Author: Amber Graciana Evangelista

History curator and former PROV intern Amber Evangelista recently completed a project utilising the Victorian Female Prison Register.

Female prison registers

In early February 1855, Bridget Plunkett was sentenced to five years imprisonment for robbery. A quick reading of her prison record suggests she was not a woman of any particular historical significance. The 48-year-old servant was able to read (although she couldn't write) and had several petty crime charges against her name. At first glance, Plunkett’s story does not seem to be of any huge historical significance. However, ‘No 1’ is carefully inked across the top edge of her record. Plunkett just so happened to be the first of many women to be recorded in the first volume of the Victorian Female Prison Register.

Created by the Penal and Gaols Branch, the Victorian Female Prison Register records the name and details of female prisoners in custody in Victorian gaols from 1855 onwards. From theft to murder, crimes of all natures are recorded in these remarkable volumes. Between 1855 and 1948, over 7000 women’s names were recorded in the registers held by Public Record Office Victoria. Of these, sixteen are now open to public viewing. In 2015, these were made accessible online.

Mugshots online

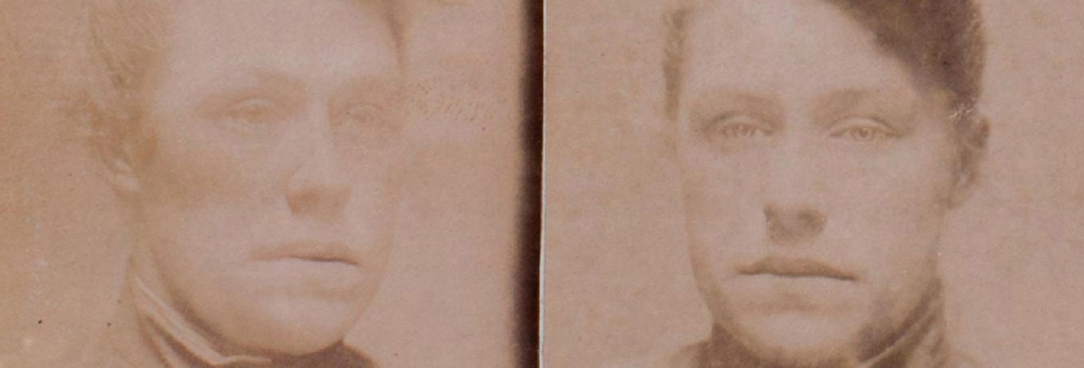

Having a bit of a penchant for crime and an interest in women’s history, I was thrilled that these records were made available for download. Having viewed some of the records at PROV, I knew that several hundred of the women’s records included mug shots. These stunning black and white photographs were incredibly evocative and offered a fascinating insight into the lives of the women within the register.

The volume of images is staggering: there are over 900 of these mugshots. Viewing them en-masse is quite an experience, and then downloading 900 images or 7,000 records is a bit laborious for most people so I wanted to create an easy means for people to view the mugshots and each woman’s story without having to download each individual record.

Together with a web developer we created an online space to display all 900 photographs. It's been a true labour of love (completed in the early hours before work!) and I'm thrilled to have finally seen it to completion.

Vagrants and murderesses

The project - named Vagrants and Murderesses- endeavours to humanise the women within the prison register records. In displaying all the photographs together it places a visual emphasis on the mugshots and encourages viewers to look a little beyond the women’s crimes. It also gives users more insight into their lives, allowing them to view each woman’s individual record.

We decided to take the project a step further by creating a searchable database that allows users to search for particular women and compare records. As well as being able to download the records in pdf form, PROV made the VEOs (VERS Encapsulated Objects, where digitized resources are stored by PROV in a special digital format) for the register available. This meant raw data from each record was available - including parts of each record that had been transcribed. This included date of birth, place of origin, their offense, occupation, religion, marital status as well as physical descriptions. Due to the online availability of these VEOs, this information is now available and searchable via Vagrants and Murderesses.

We also built a custom comparison function to allow users to compare different information from the register. The comparison tool gathers and compares the data from every women's record, allowing you to generate some fascinating findings. For example, if I want to find out the most common name and offense among the women, I learn that ‘Marys’ were regularly convicted for ‘vagrancy’! Or I can learn that within the register 'Ireland' was the most common-place of origin, 'vagrancy' the most common crime and 'servant' the most common occupation. There are also some hidden surprises in the mix: although the least common crime, ‘bigamy’ still appears 11 times!

The data comparison function is fascinating, but also incredibly sobering. It isn’t until the sheer numbers are in front of you that you begin to realise the scale of poverty and desperation behind the records. For instance, of the 7000 women, over 2000 were not fully literate. 1061 were unable to read or write, 800 could only read and 500 could only read a little. And in a time where you could be arrested for homelessness nearly 3000 of the women were arrested for vagrancy or insufficient means. Other offences reveal hidden parts of women’s lives in the 19th and 20th century: abortions, abandoned children, concealment of birth and alcoholism appear regularly. I hope that Vagrants and Murderesses better equips people to research these parts of women’s history.

The aim of Vagrants and Murderesses is to allow people to unearth the histories of women who didn’t make the history books: women who lived lives of poverty and crime. I hope Vagrants and Murderesses allows researchers to better understand the lives of the female criminals, beyond the famous poisoners and femme fatales.

Aside from this, it's also just a great research tool for family history researchers, historians and true crime enthusiasts. It is just in its early stages however, so please report any problems you have via the ‘about’ section of the site. I hope you enjoy using Vagrants and Murderesses and I’m very excited to see what findings people are able to generate, and what research and stories might emerge!

Vagrants and murderess can be found at: https://www.vagrantsandmurderesses.com/

Please credit Vagrants and Murderesses if you use any of the data collected or generated by our comparison search functions in your own work.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples