Last updated:

'Keeping Order: Motor-Car Regulation and the Defeat of Victoria's 1905 Motor-Car Bill', Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 3, 2004.

ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Rick Clapton.

At the turn of the twentieth century some upper-class Victorians became motorists; consequently, for the first time ever, regulation and policing intersected with this class of society. By 1905 so many concerns had been raised about compromised public order and safety that the Victorian State Government attempted to implement a Motor Car Bill based on its English predecessor (1903). Wealthy motorists possessed power and influence, however, which contributed to the postponement of legislation until 1910. Additionally, parliamentarians were drawn from the same social class as motorists, and, in creating regulation, they were potentially regulating their peers, colleagues and friends. The private motor-car also brought with it new issues of civil liberty and responsibility. Finding a balance between the two continued to be a problem, as private transport gradually became affordable for middle- and working-class people, and both the number of regulations and the power of the motoring lobby increased.

Introduction

On Friday, 31 August 1901, Jack Proctor, the General Manager of Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. (Australasia), drove the company’s promotional car along Flemington Road , accompanied by Harry James, Dunlop’s Advertising Manager.[1] Their destination was the Flemington Showgrounds where the new machine, no doubt, would be a great attraction for Melburnians. Near the racecourse, horses were crossing Epsom Road; in response, Proctor slowed the car to an estimated eight miles per hour (mph), but did not stop. Windsor, a restive and skittish colt, bolted and Proctor desperately, almost aggressively, executed evasive manoeuvres; but the two-and-one-half-horsepower De Dion motor-car was slow to respond. Windsor charged the car, crashed into the vehicle’s step and sustained a broken leg. As a result the animal was destroyed.

Samuel Bloomfield, Windsor’s owner, sued Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. for damages to the amount of £499 – a large sum of money at the beginning of the twentieth century.[2] In April 1902, Chief Justice John Madden of Victoria’s Supreme Court admitted ignorance – like most Victorians – regarding motor-cars, and requested that the managers give a demonstration on William Street outside the court building. Both ardent motorists, Proctor and James believed that the superior braking, steering and acceleration qualities of the automobile would illustrate that Proctor had done everything expected of a ‘reasonable gentleman’, and consequently that Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. would succeed in this ‘media-charged’ civil liability suit. Judge Madden observed the braking distance, the speed and handling capabilities of the new machine; as a result of Proctor’s showcased driving performance he ruled in favour of the plaintiff. Bloomfield was awarded £250 in damages. Madden ruled that ‘it was plain that the car had travelled at a very rapid speed. The persons driving the car knew they could stop it at any moment, and that it had frightened horses before; yet they did not stop when they saw that the colt was alarmed’.[3] The motor-car should have proceeded only after the horses had cleared the thoroughfare.

As this example shows, upper-class and wealthy Victorians who became motorists at the turn of the twentieth century exposed themselves, for the first time ever, to regulation and the police. But unlike Proctor and James, many were able to use their political influence with the authorities; their ability to defend themselves in court also helped to stave off conviction. At this period, most motorists were drawn from the same social class as the parliamentarians who were mandated to create new motor-vehicle legislation. In this article I will explore the intersection between ‘automobilism’[4] and motoring laws and regulations in Victoria between 1900 and 1905, with emphasis on the unsuccessful Motor-Car Bill of 1905. In particular, I shall examine the conflict that resulted between motorists, authorities and other road-users as Melbourne, like other motoring cities, moved towards a highly regulated traffic system.

English Road Laws

Road laws at the beginning of the twentieth century were obfuscated by the myriad of statutes which could be applied to public road spaces and the vehicles that drove on them. In addition to the Locomotives on Highways statutes 1861, 1865 and 1878, Imperial authorities could also rely on the Highways Act 1835, the Hackney and Carriages Act 1843, Vagrancy Laws of 1744, and several others.[5] England first brought regulation to bear on motorised transport in 1861, under the Imperial Locomotives on Highways Act 1861 – amended 1865 and designed to deal with steam-driven agricultural and industrial traction engines travelling on highways – in which the notorious ‘Red Flag’ clause stipulated that a person with a red flag must proceed the vehicle at a distance of sixty yards. The original legislation limited steam engines to 12 tons and speeds of 10 mph; the amendments further restricted speeds to 4 mph on rural roads and 2 mph in towns and cities. Further, the steam locomotive was to be operated by a minimum of three people: one to drive the machine, another carrying a red flag to warn horse traffic, a third to assist drivers of horse-drawn vehicles; and a fourth if there were waggons.[6] The law was again amended in 1878 and granted local councils the option of using the ‘Red Flag’ as well as reducing its leading distance to a more manageable twenty yards, but few councils chose to abolish it.[7]

In 1896 the Imperial statute was further amended to recognise that locomotives were starting to be used for personal transportation. The Locomotives on Highways Act divided vehicles into two categories: light locomotive or carriages, and those exceeding three tons. Light locomotives were restricted to a speed limit of 14 mph, were to carry a bell, and not emit any visible smoke. Local councils could create by-laws restricting vehicles on bridges to prevent damage, and the Local Government Board ‘may prohibit or restrict the use of locomotives’ if it deemed them a danger to the public along crowded streets.[8]

The 1896 Act did not repeal other statutes that could also be used to control road space; most statutes that controlled street behaviour effectively controlled working-class street behaviour. On 18 April 1903, for example, the Imperial Hackney and Carriage Act 1843 was utilised in the case of Henry George Allendale when he appeared before Magistrate Mr Curtis Bennett in Marylebone for ‘furiously’ driving an omnibus. Authorities had previously warned drivers of London Road Car Co., and the rival company London General Omnibus Co., about racing between the suburbs of Kilburn and Fulham. Police set up a special task force after public complaints were received regarding the racing and ‘furious’ driving. The police constable who testified at the trial stated that Allendale, when overtaking the other bus, was driving ‘at least ten mph’.[9] Because this was Allendale’s second offence he was sentenced to one-month’s hard labour.[10] On 27 April 1903, General Laurie, during parliamentary debates, questioned the Under Secretary to the Home Office, asking if he was aware of Allendale’s sentence, and wanted to know if similar proceedings were being taken against motor-cars. Although he repeated the question, the Home Secretary offered no answer.[11] As a bus driver, Allendale was part of the proletariat, unlike most motorists drawn from the upper-classes; he was probably unable to legally defend himself in court, so his deviance was made a public example – thus the severity of his sentence. In 1903, average urban road speeds were approximately 6 to 8 mph; therefore, by exceeding the relative speed limit by a significant margin, Allendale was found to be endangering not only other road-users, but also the passengers on his omnibus.[12]

The Imperial legislation of 1896 became the fundamental statute that formed the basis for subsequent motor-car legislation; however, enforcing speed limits remained problematic. While ostensibly introduced for safety reasons, speed was complicated to measure, often requiring two constables; expensive timepieces were legally required, and professional engineers had to be employed to measure the 220 (1/8 mile) or 440 (1/4 mile) yards.[13] Moreover, policing speed limits exacerbated class conflict between wealthy motorists and working-class constables; as a result, these were difficult, if not impossible, to enforce and prosecute during the early years of motoring because the motorists were able to exploit their privilege and access to legal resources. As a result, the 1896 legislation was again revised: Section 4, sub-section 1 now read

that a driver of a light locomotive when used on a highway, shall not drive at any speed greater than is reasonable and proper having regard to the traffic on the highway, or so as to endanger the life or limb of any person, or to the common danger of passengers.[14]

In the 1903 British Motor Car Act, this clause, in response to Supreme Court appeals,[15] was expanded further:

If any person drives a motor car on a public highway recklessly or negligently, or at any speed or in a manner which is dangerous to the public, having regard to all the circumstances of the case, including the nature, condition and use of the highway, and to the amount of traffic which actually is at the time, or which might reasonably be expected to be, on the highway, that person shall be guilty of an offence under this Act.[16]

Public pressure in England surrounding the automobile’s speed and compromised road safety forced parliamentarians to introduce and implement the 1903 Motor Car Bill. Introduced into the House of Lords by Lord Balfour of Burleigh, the Secretary of State for Scotland, on 7 July 1903, Parliament sat long hours to push the Bill through before the summer break.[17] The new motor-car legislation, in addition to Section 1, which allowed justices to prosecute many different types of traffic infringements such as negligent or reckless driving, or driving at a speed considered dangerous to the public, implemented additional stipulations: motorists were to be licensed and a minimum of seventeen years old; car registration was made mandatory; a car now required a prominent number plate; speeds limits were fixed at 20 mph in the country and 10 in the city; and the maximum penalty was set at £10 for a first offence, £20 for a second and £50 for the third, and even possible gaol terms. It also became an offence not to produce a licence when requested by a constable. Finally, in response to concerns raised during the parliamentary debates, it was agreed that the new legislation would be effective for three years, after which a Royal Commission would be conducted.[18]

British parliamentarians had attempted to shore up concerns about public safety by maintaining the discretionary element common to earlier road and traffic legislation. This discretionary clause allowed constables to throw a wide net over the dangers of increased road speeds. Many motorists defended themselves in court, but were convicted, which reveals the legislation’s validity, though there were of course stories of constables being bribed or ‘browbeaten’, motorists giving false information, and ‘gentlemen’ in court accusing constables of insolence and impertinence.[19] Overall, however, though aspects of the legislation remained problematic (as revealed in the 1906 Royal Commission of Motor Cars), England experienced considerable success in prosecuting delinquent motorists under this Act.[20] Australia inherited England’s legal institutions;[21] and so, notwithstanding an initial setback in 1905, Victoria adopted the legislation, almost verbatim, in 1909.

Early Motoring in Victoria

Although by the turn of the twentieth century Victoria had formulated its own laws to regulate roadways and the vehicles that used them, England had offered a precedent. Importantly, Victoria’s Traction Engine Act of 1900 did not apply to motor-cars.[22] The State Government was unable to enact specific motor-car legislation until 1909, in part because motorists were drawn from the same social class as politicians, though attempts were made in 1905, as we shall see. During the first decade of the new century, Victorian police and authorities relied almost exclusively on the 1890 and 1891 Police Offences Act to control street spaces; discretionary charges were brought to bear on a variety of offences and vehicles – horse-drawn, bicycles and self-propelled. In finding for Bloomfield’s compensation, Judge Madden followed the 1890 Act, which stated that one must not ride or drive ‘furiously’ or ‘negligently’ on any public street.[23]

The Victorian Police Offences Act 1890 was widely used to control road traffic before the State’s 1909 Motor Car Act; however, it was primarily geared toward roadways as a public space. Most of the Act’s legal stipulations were directed at a citizen’s activities on the street and preservation of the road surface, while few regulations governed the movement of traffic. For example:

no person shall dispose of garbage, night soil, or carry excrement in the roadway; or drag anything which would cause damage to the street; one shall not burn anything or leave flammable materials in the road; and passageways and walkways should be clear of offensive materials.[24]

Sections of the statute directed at movement were for relative speeds which exceeded the pace of Melbourne’s cable trams. Legal preciseness made these laws difficult to enforce, prosecute and convict; hence authorities favoured the discretionary ‘furious’ and ‘negligent’ charges, often when working-class drivers’ actions resulted in chaos, traffic tie-ups or a collision.[25] When public safety was compromised and lives put at risk because a road-user failed to give the right-of-way, as Jack Proctor did in Bloomfield v. Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co., the driver could be convicted of ‘negligent’ driving.

‘Negligent’ driving applied to situations where a loss, injury or damage was predicted, potentially imminent or sustained. Paul Williams, in his examination of Victorian statutes, defined it as the ‘omission to do something which a reasonable man, guided upon those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs, would do, or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do’.[26] This definition underscores the discretionary element of the law, indicating that Proctor’s actions were not ‘reasonable’ because a ‘prudent’ man would have waited for the road to clear before proceeding. Because types of vehicles were not specified in the Act, moreover, all movable forms of transportation were able to be policed for ‘furious’ or ‘negligent’ behaviour. This allowed bicycles and motor-vehicles – for a time – to be controlled with existing legislation. Discretionary, all-encompassing laws were effective for controlling the working classes because few possessed the resources to challenge the charge; and, initially, this legislation was also effective in controlling the motor-vehicles of the more affluent and powerful. However, as the number of motorised vehicles grew, speeds increased and crashes became more frequent, Melburnians demanded change.

Although motorists attracted media attention, traditional modes of transport continued to cause problems too. Throughout 1903, 1904 and into 1905, motoring infractions featured in newspaper stories, but other forms of road transport were also responsible for creating disturbances and injuring or killing road-users. On 22 October 1904 at approximately 9:20 pm, a man was struck by the poles protruding from a timber jinker[27] when he crossed the street in Richmond. Mr Seymour, a witness, saw the prostrate, unconscious man and called out for the three men aboard to stop; one shouted back, ‘Let him lay there.’ Seymour estimated the speed of the jinker at 12 mph, but could describe neither the jinker nor the men.[28] The driver of the jinker escaped. In September 1903, police summoned a fire cart for ‘furious’ driving, shouting, being a disturbance and creating a hazard at the intersection of Collins and Elizabeth streets.[29] Robert Hodges, a cyclist, was charged with negligent riding in Prahran Court on 23 February 1904 after he collided with Edgar Thomas and injured him.[30] Also in February, Mary Ann Ridley was killed in Carlton in a vehicle collision at the intersections of Elgin and Lygon Streets when she was thrown from the light cart in which she was riding.[31] In the same newspaper article, Margaret Hartnett was killed when she fell out of a hackney cab at the corner of Spencer and La Trobe streets. Even city employees were not immune from road crashes. On Barwise Street in North Melbourne in early 1904, Jeremiah Sullivan irresponsibly rode a dray-horse – bareback and fitted with blinders – near the railway, which took fright when a train passed. The horse crashed into a waggon destined for the Ascot races carrying eight passengers. The driver, George Dempster, sustained injuries to his back and ribs when the waggon overturned, which forced him to be absent from work for four weeks.[32] As he possessed the financial means, he launched a civil suit against the city on 12 August 1904. The judge ruled that Sullivan had failed to exercise sufficient care, and stated that his action was negligent; he granted Dempster £72 compensation for injuries and work absence.[33] Because of Dempster’s success, other passengers also filed claims, but the judge ruled against the plaintiffs Joseph and Abraham Davis for one of three possible reasons or a combination thereof: 1) the claim was too high; 2) neither had been injured; 3) or sustained loss.[34] Lastly, on 9 March 1905, thirteen-year-old Ethel Donnison was killed by a tram near the intersection of Lonsdale and Elizabeth Streets when she moved out of the path of an oncoming cyclist; she inadvertently slipped on the tracks and was run down.[35]

This snapshot of early-twentieth-century road mayhem reminds us that streets were already dangerous places, even without the advent of the motor-car. To some extent, the novelty and greater speed of the new machine only exacerbated existing issues of road safety.

Up until the 1880s, traditional modes of transport rarely exceeded a walking pace. Then, in the fifty years to 1930, with the arrival of bicycles, cable trams and motor-cars, urban road speeds increased fourfold. With these new transport modes came new definitions of ‘speeding’, as the benefits of faster travelling were realised (see figure below). Thus the tension between public safety and the individual motorist’s enjoyment of reduced travel times and the opportunity to cover greater distances existed at the outset, and complicated the creation of restrictive regulations.

Urban Road Speeds 1880-1925. Source: JD Keating, Mind the curve!: a history of cable trams, Transit Australia Publishing, Sydney, 1996, p. 106; JW Knott, ‘Road traffic accidents in New South Wales, 1881-1991’, Australian Economic History Review, vol. 34, no. 2, 1994, p. 84; C McShane & J Tarr, ‘The decline of the urban horses in American cities’, The Journal of Transport History, series 3, vol. 24, no. 2, 2003, p. 179; I Manning, Beyond walking distance: the gains from speed in Australian urban Travel, Urban Research Unit, Australian National University, distributed by Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1984, p. 20. As Manning indicates, it is difficult to substantiate average speeds for motor-cars as their speeds were dependent on driver preference: some drove conservatively while others accepted risk and put their ‘foot down’. Thus, the averages are deduced from a wide range of primary documents.

Motoring injuries and deaths also made the news because frustrated authorities realised the growing inability of the police to control the ‘horseless carriage’. On 5 May 1904, Arthur Gaj became Melbourne’s first motoring fatality; on St Kilda Road the wheel of his speeding motor-tricycle caught in the tram track and ‘shook his nerve’, throwing him from the machine. One eyewitness estimated that Gaj was travelling between 24 and 25 mph. The police also recognised their inability to exercise effective control. ‘They simply smile at us as they rattle by’, said the constable, ‘and we cannot catch them’. Constable James Tonkin stated during the Coroner’s inquest, ‘I say that 25 miles an hour is altogether too fast to travel. A driver can be summoned [sic] for furious driving. It is very difficult to stop a motor car.’ In his report the Coroner recommended that motor-car regulations be put in place, ‘in the interests, not only of the public, but of the motorists themselves’.[38] A hit-and-run crash between a yellow motor-car and a cyclist in 1906 brought renewed calls for accountability and the police were again accused of incompetence.[39] Police, as front-line workers, were unable to maintain public safety because of the motor-car’s potential speed, and the legal unaccountability of some drivers.

Prior to 1905, motor-cars in Victoria numbered less than a few hundred,[40] but although motoring was in its pioneering years, its impact and predicted benefits were receiving ample press. In response to British parliamentary debates and the draft of their Motor Car Bill, Melbourne was ‘abuzz’ with the new technology. In London, as reported in the Melbourne Argus in April 1903, Henry Norman predicted that rural people’s living domicile would expand from twelve miles to thirty, that decreased numbers of horses’ hooves would allow roads to be in better ‘nick’ and that London would no longer have to export 5000 tons of manure daily. In the same newspaper, the London Car Road Company estimated the replacement of 5000 horses with 500 motor-buses.[41] A May 1903 report from New York, also in the Argus, described the benefits of motor-omnibuses built by the London General Omnibus Company: the buses generated their own heat and light, carried thirty-two passengers on two levels and achieved speeds of 12 mph.[42] In Paris, France, also in May 1903, the automobile club conducted tests, comparing the horse and the motor-car; the test evaluated speed, braking and manoeuvrability – ‘and the motor vehicle out performed the horse at every turn’.[43] Some readers believed it was only a matter of time before personal motor-cars were a real possibility.

Yet not all media reports were positive. Many traditional road-users experienced the inconvenience of the transition and loss of autonomy. Letters to the editor of local newspapers, witness accounts in reported court cases, traffic professionals’ recommendations, and letters to public authorities exerted pressure for more comprehensive motor-vehicle regulations during the first decade of the century. On 22 January 1904, for example, a letter to the Argus lobbied for regulations of motor-vehicles, as they were scaring horses. At a minimum, the author wrote, the law should require motorists to give an audible warning, or signal their approach, as horses were often startled by a passing motor-car.[44] A letter of 10 November 1904 stated that narrow farm roads should be closed to motor-cars: ‘ protection ‘, the author stated; ‘even the quietest of farm horses fail to grow accustomed to the puffing and trumpet-blasting road monster that now claims full right of the road’.[45] Russell Grimwade, a pioneering Melbourne motorist, recounted an early motoring story of a car travelling on the main road from Mordialloc to Frankston which honked to warn cricketers playing on the roadway; the driver honked again to alert an approaching jinker with a family aboard. Startled, the father yanked the reins, causing a child to fall off and consequently the child’s leg was run over. A doctor riding in the motor-car took the child into a nearby tent to examine it, amidst great hostility. He and the other motorists made a hasty retreat, however, when a livid elderly woman ‘stormed off’ to get a butcher knife with the intent of attacking the motor-car’s tyres.[46]

Not surprisingly, the prospect of increased regulation for motorists met with formal and organised resistance. Also on the letters page of the Argus of 22 January 1904 was correspondence from Harry James (Advertising Manager, Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co.), founder and acting Honourable Secretary of the ACV (Automobile Club of Victoria), who stated that motor-cars were easier to handle at higher speeds, and this was precisely why the 1903 British Motor Car Act set the speed limit at 20 mph. He continued, that some motorists see horses as ‘stupid uncontrollable beasts that ought to know better than go rearing up and prancing about the road at the sight of any unfamiliar object’, and concluded by stating that the new club’s purpose was to conform to, and obey traffic regulations and to assist drivers of ‘fractious horses’.[47] The letter not only reflected a conflict between traditional and modern road-users; its tone indicated that motoring gentlemen felt themselves perfectly capable both of policing themselves and coming to the assistance of those relying on obstreperous animals. No doubt James was also expressing his ill feelings after losing the civil suit in 1902.

On 20 February 1904, the ACV made its inaugural run, with thirty motor-cars and several motor-cycles taking the drive. Motoring, as a recreational pursuit of the affluent in the early part of the twentieth century, attracted some of Melbourne’s most prominent figures. Present for the day’s gala event were Sir Samuel Gillott, Chief Secretary of the State parliament and former Melbourne mayor; several Melbourne city councillors; the city’s town clerk, John Clayton and surveyor, AC Mountain; St Kilda’s mayor, John H Pittard, JP and town clerk, John N Browne; and several other prominent citizens.[48] Chief Justice John Madden was the ACV’s first president, and in 1904 became the Lieutenant-Governor of Victoria.[49] This relationship between Melbourne motorists and Victoria’s politicians continued: in August 1905, during the Motor Car Bill debates, the ACV wrote to Thomas O’Callaghan, Chief Commissioner of Police, informing him of the intended route of their promotional ride, in order that ‘members of the State Parliament’ could have ‘an opportunity of witnessing the facility with which motor cars can be driven & controlled’. The event ‘passed off quietly’.[50] Ironically, it was Sir Samuel Gillott who spearheaded Victoria ‘s 1905 Motor-Car Bill.

The Motor-Car Bill of 1905

By June 1904 the Melbourne Council of the Municipal Association had met in an attempt to regulate the speed of both motor-cars and motor-cycles. Each member had a copy of the 1903 Imperial Motor Car Act. The ACV offered to provide counsel to the Municipal Association, and Councillor WH Allard (Brighton) suggested that proceedings should not commence until this was done. Allard stated further that Brighton Council had set speed limits of 10 mph, with 5 mph over crossings; also, with some motoring experience he did not hesitate to say that a motor-car was much easier to handle at 25 mph than a horse at 10 mph. He felt that safety would be ensured if speed limits were set at 15 mph, with 5 mph over crossings and 30 mph on streets away from general traffic. Councillor George L Skinner (Prahran) stated, ‘our primary duty is to protect the public’. Consequently, a sub-committee was set up to draft a uniform set of regulations.[51] In August the sub-committee reported that the Imperial legislation should be adopted, with the following changes: councils should not be responsible for putting up warning signs; the minimum age for an automobile or motor-cycle licence should be seventeen; the maximum speed limit should be twenty-five miles per hour; and motor-cars should be required to stop when horses were present to maintain public order. Although councils were responsible for the road itself, legislation would have to be executed at the State level, as local councils were not responsible for regulating traffic.[52]

In January 1905, motor-car legislation moved to the forefront of the Municipal Council’s agenda. In addition to the sub-committee’s recommendations, increased public pressure from council constituents and letters to the press further motivated the authorities to draft and implement new regulations. In response to an obstinate State Parliament, Melbourne’s town clerk, John Clayton, on 7 January 1905, requested JC Stewart, the City Solicitor, to submit legal advice; he also requested information about present statutes that could make the registration of motor-cars and the licensing of drivers mandatory, and called for the English Motor Car Act to be examined. Stewart replied and recommended that a statute similar to the English Motor Car Act be put into place; again, this required implementation at the State level.[53] An article in the Argus on 6 January 1905 reported that Chief Commissioner O’Callaghan had consulted with Sir Samuel Gillott, whose office was responsible for the police, concerning the high speeds of motor-vehicles and the loss of autonomy many other road-users felt. O’Callaghan reminded the Chief Secretary that the existing regulations had been put in place to deal with street traffic travelling at half the speed of motor-vehicles. He also noted that, in the beginning, motor-cars were so few that constables could easily recognise the driver; however, these vehicles now numbered in the hundreds, and ‘… many of them [were] indistinguishable one from another in the fleeting glimpse that is usually afforded the policeman and the drivers are frequently muffled up with coats, goggles, masks, and caps of a uniform pattern’. Identifying numbers were at the forefront of requests because of the unaccountability of some rogue drivers; this also had the potential of shoring up relations between the motoring fraternity and the wider community by demonstrating that only a few ‘rotten apples’ existed among the motorists.[54]

Speed limits presented a more complicated problem because many motorists saw this as an infringement of their civil liberties and felt that the individual should be left to judge the ‘common danger’ of the road. In towns and cities they might drive only a few miles an hour, but on the open road they wanted to be free to travel at much higher speeds.[55] Speed limits, they argued, would only serve to create criminals out of ordinary motorists; rather, motorists wanted to police their own driving.[56] In the latter part of January 1905, a memo to the Lord Mayor of Melbourne from the ACV—as the motoring body of Victoria—requested that the Municipal Council consult with them.[57] Four days later—possibly because of a non-response—a public letter to the Lord Mayor from the ACV stated that motor-cars were here to stay—but that regulations were considered to be premature.[58]

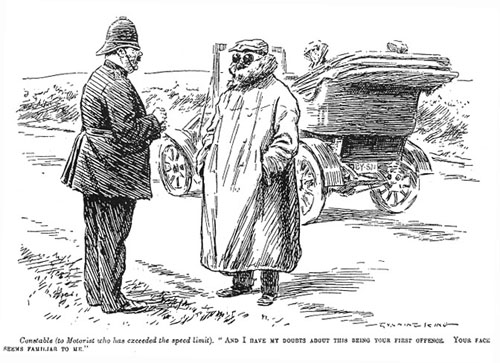

Constable (to Motorist who has exceeded the speed limit). ‘And I have my doubts about this being your first offence. Your face seems familiar to me’. Source : A-J Doran (ed.), The Punch cartoon album: 150 years of classic cartoons, Grafton, London, 1990, p. 36 (c. 1905).

Between January and July 1905, before Sir Samuel Gillott introduced the Motor Car Bill into State Parliament, motor-cars continued to make news. In February 1905, Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. showcased motoring by running the first Dunlop Reliability Race between Melbourne and Sydney; 16 of the 23 motor-cars finished the four-day event, and nine had perfect scores. An additional non-stop return run to Ballarat decided the winners.[59] On 7 April 1905, E Norton Grimwade attracted considerable interest when he appeared in the District Court for ‘furious’ driving. Driving his motor-car along St Kilda Road, he passed a tram and proceeded to his home in Central Melbourne, unaware of any public safety breach. Young Constable Thomas Weibye (No. 5065)—26 years old and two years a constable—gave pursuit on his bicycle and, catching up to Grimwade, demanded his name and address.[60] When Grimwade refused to divulge this information, Weibye followed him to Flinders Lane where he ascertained the necessary details. Several people on the tram corroborated Constable Weibye’s story, estimating the car’s speed at 20 mph; each witness used the cable tram’s speed as the relative measurement of safety. James Grant, gripman in the employ of the Tramway Company said: ‘I saw a motor-car go past the tram I was on in St. Kilda Road opposite the Barracks. It was going twice as fast as the tram.’ Charles H Edwards, conductor on the same tram, provided supporting evidence. Appearing for the defendant, Harley Tarrant, a motoring authority, prominent Melbourne entrepreneur and owner of the Tarrant Motor and Engineering Company, stated that Grimwade’s car was incapable of 20 mph owing to a malfunction; despite this, Grimwade was found guilty and charged 10/- and £2-16-0 costs.[61] Public safety itself was in fact a secondary concern: it was the breach of public order that provided the impetus for legal action.

In April 1905, a report in the automobile section of Melbourne Punch stated that lorries and fast-moving drays were refusing to yield to motor-cars, and that motorists were being unjustly prosecuted because they were forced to drive on the wrong side of the road to pass. Phaeton, the author, wrote: ‘Motorists should seize every opportunity of drawing the attention of the police to their duties in this connection, and in time a better state of things is sure to prevail.’[62] On 9 May 1905, a sensational story from London reported a charge of manslaughter against a chauffeur who had run down and killed a child. The Daily Mail offered a reward of £100 for the capture of the ‘hit and run’ driver. This reward was discreetly withdrawn, however, when it was discovered that the Italian chauffeur, Cornalbas, was employed by Hildebrand Harmsworth, the younger brother of Lord Alfred Harmsworth—the proprietor of the Daily Mail .[63] Melbourne motorists were spurred into action to ensure that regulation in Victoria remained fair. Premier Bent felt unable to ignore Melbourne’s motoring problem any longer; in May 1905 he announced the State Government’s intention to purchase a motor-car for police in an attempt to control speeding motorists and alleviate some of the bias towards motoring.[64] In July 1905, Sir Samuel Gillott, as Chief Secretary, introduced the Motor-Car Bill into State Parliament.

Issues of class pervaded Victoria’s Motor-Car Debates. Alfred S Bailes, member for Sandhurst (Bendigo), questioned whether, if a man should be rich enough to own a £1000 motor-car, he should be allowed to do as he liked? James A Boyd, member for Melbourne, stated that the Chief Secretary believed that every motor-car was ‘worse than a bomb out of a Japanese Gun’, and argued: ‘Surely the fact that the vehicle belonged to the man, and that if any damage was done he would suffer, would be a sufficient deterrent’.[65] Boyd’s assertion supported the idea that civil liability would suffice in cases where a loss was sustained, as in Bloomfield v. Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. However, legal recourse was far beyond the means of most working-class road-users. Legal costs paid by Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. were approximately £250 – at a time when most ‘blue-collar’ workers earned only a few pounds a week.[66]

Moreover, the possibility of police constables demanding a motoring gentleman’s licence sparked significant debate. David Gaunson, the representative of Public Officers, discussed at some length the potential increase in police powers. What if the motorist had forgotten his licence? How long would he have to produce the licence? Members of parliament agreed that only constables in uniform would have the power to request licences and registration. Speed limits were the last major issue, and the Chief Secretary was willing to allow higher speeds in Victoria than those set in Britain because of significantly lower population densities and greater area, especially in the country. Yet, the speed limits in Britain had been generous when set at two to three times the rate of traditional modes of transport. William H Irvine, member for Lowan, summarised the feelings of those who believed regulations were a necessity when he stated that ‘motor cars should not be allowed to monopolise the roads’.[67] Irvine’s words also affirmed that motor-traffic had to be successfully integrated with other forms of road transportation.

Motoring lobby groups proved resourceful and powerful, and in the winter of 1905, when parliament was putting the final touches to the Motor-Car Bill, 47 year-old Thomas Hall, an irondress working at Messrs J and T Muir’s iron foundry, became the first motor-car fatality.[68] On 24 August, while crossing the intersection of Nicholson and Gertrude Streets in Fitzroy, Hall was struck by a southbound automobile driven by Macpherson Robertson. His body was picked up and driven to the hospital in Robertson’s vehicle – a common occurrence during the early years of motoring – but he was declared dead upon arrival.[69] The Motor-Car Bill failed before its third reading and was shelved.[70]

Motoring interest groups had exerted a great deal of political pressure on State politicians, and consequently the 1905 Motor-Car Bill was thrown out. The ACV’s annual report for the 1905-6 seasons stated: ‘In many respects the provisions as originally presented, were of a somewhat drastic character. … It is to be hoped that at no very distant date rational legislation will be introduced to bring all parts of the State under one set of motor laws’.[71] The issue at stake was one of civil liberties: motorists disputed the requirement to be licensed, being forced to display number plates on their motor-cars, and having to adhere to ‘somewhat’ arbitrary speed limits. Russell Grimwade, in his draft account of early motoring, described the events:

Also, well remembered is the resentment a few years earlier of the few car owners of that day to the proposal of the State Government that motor cars be registered and forced to carry an identifying number. Those hardy pioneers resented with great vehemence the suggestion that their poor little machines be put under police supervision and made to carry a conspicuous number whilst private horse-drawn carriages were free of such labels, and who was to examine, as was suggested, the competency of the would be drivers to handle a car?[72]

Upper-class motorists were appalled at the idea that they would be under the supervision of working-class police constables. They also argued that it was unfair to have, essentially, one law for the motorist and another for users of traditional modes of transport.[73] Only hackney cabs and commercial vehicles required number plates, and these were driven by working-class people – usually men. They also pointed out that the number of motor-cars was small, most drivers behaved responsibly, and the discretionary application of the Police Offences Act had been effective in controlling existing problems. For example, in August 1905, during the Motor-Car Bill debates, James A Boyd, member for Melbourne, stated: ‘there were reports in the newspapers showing that convictions had been obtained during the last few days against motor drivers for furious driving. That showed that the existing law was sufficient to regulate the speed of motor cars as in the case of all other classes of vehicle’.[74] In 1905, Victoria was as yet unprepared for this transition to increased powers for police and accountability of wealthy and influential motorists.

Conclusions

A cartoon in the Australian Bulletin, 6 July 1905, entitled ‘Keeping Order’ (see illustration below) encapsulated the problem of motor-cars on Melbourne’s streets. It underscored the loss of autonomy many road-users felt when faced with a fast-moving motor-car, but also argued that a police motor-car was not the solution, and would only exacerbate issues of compromised road safety and order. Today motorists – by and large – conform, obey and fulfil the many regulations and obligations that are part of owning and driving a motor-vehicle, but at the outset of the twentieth century licensing, number plates and speed limits were seen as huge infringements of motorists’ liberties – especially when these were not required for private carriages.

'Keeping Order. Premier Bent has decided to supply the Melbourne police with a motor car, so that when they see a motorist going too fast and endangering the public safety they can overtake him by going faster still. And when the offender puts on an extra spurt, and the police put on another extra spurt, and they both spurt some more, things will happen.' Source : ‘Keeping order’, Australian Bulletin, 6 July 1905, p. 12.

In 1908 Sir Alexander Peacock successfully passed the Motor-Car Bill into law. However, the Victorian Motor-Car Act 1909, which became effective in 1910, omitted a fixed speed limit, which was one of the stipulations that allowed the Bill to become law. The legislation did allow local councils and shires to set speed limits, and many of them did.[75]

Even though motorists became the most regulated group in Western society between 1905 and 1950, they have remained a powerful lobby group. But despite all the regulations and penalties, effective measures have not been found to eliminate speeding[76] or to reduce the relative number of collisions.[77] And ironically, pedestrians may be the road-user group most in need of regulation, policing and education – in Melbourne, as in other motorised cities.[78] Although we have come a long way since Sir Samuel Gillott’s myopic statement that ‘a pedestrian has just as much right to walk in the middle of the road as he has to walk on the footpath’,[79] it seems we still have a long way to go to eliminate ‘furious’ and ‘negligent’ driving.

Endnotes

[1] The author would like to thank David Philips and Andy Brown-May for reading drafts of this paper and providing insightful and valuable feedback, which vastly improved the final product. Gratitude and appreciation are extended also to Public Record Office Victoria and its online journal, Provenance, who have amiably and courteously allowed this article to be reproduced by the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria.

[2] Victoria Government Gazette, vol. CXII, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1900, p. 4231 (Costs – Special scale – ‘Rules of the Supreme Court 1900’ – Order LXV, r. 29 – Appendix N. – Discretion of Judge to allow costs on ordinary scale). The suit was for £499 because any amount under £500 could make a claim for court costs and fees, which were approximately £70, or six months salary for a working-class person.

[3] ‘Racehorse v. Motor-Car: Novel Lawsuit: Bloomfield v. Dunlop Tire Co.: £250 Damages and Costs’, The Australian Cyclist and Motor Car World, 1 May 1902, pp. 1-2; Bloomfield v. The Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. Ltd. (1902) 8 “The Argus” Law Reports 103; Bloomfield v. The Dunlop Tyre Company Limited (1902-3) 28 Victorian Law Reports 74; ‘Motor-car accident: £250 damages awarded’, Argus, 24 April 1902, p. 7; ‘Motor-car accident: £250 damages awarded’, Age, 24 April 1902, p. 6. Some historians have claimed that Bloomfield v. Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. was charged under the notorious ‘Red Flag Law’ (see below), but Victoria’s Traction Engines on Highways Act (1900) specifically states in Section 2: ‘and shall not apply to motors used on tram or rail lines or motor cars or cycles’. Recounting the story almost fifty years later, Jack Proctor too believed he had been charged for breaching the ‘Red Flag’. See ‘Foundation members honored: stories of early motoring days: “Mr. W.J. Proctor and the Red Flag”‘, The Radiator, 18 June 1947, p. 3, in the Grimwade Collection, 3rd Acc., Series 13, Item 13/13 – 15/2, Box 9, University of Melbourne Archives.

[4] ‘Automobilism’ is defined as the motorists’ belief that they have the unfettered right to use the roadway and police their own driving behaviour: see G Davison & S Yelland, Car wars: how the car won our hearts and conquered our cities, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2004, p. 117. This attitude, at the turn of the twenty-first century, manifests itself in behaviours such as aggressive driving or ‘Road Rage’; conducting a multitude of distracting and dangerous activities while driving, for example reading and sending text messages on a mobile phone; and speeding. Blatantly dangerous driving behaviours are not new, of course; they began when ‘men’ sat behind the wheel of the first self-propelled agricultural and industrial machines.

[5] SE Davies, ‘Vagrancy and the Victorians: the social construction of the vagrant in Melbourne, 1880-1907’, PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 1990, p. 122; An Act for regulating Hackney and Stage Carriages in and near London 1843 (C. 86) (UK).

[6] An Act for regulating the Use of Locomotives on Turnpike and other Roads, and the Tolls to be levied on such Locomotives and on the Waggons and Carriages drawn or propelled by the same 1861 (C. 70) (UK); 1865 (C. 83) (An Act for further regulating the Use of Locomotives on Turnpike and other Roads for agricultural and other Purposes).

[7] Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency, History of motoring and licensing in Britain: the early years, 28 January 2003, <http://www.dvla.gov.uk/histm_l/earlyday.htm>, viewed 14 June 2004.

[8] An Act to amend the Law with respect to the Use of Locomotives on Highways 1896 (Ch. 36) (UK).

[9] ‘Re: Furious driving – Henry George Allendale’, London Times, 18 April 1903, p. 5.

[10] Hackney and Carriage Act 1843 (UK), s. xxviii; Parliamentary debates (UK), 4th ser., vol. 121, 27 April 1903, p. 467.

[11] ibid., p. 470.

[12] In fact, bicycles and motor-cars were increasing urban road speeds to almost 15 mph, but it would be some years before urbanites adjusted.

[13] For a discussion of English motor-cars and policing, see C Emsley, ‘”Mother, what did policemen do when there weren’t any motors?”: the law, the police and the regulation of motor traffic in England, 1900-1939’, Historical Journal, vol. 36, no. 2, 1993, p. 368. In Victoria, after the 1909 Motor Car Act became law, police also found it difficult to prosecute speeding motorists in court: see PROV, VA 724 Victorian Police, VPRS 807/P000 Inward Correspondence, Unit 412, File H11125 (Memo: Re: remarks made by magistrates on the police method of timing motor cars, 19 November 1910); VPRS 807/P000, Unit 388 (Memo: Re application of Constable Rose 4297 for a stopwatch for timing fast driven motor cars, February 1910).

[14] Mayhew v. Sutton (1901) 71 LJR 46.

[15] Smith v. Boon (1901) 49 WR 480; 84 LT 593; ‘Smith v. Boon’, London Times, 4 May 1901; Mayhew v. Sutton (1901) (UK).

[16] An Act to amend the Locomotives on Highways Act 1903 (C. 36) (UK) s. 1 (1).

[17] ‘Motor cars: Imperial legislation – London July 8’, Argus, 9 July 1903, p. 5; Emsley, p. 365; Motor Car Bill Debates, vol. 127, Government Printer, London, 1903, p. 1007.

[18] Debates, vol. 127, p. 519.

[19] Emsley, p. 368.

[20] Report of the British Royal Commission on Motor Cars, vol. XLVIII, Command Papers 3080, Government Printer, London, 1906, p. 25.

[21] D Philips, ‘Law’, in G Davison, JW McCarty & A McLeary (eds), Australians 1888, Fairfax, Syme & Welson Associates, Broadway, NSW, 1987, p. 370.

[22] An Act to regulate the Traffic of Traction Engines 1900 (Act No. 1693), s.2. See also note 3 above.

[23] An Act to consolidate the Law relating to the Management of Towns and other Populous Places and for the Suppression of various Offences: Police Offences Act 1890 (Act No. 1126), s.5 (xvii).

[24] loc. cit.

[25] Cf. British Royal Commission on Motor Cars, p. 47. Recommendation II – abolition of the 20 mph speed limit – resulted from its minimal use, and most offences carried the discretionary charge of Section 1 in the 1903 Imperial Motor Car Act.

[26] P Williams & H G Joseph, The Police Offences Acts including The Police Offence Act 1890, The Police Offences Act 1891, The Police Offences Act 1907, The Animals Protection Act 1890, The Lotteries Gaming and Betting Act 1906 together with The Street Betting Suppression Act 1896, The Sports Betting Suppression Act 1901, The Public Meetings Act 1906, Charles F. Maxwell (G. Partridge & Co.), Melbourne, 1908, p. 75.

[27] P Cuffley, Buggies and horse-drawn vehicles in Australia, Five Mile Press, Fitzroy, Vic., 1988; J Badger, Australian horse-drawn vehicles, Rigby, Adelaide, 1977. A jinker is a horse-drawn waggon designed to transport logs, poles or other timber. The timber is suspended under a high frame with chains, rather than loaded onto a waggon deck. A common jinker was a two-wheeled cart capable of carrying two or three people.

[28] VPRS 807/P0, Unit 204, File 8287 (Report of Sergeant FP Meagher 4850 of Negligent Driving, 22 October 1904).

[29] ‘Police and firemen: “furious driving and violent outcry”‘, Argus, 24 September 1903, p. 5.

[30] ‘A careless cyclist’, Argus, 23 February 1904, p. 7.

[31] ‘Casualties and fatalities’, Argus, 20 February 1904, p. 19.

[32] VPRS 3181/PO Town Clerk’s Files, Series I, Unit 514, File 660 (Claim of Cole & Morris, 19 February 1904); VPRS 3181/P0, Unit 514, File 2859 (Letter from the City Solicitor to Town Clerk; Re: Cole & Morris, 19 February 1904).

[33] ‘Re: Crash of Jeremiah Sullivan – city employee’, Age, 12 August 1904 (in VPRS 3181/P0, Unit 514).

[34] ‘Re: Crash of Jeremiah Sullivan – city employee’, Age, 15 October 1904 (in VPRS 3181/P0, Unit 514; VPRS 3181/P0, Unit 514, File 996 (overturning of a cab in Macaulay Road said to have been caused by negligence of Council’s employee, 22 August 1904).

[35] VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 786, File 1905/282 (Coroner’s inquest into death of Ethel Donnison, 9 March 1905); ‘Child killed in Elizabeth Street: knocked down by tram’, Argus, 10 March 1905, p. 6.

[36] For the impact of the railway on understandings of speed, time and space see W Schivelbusch, The railway journey: the industrialization of time and space in the 19th century, Berg, Leamington Spa, 1986.

[37] JB Jacobs, Drunk driving: an American dilemma, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1989, pp. 15-26 passim.

[38] ‘High speed motoring: the St. Kilda-Road fatality’, Age, 6 May 1904 (in VPRS 3181/P0, Unit 74; VPRS 24/P0, Unit 775, File 1904/435, Coroner’s Inquest Arthur Gaj, 10 May 1904. Discrepancy exists concerning Arthur Gaj’s surname in the Coroner’s report.

[39] ‘Motor car speed in the city: Mr. Adams’s condition serious: the yellow car not found’, Age, 15 December 1906 (in VPRS 3181/P0, Unit 75).

[40] S Priestley, The crown of the road: the story of the RACV, Macmillan, South Melbourne, 1983), pp. 1-23 passim.

[41] ‘The coming of the motor: a remarkable forecast’, Argus, 11 April 1903, p. 5; ‘The motor in London: superseding horses – London, April 10’, Argus, 11 April 1903, p. 18.

[42] ‘New motor omnibuses: New York, April 2’, Argus, 9 May 1903, p. 5.

[43] ‘Automobile v. Horse (Daily Mail) Paris, May 12’, Argus, 20 June 1903, p. 4.

[44] ‘Motor car traffic’, Argus, 22 January 1904, p. 7 (letter to the editor).

[45] ‘The motor car scare’, Argus, 10 November 1904, p. 10 (letter to the editor).

[46] R Grimwade, ‘Early Motoring in Victoria’, draft typescript, c. 1944, Grimwade Collection, 3rd Acc., Series 13, Item 13/1-13/2, Box 8, University of Melbourne Archives, p. 4.

[47] ‘Motor car traffic’, Argus, 22 January 1904, p. 7 (letter to the editor).

[48] ‘Motoring’, Argus, 20 February 1904, 18.

[49] Priestley, p. 9.

[50] VPRS 807/P0, Unit 269, File X7281 (letter dated 22 August 1905).

[51] ‘Motor-car regulations: proposed regulations’, Argus, 15 June 1904, p. 4.

[52] ‘Motor cars and cycles: legislative regulation suggested’, Argus, 10 August 1904, p. 5.

[53] VPRS 3181/P0, Unit 514 (Statement of Costs; Re: Motor Cars – from City Solicitor to Town Clerk, 6 January 1905).

[54] ‘Motor traffic: necessity for regulation’, Argus, 6 January 1905, p. 5.

[55] ‘Control of motor traffic’, Argus, 16 April 1907 (letter to the editor; in VPRS 3181/P0, Unit 76).

[56] For a view of ‘automobilism’ from South Australia in 1915, see FA Munsey, ‘The South Australian motor: the speed limit’, Munsey’s Magazine, 1 June 1915 (in VPRS 807/P0, Unit 556, File S7443).

[57] Royal Automobile Club of Victoria Archive, Memo: Re. Motor Regulations to Melbourne’s Lord Mayor signed by Harry James – Acting Honorary Secretary, 21 January 1905.

[58] ‘Motor car traffic: request to Lord Mayor’, Argus, 25 January 1905, p. 9.

[59] ‘Motoring: Dunlop Reliability Race’, Argus, 22 February 1905, p. 5.

[60] Victorian Police Gazette, J. Kemp, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1905, p. 24.

[61] R Haldane, The people’s force: a history of the Victoria Police, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 1986, p. 135; ‘A motor driver fined’, Argus, 7 April 1905, p. 6. Tarrant’s Garage had a waiting room for chauffeurs with a billiard table where they could amuse themselves while their owner’s car was being repaired.

[62] ‘Motor notes’, Melbourne Punch, 26 April 1905, p. 526.

[63] ‘A chauffeur’s arrest: remarkable case London, May 9’, Argus 10 May 1905, p. 7.

[64] ‘Motor notes’, Melbourne Punch, 11 May 1905, p. 630.

[65] Parliamentary debates (Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly, Vic.), Session 1905, vol. 110, p. 1295.

[66] ‘Foundation members honored’, p. 3; VPRS 807/P0, Unit 2, File 5973 (monthly summary of salaries and wages: Western District, 23 June 1909); Haldane, p. 134.

[67] Parliamentary debates (Vic.), Session 1905, vol. 110, p. 1305.

[68] Arthur Gaj was the first motoring fatality in 2904, whereas Thomas Hall, struck and killed by a motor-car, was arguably the first motor-car fatality in the city. In January 1905, Samuel Payne of Kew was killed at the intersection of Albert and Evelyn Streets in East Melbourne when his bicycle struck the rear portion of a motor-car driven by FH Hutchings, but the Coroner blamed Payne for the collision; therefore, it is questionable if this can be labelled the first motor-vehicle fatality. See VPRS 24/P0, Unit 784, File 1905/27 (Coroner’s Inquest in the Death of Samuel Payne, 4 January 1905); ‘Motor-car collision: a cyclist killed’, Argus, 5 January 1905, p. 5.

[69] VPRS 24/P0, Unit 793, File 1905/992 (Coronor’s Inquest into Death of T.J. Hall, 24 August 1905); ‘Motor car fatality: man knocked down and killed’, Argus, 25 August 1905, p. 5; ‘Motor-car fatality: coroner’s inquest opened’, Argus, 28 August 1905, p. 6.

[70] The impetus for the Motor Car Bill was not crashes and deaths caused by the motor-car because the streets and roadways, with their traditional modes of transport, were dangerous places already. Rather, it was the potentially exorbitant speeds of motor vehicles and the loss of autonomy this caused other road users.

[71] Royal Automobile Club of Victoria Archive, Annual Report, Automobile Club of Victoria, Melbourne, 1905.

[72] ‘Early Motoring in Victoria’, p. 2. For various reasons, Grimwade’s statement might have been less ‘cheeky’ had it been written during the winter of 1905.

[73] Haldane, p. 132; D Wilson, ‘On the beat: police work in Melbourne, 1853-1923’, PhD thesis, Monash University, 2000, p. 180.

[74] Parliamentary debates (Vic.), Session 1905, vol. 111, p. 1346.

[75] Between 1910 and 1912, on account of court challenges and biased magistrates, a procedural change was introduced for the policing of speed limits: silver split-second stopwatches were purchased at £7.15.0 each; distances were measured by a surveyor; and two constables were required to do the timing. For council and shire speed limits see LL.B. E. Roy Burgess, The rules, regulations, by-laws, &c. of Victoria 1922-1924, The Law Book Company of Australasia Limited, Melbourne, 1925, pp. 268 & 286. For relative speeds see B Carroll, Getting around town: a history of urban transport in Australia, Cassell Australia, Stanmore, NSW, 1980, p. 94. See also JW Knott, ‘Speed, modernity and the motor car: the making of the 1909 Motor Traffic Act in New South Wales’, Australian Historical Studies, no. 103, 1994, pp. 2210-41 passim; An Act to regulate the use of Motor Cars 1909 (Act No. 2237), s. 15; Haldane, p. 137.

[76] Jacobs, pp. 23-5; CD Robinson, ‘Police and traffic law enforcement’, in KL Milte & TA Weber (eds), Police in Australia : Development, Functions, Procedures, Butterworths, Sydney, 1977, pp. 338-40.

[77] Davison & Yelland, p. 62.

[78] A Brown-May, Melbourne street life: the itinerary of our days, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Kew, Vic., 1998, p. 62.

[79] Parliamentary debates (Vic.), Session 1905, vol. 110, p. 1148.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples