitants: abattoirs, chemical plants, sly-grog stills and slumlords. The industrial profile of the area was not new – Footscray’s beginnings were in quarries, riverside slaughterhouses, and melting factories for the reduction of livestock to tallow – but where factory owners and local businessmen had once chosen to establish homes near to their capital interests, close physical proximity was becoming increasingly unnecessary for the conduct of business operations, just as the culminating effects of a century of industrial pollution were rendering it more undesirable. Abetted by post-war immigration and early indicators of a shift away from heavy industry, the changing demographics of the area contributed to a community that was both optimistic and, at times, incendiary. Traditional battles between territorial ‘larrikin’ gangs of neighbouring suburbs were now augmented by battles with and between ‘New Australian’ youths. At the same time, a strong sense of civic pride is evidenced by the numerous municipal and community efforts that assisted with improvements to local schools and amenities, and to the establishment in 1947 of an Avenue of Honour in Geelong Road.

A survey of Footscray district newspapers of the period unfolds a catalogue of civic celebrations juxtaposed with stories of quarrels and altercations (on a scale ranging from comedic to criminal), surprisingly frequent arson attempts, and sporting pages regaling amateur boxing bouts alongside the rough and tumble exploits of Footscray Football Club, whose sole premiership in 1954 gave rise to much jubilation. Equipped with an underdog sensibility and a strong sense of civic pride, 1950s Footscray constituted itself through the public record as a habitat for battlers, with the reportage of both public and domestic, sanctioned and unsanctioned violence indicating an atmosphere where ‘mud and blood’ had not yet lapsed as paradigm colours for the region.

Mud and Blood

Brown and red (‘mud and blood’) were, first, colours of the E company 7th battalion – roughly half of whom enlisted against a Footscray address,[1] and who counted among the Australians to see service in Gallipoli. Brown and red were subsequently chosen, in tribute, as school colours for the fledgling Footscray Technical School (FTS) when it opened its doors in 1916, only months after the conclusion of the Gallipoli campaign.[2] The first school magazine, published in 1919 – also named the Brown and Red – includes an FTS Honour Roll, listing the names of soldiers drawn from the ranks of staff and students. However, aspirations for Footscray’s youth to identify as more than cannon fodder or as cogs in an industrial machine was a fundamental underpinning to the educational philosophy of Charles Archibald Hoadley, first principal of FTS. With experience in teaching (he was employed as a lecturer at the Ballarat School of Mines at the time of his appointment to head FTS), but unproven as an administrator, Hoadley was considered by some to be a strange selection for the role – and indeed had not been first choice for the position.[3]

A mining engineer, geologist, alumni of Mawson’s 1911 Antarctic expedition, and only 29 years of age when the new Footscray Technical School opened, Hoadley held comparatively limited experience in the educational arena. And yet, as it turned out, what the school had engaged was ‘not an administrator but an educationalist, and . . . the chance to create an important local institution rather than the narrow, limiting type that seemed almost inevitable at that time’.[4] Hoadley’s vision for FTS and its students was in stark contrast to the views of those such as Donald Clark, Chief Inspector of Technical Schools, who in 1931 stated to the Board of Inquiry Regarding the Administration of the Education Department his position that ‘Since many boys would work in tin sheds . . . [they could] learn to work in them too.’[5]

Like many endeavours in Footscray, the establishment of a technical school had been something of a battle. However, by the end of 1915, Footscray had at last managed to secure the land, finance, industry backing and government support required to open a new technical school in the area – more than five years after the idea was first proposed by James Jamieson in an editorial to his Footscray advertiser.[6] Despite having Council support,[7] the proposal had not proved straightforward to achieve. In order to move beyond the realm of rhetoric, a new technical school required the purchase or donation of land, procurement of funds to build and equip the establishment, and the support of local businesses in offering day release for their apprentices to attend classes. All this needed to occur in an environment where the Victorian State Government was reserved in its financial support for education, in preceding years having spent only one-third the amount per capita as that of the neighbouring state of New South Wales.[8] An early pledge from the state for £5,000 towards the cost of establishing the school was contingent on a suitable site being made available for this purpose, but the offer lapsed in 1912 after consensus on an appropriate location proved unattainable. The Advertiser later claimed: ‘Footscray’s attempt to secure a technical college for the youth of the district would provide humorous reading were it not [for] the bungling which took place in the early stages of negotiations. . . ’.[9]

comprehensive aim of promoting the development of responsible citizens, not merely as economic units destined to fall into a prepared place in the present industrial structure, but as the creative and self reliant men of the future who will be competent to play a decisive part in directing, shaping and improving the industrial system.[11]

By the late 1930s, Footscray Technical School had weathered a series of funding cutbacks and the threat of closure of its Senior Section. The possibility that FTS might relinquish its senior classes to the Working Men’s College (later RMIT) was canvassed during the 1930s as part of the government’s Inquiry Regarding . . . the Education Department (McPherson Report).[12] However, having survived this threat, the school was thriving under Hoadley’s stewardship to the extent that demand for places had far outgrown the numbers that could be accommodated at the original Nicholson Street site. Extensions to the buildings were carried out in 1938 but were not sufficient to ease the pressure, and in 1941 close to 300 applicants hoping to attend FTS had to be turned away.[13] In September of the same year, the foundation stone was laid on Ballarat Road for new buildings – on a site Hoadley had first proposed be used to extend the school twenty years earlier.[14] By 1943, the new buildings were ready for occupancy, with expansion of both the Nicholson Street and Ballarat Road sites continuing throughout the 1940s, boosted significantly by the provision in 1947 of £120,000 in Commonwealth funds for additional buildings and equipment at Ballarat Road, including the construction of a new administrative block opposite the Geelong Road intersection.[15]

The grant was a bittersweet success, however, in light of the loss of Charles Hoadley, who died on 26 February 1947. Later that year Joseph Aberdeen was appointed as the new principal, but his untimely death in 1951 left the post vacant once again. Next to take on administration of the expanding institution was Howard Beanland, who provided another period of stable leadership (lasting until his retirement in 1967) and who engineered the rationalisation of FTS’s increasingly sprawling operations, as well as overseeing the transition from Technical School to Technical College. Building on Hoadley’s vision, Beanland consolidated the school’s position at the apex of technical education in Melbourne’s western region and brought it to the brink of a new era – the emergence of a new institution in July 1968, the Footscray Institute of Technology, predecessor to Victoria University (VU).

A Mystery Uncovered

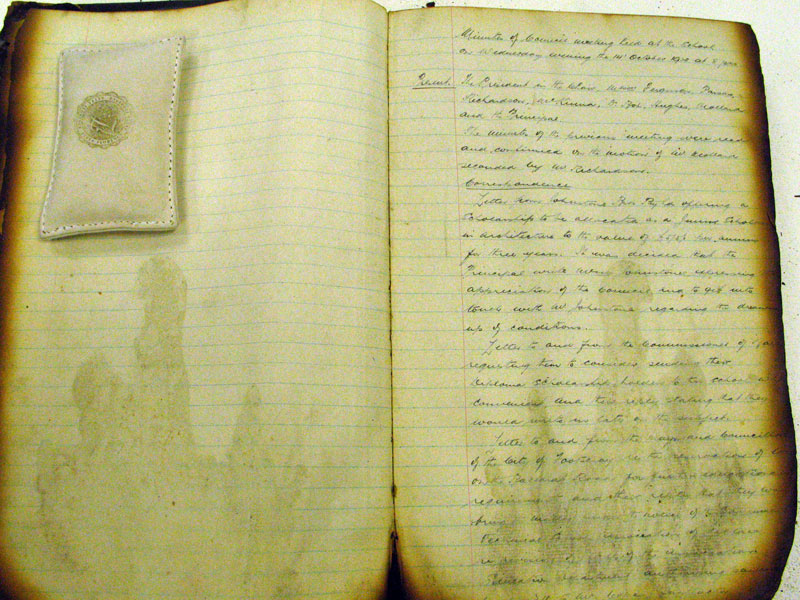

The rapid social change wrought by the effects of post-war immigration, mobilisation of women into the workforce and the first wave of globalisation created an environment that, while not unique to Footscray, was heightened by the industrial and working-class histories of the suburb. It was, in part, this rich vein of social history that encouraged Antonina Lewis to apply for the position of Archivist at VU, but on taking up the position in 2007 she found surprisingly few pre-1955 records surviving in the university’s archives. Among those extant were several fire-damaged volumes, comprising four of the first five books of FTS Council minutes, however the collection documentation offered no insight into the cause of injury. The official history of the institution, Carolyn Rasumssen’s Poor man’s university, offered only a single footnote as a clue, noting that a fire had occurred in 1953 in which ‘Many school records were destroyed’.[16]

Victoria University Archives, VUS 731.

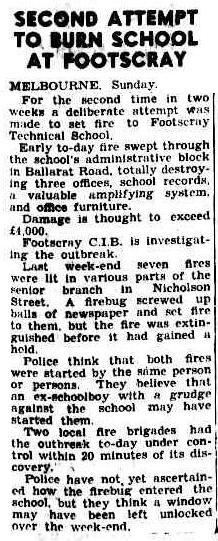

As the sole Archives staff member, with the customary backlog of archival processing to contend with, Antonina contented herself with repackaging the volumes and shelving the mystery. However, when Kirsten Wright joined the Records Services department of VU in early 2009, the case was revisited after she discovered a newspaper article from the Canberra times through the Australian Newspapers Online database.[17] Intrigued by this glimpse into the previously unknown disaster which befell the school, and with little information present in the University Archives, Antonina and Kirsten set out to discover the circumstances of the fire, to better understand what had become of the records in 1953. In piecing together the puzzle of the fire, they discovered that the overall topic of fire protection in schools – let alone the specific fire which had left the VU Archives with few records pre-1953 – was not without controversy.

Fire Protection in Schools

For public (including technical) schools in the 1950s, it was the responsibility of the Department of Education to ensure adequate fire protection was provided. As with all building and related items for public schools, the Department of Education provided direction and authorised specific work, which was then carried out by the Public Works Department (PWD). While the Department of Education was obligated to ensure that public schools had escape routes for students and staff, the protection of property was seen as an unnecessary expense. In 1949, a file note neatly summarised the department’s position on the topic:

The Assistant Chief Architect … is of the opinion that these installations [automatic fire protection systems] do not appear to be necessary … I am doubtful whether the risk of a fire starting in a school building while it is unoccupied is sufficient to warrant [the] expenditure …[18]

In practical terms, this meant that the department was willing to fund the provision of fire escape stairs and other physical escape routes for use by staff and students, but not the installation of fire hoses, alarms and automatic sprinkler systems. It was acknowledged that perhaps technical schools – such as FTS – may require additional fire protection, ‘where fire risks are great’; however, this did not translate into significant improvements for technical schools.

The issue of lack of fire protection in schools – both metropolitan and rural – did not go unnoticed by concerned groups. On 30 June 1952, the Victorian Federation of Mothers’ Clubs submitted a copy of the resolution passed at their annual conference for consideration by the Minister of Education, stating that, at a minimum, country schools should be equipped with proper fire-fighting equipment.[19] It was not just groups intimately associated with schools who thought that the fire protection facilities were inadequate. On 27 September 1952, the chief officer of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade (MBF), in an article appearing in the Age, stated that most fire-fighting equipment in schools was ‘deplorable’ and that schools – and the Department of Education – had been lulled into a false sense of security as there had been no deaths in school fires in the previous ten years.[20]

Despite the amount of publicity circulating about the lack of adequate fire protection, the Department of Education did not alter its policy. It was too expensive to install new fire equipment at each public school, they said – even if the Public Works Department did the installation and the schools paid for the maintenance and upkeep of the equipment. By 1954, the policy had relaxed slightly in that basic fire protection equipment (such as extinguishers and hoses) was available to any school that requested it, but it was still not compulsory – nor, when such equipment was installed, were staff trained in its use.[21] More expensive fire protection equipment, such as fire alarms and sprinklers, was still deemed an unnecessary expense – to the point where the Department of Education advised its staff that ‘there is no need to forward to the Public Works Department requests for the installation of thermostatic fire detectors in school buildings’.[22] By 1959, requests had been sent to the Department of Education from a variety of groups urging a change to the policy on fire protection that would mandate compulsory fire protection equipment in all public schools, however the department continued to maintain the policy of only providing basic fire-fighting equipment and ensuring that buildings had adequate escape routes for people to use.

Like many public and technical schools at this time, FTS had no fire-fighting equipment. In 1952, the School Council became concerned about the lack of fire protection at both the Ballarat Road and Nicholson Street campuses, and requested that the MFB inspect both campuses and submit a report and recommendations regarding fire protection. On 12 September 1952, Principal Beanland wrote to the Department of Education reporting the MFB recommendations.[23] For Nicholson Street, the MFB had recommended that automatic sprinklers be installed, that an additional escape stair be constructed on one building, and that a fire resisting store be provided. For Ballarat Road, it was recommended that an automatic fire detection system be installed so that the fire brigade was alerted immediately in the event of a fire, that fire hydrants be installed (for use by the fire brigade only), and, as for Nicholson Street, that a fire resisting store be provided.

The recommendations were forwarded to the PWD in late 1952/early 1953 for the PWD to assess how much the request would cost and whether the recommendations were feasible. By February 1953, permission had been granted for an escape stair to be installed at the Nicholson Street campus[24] – but there was no indication that construction began in 1953. There were also signs that the Department of Education was willing to fund the construction of further fire protection equipment both at Nicholson Street and Ballarat Road. A handwritten file note dated March 1953 authorised the requisition of £5,950 for the installation of an automatic sprinkler system at Nicholson Street. Further works were described (but not authorised), and the department noted that ‘the installation of automatic sprinklers is recommended as a protection of property, rather than as a safeguard to the lives of students and staff’.[25] The departmental concern about safeguarding students and staff also explains the (relative) speed with which the authorisation to build the escape stairs at Nicholson Street was given, compared to the lack of urgency with other fire protection measures.

By June 1953, no fire protection systems had been installed at FTS – on either campus. There were adequate escape routes for students and staff if a fire occurred during school hours, but nothing to protect the buildings outside of these times.

Fire Breaks Out

In the early hours of Sunday, 21 June 1953, the alarm was raised about a fire at the Nicholson Street campus. At approximately 1.30 am, an unknown passer-by alerted the Footscray police to a fire burning within the school area.[26] When the police and fire brigade gained entry to the school (according to one newspaper report, they were initially ‘foiled by the iron grilles at the doors’),[27] they found seven small fires burning in the office area. The fire brigade quickly controlled the fires, and little damage was done except some minor damage to a switchboard. Investigating police found seven piles of torn-up paper and books, used to start the fires. The Advertiser speculated that the intruders had been frightened by the quick arrival of the police and fire brigade, who had thwarted their intention to do more damage.[28]

The arson attempt at the Nicholson Street campus was reported widely. The Argus, the Age and the Sun all ran stories on either page 1 or page 3 of their next editions, published on Monday 22 June. The local Footscray papers, the Advertiser and the Mail, provided some additional details about the fires. The School Council, already aware of the risk that fire posed to the school given the lack of fire protection, acknowledged their luck in serious damage being prevented. At their meeting on June 23 it was resolved that ‘an expression of thanks, to the person unknown . . . be recorded per medium of the local press’,[29] and a thank-you note was duly printed in the Advertiser.[30]

Unfortunately for FTS, its fire troubles were not over. The following weekend, on Sunday June 28 at about 3 am, a passing motorist alerted the fire brigade to another fire at the school.[31] This time the blaze was at the Ballarat Road campus, home to the Junior School. Units from the Footscray and Yarraville fire stations attended, and the fire was brought under control within twenty minutes, although it was another hour before the fire was completely extinguished.[32] Once again the actions of a concerned member of the community had minimised the impact of the blaze, but this time the damage suffered was severe.

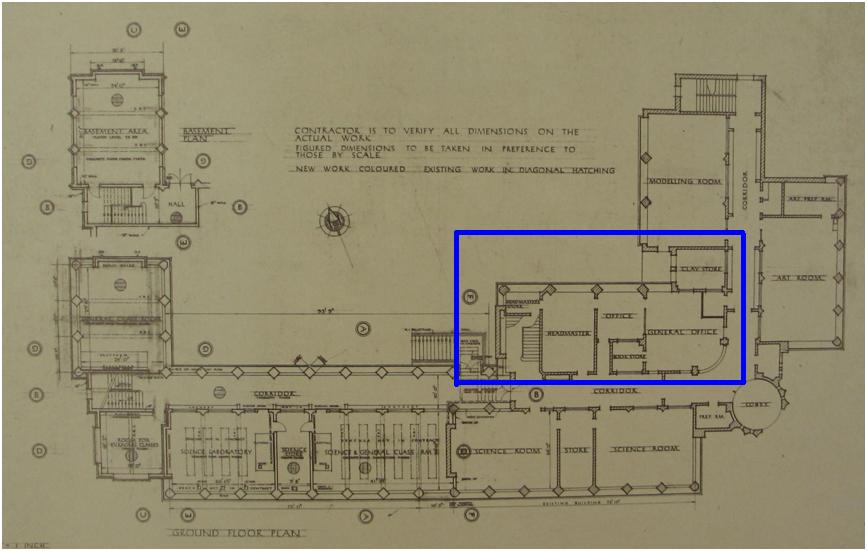

When police entered the campus once the fire was out, they established that the fire had started in the administrative area, gutting the headmaster’s office, book room, and general office. Property damage was extensive, and the school’s records did not escape the flames, with the Footscray mail reporting that the ‘main loss was the destruction of irreplaceable students’ records, dating back to when the junior school was first set up . . . in 1916’.[33] In addition to infrastructure damage and the loss of key records, text books and stationery supplies were also destroyed, and smoke damage meant that many walls and ceilings in the building needed to be repainted. The Argus noted that the heat from the fire was so severe that ‘scores of windows in the office block were burst by the heat’.[34] While the police could not establish the cause of the fire, the damage was bad enough that the Minister for Education – and former FTS Council member[35] – Ern Shepherd, toured the site on Sunday June 28, and the school was closed to students on June 29.[36]

PROV, VA 669 Public Works Department, VPRS 10516/P3 Photographs and Negatives of Government Buildings, Unit 10.

After visiting the fire-damaged site, Shepherd remarked that ‘we were lucky to get out of it so lightly’,[37] despite the damage bill being estimated in the thousands of pounds. This presents a contrast to the general attitude of the Department of Education, mentioned above, which continuously stated that fire protection equipment primarily for the protection of school property was not needed, and that the cost was too great.

The fire at Ballarat Road was reported widely in both the Melbourne-wide and local Footscray newspapers. On June 29, the Monday after the fire, the Argus, the Age and the Sun all ran stories on page 2 or 3. The fire also made the national papers, with the Canberra times running the story on its front page, as already noted.[38] All initial reports in the newspapers focused on a possible connection between the Nicholson Street and Ballarat Road fires, with some speculating that perhaps a disgruntled ex-student was behind the attacks.

The Aftermath

Internally at FTS there were few formal mentions of the fire compared with the widespread and prominent external coverage. While the fire was noted in the FTS Council minutes many times, it was only in the context of procedural reporting about correspondence received and sent, and building works being undertaken as a result of the fire. The Principal’s Report in the next published edition of the annual Blue and Gold magazine made no mention of the fire; the only reference to the event is a joking remark made by some students in the form reports:

Speaking of fires – and even if you weren’t you undoubtedly will some time or another – we want to say here and now, for the record, that the ones we had earlier in the year were not ours at all, it was probably four other people …[39]

It is interesting to consider the difference between the wide-scale reporting provided by the newspapers and the lack of internal discussion of the fire within the school. All reports and correspondence to the Department of Education highlight that this was a disruptive event, and that repairs were not completed for some time. While damage was not so extensive that the school could not operate, some of its activities were now made more difficult, particularly those to do with administration.

As soon as the fire occurred, Principal Beanland communicated to the Department of Education:

We wish to report that a fire occurred in the offices of our Ballarat Road Unit at approximately 3 am on Sunday, 28th inst. The furniture and contents of the General Office, Headmaster’s Office, and Book Room have been completely destroyed. The matter has been reported to the state Accident Insurance Co.[40]

The department was quick to begin organising the repairs to the Ballarat Road campus. A request for the PWD to undertake repair work was given on 3 July 1953 and marked as ‘urgent’.[41] Following estimates on the amount of work required, approval was provided for £4,553 worth of work to be undertaken. At the request of Beanland, this work was to include the provision of a strong room and fire-fighting equipment. Additionally, as Beanland’s note to the Department of Education indicates, an insurance claim had been submitted immediately. The State Accident Insurance Office responded, and a cheque was received by 22 September 1953.[42] Unfortunately for FTS, the ‘full settlement of claim’ only came to £2,500.

While quotes and approval for the repair work were obtained relatively quickly, the actual repairs were slow to begin. By the end of September 1953, calls for tenders to undertake the work had not yet occurred. FTS Council was concerned at the lack of action, and Beanland again wrote to the Department of Education, requesting (somewhat optimistically) that the work be completed before the start of the coming school year:

The School Council is perturbed that up to the present tenders have not been called for repairs to fire damage at our Ballarat Road Unit of the School.

I am directed to request that the matter be expedited and that a clause be inserted in the contract – ‘That the work should be completed by the 31st January, 1954’ …[43]

Work did not begin on the repairs until 5 February 1954, with specific works undertaken as a result of the fire finally completed on 22 July 1955, more than two years after the blaze occurred. The final cost of the repairs came to £5,506,[44] an amount more than the original quote, and substantially over the insurance settlement received.

It is impossible to know how much the damage from the fire may have been limited if automatic fire detection equipment had been installed at Ballarat Road prior to the fire; however, it is likely that the damage would have been much less. In the absence of any such protection, school activities were significantly disrupted and the loss of irreplaceable records dating back to FTS’s establishment in 1916 incurred a lasting impact on the social and corporate memory of the institution and its successors, including VU.

Conclusion

The reason behind the missing records and charred volumes in the VU Archives has now been explained. Our investigation into the 1953 fire at Ballarat Road revealed many things. We uncovered specific information about the event itself, the inner workings of FTS, the concerns of the School Council, and the protocols and politics that surrounded all schools’ dealings with the government of the time. Other primary sources offered a glimpse into life in 1950s Footscray, revealing that although arson attempts were not uncommon in the area – with local newspapers seeing fit to report when the frequency of fires reduced enough to be noteworthy – this behaviour was balanced against a strong sense of community, as evidenced by those who alerted authorities to the two fires at the school. The records document frustration at the damage done by the fires, but also optimism and the firm resolve to repair and improve: to shape from the ashes something better than what stood before.

Endnotes

[1] Australian War Memorial Roll number: 23/24/1, available online at <http://www.aif.adfa.edu.au:8080/showUnit?unitCode=INF7CE>, accessed 6 April 2010.

[2] FW Meymott, editorial in Brown and Red magazine, 1919, Victoria University Archives,

VUS 400.

[3] Footscray advertiser, 18 December 1915.

[4] C Rasmussen, Poor man’s university: 75 years of technical education in Footscray, Footprint, the press of the Footscray Institute of Technology, 1989, p. 38. This official history was commissioned by the institute.

[5] Evidence given by Donald Clark to the Board of Inquiry Regarding the Administration of the Education Department, 10 July 1931, p. 971. PROV, VA 714 Education Department, VPRS 2567.

[6] Footscray advertiser, 19 June 1909.

[7] Footscray City Council meeting May 1910, cited in J Lack, A history of Footscray, Hargreen Publishing in conjunction with the City of Footscray, 1991, pp. 201-2.

[8] Rasmussen, Poor man’s university, p. 18.

[9] Footscray advertiser, 26 December 1914.

[10] Footscray Technical School Prospectus, 1920-1921, Victoria University Archives, VUS 21.

[11] Footscray Technical School Prospectus 1947-1948, Victoria University Archives, VUS 21.

[12] Rasmussen, pp. 92-3.

[13] Footscray advertiser, 8 February 1941.

[14] Letter from C Hoadley to Department of Education, 14 June 1923, Victoria University Archives, VUA 2004/04.

[15] Rasmussen, p. 97.

[16] ibid., p. 138.

[17] Canberra times, 29 June 1953, p. 1, ‘Second attempt to burn school at Footscray’, available at <http://newspapers.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/page/701267>, accessed 22 October 2010.

[18] PROV, VA 714, VPRS 8819/P1 School Building General Correspondence Files, Single Number System, Unit 16, File note 18 October 1949.

[19] Letter from the Victorian Federation of Mothers’ Clubs to the Minister of Education, received 30 June 1952, in ibid.

[20] Age, 27 September 1952, p. 4.

[21] Report by WG Finigan, Inspector of Works, 10 June 1954, PROV, VPRS 8819/P1, Unit 16.

[22] Memo, 4 May 1953, in ibid.

[23] Letter from H Beanland to Department of Education, 12 September 1952, PROV, VA 714, VPRS 9513/P1 Technical Schools Building Files, Unit 31.

[24] Requisition of works, in ibid.

[25] File note, 26 March 1953, in ibid.

[26] Age, 22 June 1953, p. 3.

[27] Footscray advertiser, 26 June 1953, p. 16.

[28] ibid.

[29] Footscray Technical School Council, Minutes of Council meeting 23 June 1953, Victoria University Archives, VUS 731.

[30] Footscray advertiser, 3 July 1953, p. 6.

[31] Age, 29 June 1953, p. 3.

[32] Footscray mail, 4 July 1953, p. 4.

[33] ibid.

[34] Argus, 29 June 1953, p. 2.

[35] Rasmussen, Poor man’s university, p. 132.

[36] Footscray mail, 4 July 1953, p. 4.

[37] Age, 29 June 1953, p. 3.

[38] See note 17 above.

[39] Form 8C report, in Blue and Gold, 1953, p. 23, Victoria University Archives, VUS 42.

[40] Letter from H Beanland to Department of Education, 29 June 1953, PROV, VPRS 9513/P1, Unit 31.

[41] Requisition notice, Public Works Department, 7 July 1953, in ibid.

[42] Footscray Technical School Council, Minutes of Council meeting 22 September 1953, Victoria University Archives, VUS 731.

[43] Letter from H Beanland to Department of Education, 30 September 1953, PROV, VPRS 9513/P1, Unit 31; see also Footscray Technical School Council, Minutes of Council meeting 22 September 1953, Victoria University Archives, VUS 731.

[44] PROV, VPRS 9513/P1, Unit 31, File note 22 July 1955.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples