Author: Tara Oldfield

Senior Communications Advisor

As of the 27th of February, digital scans of the asylum patient records held in our collection are available to view on Ancestry. The collection contains more than 53,000 records digitised over three months by Ancestry. The asylums covered as part of the digitisation project include:

1. Ararat Asylum

2. Ballarat Asylum

3. Belmont / Glen Holme / Landcox Licensed Houses

4. Cloverdale Licensed House

5. Collingwood Asylum

6. Kew Asylum

7. Kew Cottages

8. Lara Inebriate Retreat

9. Merton Licensed House

10. Mont Park Hospital for the Insane

11. Mt Ida Licensed House

12. Northcote Inebriate Asylum

13. St Helens / Pleasant View Licensed House

14. The Tofts Licensed House

15. Yarra Bend Asylum

History of inebriate retreats

You'll notice a few inebriate retreats listed and may be wondering what they were, and how they were different from the insane asylums.

In the early to mid-1800s, Melbourne was described by Temperance activists as “The most drunken community on the face of the earth,”1 with consumption in Australia at an annual high point of 13.6 litres of pure alcohol per head (according to 1830s data).2

According to historian Susanne Davies in her paper The Search for a Certain Cure for Provenance:

“By the late nineteenth century, Victoria’s social reformers, politicians and doctors agreed that alcohol, or more specifically, some people’s propensity to over indulge in it, was the cause of inestimable harm.”

Habitual drunkenness previously seen as a sin or failure of a person’s character, became re-defined as a disease requiring medical intervention. In 1872 the Inebriates Act was introduced enabling the operating of Inebriate Retreats for the treatment of alcoholism.3

Anyone could apply to be taken in by an Inebriate Retreat through applications to the Master-in-Lunacy or to a judge, police magistrate or justice of the peace. And if a person was certified to be an inebriate by at least two medical practitioners, the Master-in-Lunacy, judge or police magistrate could have the subject apprehended and forced into treatment. The first Inebriate Retreat was the Northcote Inebriate Asylum.4

Northcote Inebriate Asylum

Records of patients from the Northcote Inebriate Asylum span from 1890 to 1892. The records list the date of patient’s previous admission (if there was one), date of admission, full name, age, marital status, occupation, previous place of abode, by whose authority sent, religion, date of discharge and observations (if any).

Initially the Northcote Asylum, located on St George’s Road where Northcote High School sits today, was run by Dr Charles McCarthy who used financing from citizen donations in addition to a Government grant and maintenance fees from patients. The Royal Commission on Asylums for the Insane and Inebriate 1884-1886 recommended that the Asylum be taken over by the Government.5 After legal disputes regarding this, it finally was taken over by the Government under the Inebriates Act, much to the dismay of Dr McCarthy, as evidenced in his letter to the editor, published in the Advocate on the 20th of February 1892:

“May I ask for a small space in your valuable paper to show the wrongs I have suffered at the hands of the Government in being deprived not only of my property, but even of the benefit intended me by the Supreme Court—that is, my position as medical superintendent and secretary to the Inebriate Retreat, Northcote. On the first of last July I was forcibly removed from the establishment which I had founded and conducted during eighteen years...”

The Asylum was closed altogether in October 1892 by order of the Governor-in-Council as a result of low numbers and financial hardship resulting from the depression. The buildings were demolished in 1926 to make way for Northcote High School.

This article from the Illustrated Sydney News, published on the 21st of June 1890, illustrates the state of the Asylum in 1890 and the Doctor’s thoughts on alcoholism, what causes it and how to treat it.

“My own opinion is that men and women of any age can be cured if sufficient time is afforded.”

During its operation, 650 people were treated at the Northcote Inebriate Retreat.

Inebriates Act

After a Victorian Government appointed committee inquiry into cures for sobriety, the 1904 Inebriates Act was passed. Susanne Davies said:

“This legislation incorporated existing provisions allowing for the compulsory and voluntary confinement of inebriates in government licensed institutions, but also extended the powers of police and magistrates. Under the new law, a magistrate could order an individual convicted of three drink‑related offences within a single year to be detained in a licensed institution for up to twelve months."

Within our evidence files related to the committee's work you can find very sad and confronting letters from people desperate for help for themselves and/or their loved ones. The Committee had advertised for people to submit to treatment and be observed for the purposes of the inquiry. Harriet Shepherd wrote in 1902 offering her husband as a subject who was at the time serving a prison sentence at Melbourne Gaol, presumably for drunk and disorderly. She says that he had been a 'confirmed drunkard' for fourteen years and in and out of Police Court five times.

"He has a great desire to do well and to conquer this habit that has ruined his life... but seems unable to fight against the terrible craving that possesses him."

She goes onto say that his drinking had become so bad that the doctor at the Gaol hospital had said if he had continued without imprisonment any longer he could have died from the amount of alcohol he'd been consuming.

A basket maker wrote in 1901 of his attempts to 'get off the drink' for six months with no luck and hoped the Committee would help. His handwriting was so bad, the result of shaky hands, his wife re-wrote the letter for him. A woman wrote in about her brother who had been addicted to whisky for six years. Another woman described her life of misery which could be happy if only she could resist alcohol. A man named Fleming wrote of his wife after his own cures failed to work on her. Another man asked for anonymity if he was to undergo treatment as he was a school master. He said he worked 10 to 14 hour days and drank upto four glasses of spirits per day, usually toward the end of an evening when the 'desire for a glass of spirits becomes almost resistless." He said that his habit was hindering his abilities to do his job.

The Lara Inebriate Retreat opened in 1907 after this inquiry and resulting Act.

Lara Inebriate Retreat

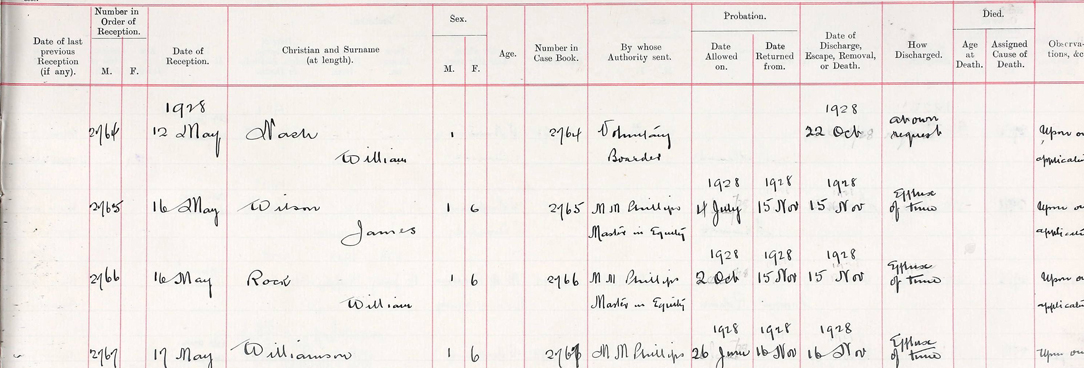

The Register of Patients 1907-1937 at Lara is included in the newly digitised files available on Ancestry. The register includes date of previous admittance (if there was one), date of admittance/reception, full name of patient, a case book number (which should correspond with the person’s case book within our collection), by whose authority sent, probation dates, discharge date and other observations.

The Lara Inebriate Retreat housed both voluntary and in-voluntary patients.6

The desperation of family members of patients at Lara is evident in correspondence files at PROV. This letter from the doctor at Lara to the Superintendent reveals the struggles of a wife dealing with her husband who refuses to return to continue treatment at the institution.

It reads:

"A very awkward impass has arisen. Yesterday Mrs A phones me to come to Toorak at once and seemed in great distress. When I got to the house I found A had the household terrorised by threatening to shoot himself if he had to return to Lara. after a long discussion with both I tried to make terms with him if he would pledge himself total abstention. He would not do so and rushed from the room... He burst out weeping and declared he would never again return to Lara, that his brain was going... Finally I saw no way out of the difficulty but to compromise with him. He agreed to remain a teetotaler for a fortnight further and after that he would be most abstemious; and agreed to voluntarily return to Lara if he took drink in excess on any occasion."

The current-day scepticism sometimes shown when a person in the public eye attends rehabilitation after a scandal seemed to also be the case in 1928, when a man named William Nash – shown in the register – was admitted to Lara. He is discussed in detail within correspondence files. A letter from the Inspector General of Inebriate Institutions to M T Donnellan of Lara, says that the Truth office was calling, alleging that Nash was faking his symptoms to avoid arrest for illegal acts including misappropriation of funds. Donnellan put the office of the Truth and the Inspector General at ease with his response.

“This patient was admitted here on the 12th May last. On admission he was in a bad way and for the first fortnight an attendant was with him day and night. Although he has improved considerably and is able to move about, he is still far from normal. I enclose extracts from Dr Godfrey’s notes in the Case Book.”

The notes reveal daily recordings of Nash as disoriented, dazed, confused, semi-comatose with eventual improvement over the course of a month to the point where he is “now almost normal” but still confused as to his financial and social affairs, which no doubt were not good! By the looks of the register it seems he was released in October, presumably with a mess of trouble awaiting his return to society.

In 1926 it was reported in the Annual Report of the Inspector of Inebriate Institutions that 155 men had been admitted to Lara in the year, with an additional 46 women admitted to Brightside (Lara’s female equivalent). Relapses accounted for 79 of the admissions. Up to that point 589 or 54.7 per cent of patients had recovered.

Lara was closed on 10 September 1937 - during a period of doubts around the effectiveness of Inebriate Institutions. The 50s and 60s saw optimism around treatment for alcoholism resurface with the emergence of new treatment services. The 1970s and beyond saw calls for other measures to combat alcohol abuse in Australia.5

Today

It’s no secret that Australia still has a major problem with alcohol. Alcohol kills 15 Australians every day and around 1 in 5 Australians over 14 years of age drink at levels that put them at risk over their lifetime.7 Long term effects of alcohol use include dependence and financial, work and social problems, in addition to depression, liver disease and cancer to name a few.8

Today’s alcohol and drug treatment services, including residential rehabilitation centres, assist approximately 40,000 Victorians each year.9

More information about treatment options and access in Victoria can be found on the Vic Health website.

The Alcohol and Drug Foundation also has a list of support and treatment services on their website.

Viewing the records

View the scanned asylum patient records on Ancestry via your own paid account, or visit one of our reading rooms or your local library to view the records free of charge on the public computers. The original records are also available to order in hard copy for viewing in our North Melbourne reading room at the Victorian Archives Centre.

Other records related to asylums, including correspondence and evidence files used in this blog post, can be ordered for viewing in our North Melbourne reading room at the Victorian Archives Centre.

References

1 http://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00050b.htm

2 https://theconversation.com/a-brief-history-of-alcohol-consumption-in-australia-10580

4 https://researchdata.ands.org.au/northcote-inebriate-asylum/492604

5 Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History by Jack S Blocker, David M Fahey and Ian R Tyrrell, 2003.

6 https://researchdata.ands.org.au/lara-inebriate-retreat/491241

7 https://adf.org.au/insights/alcohol-epidemic/

9 https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/alcohol-and-drugs/aod-treatment-services

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples