Author: Public Record Office Victoria

Record of the Month - August 2013

Great White Fleet - 105 years on

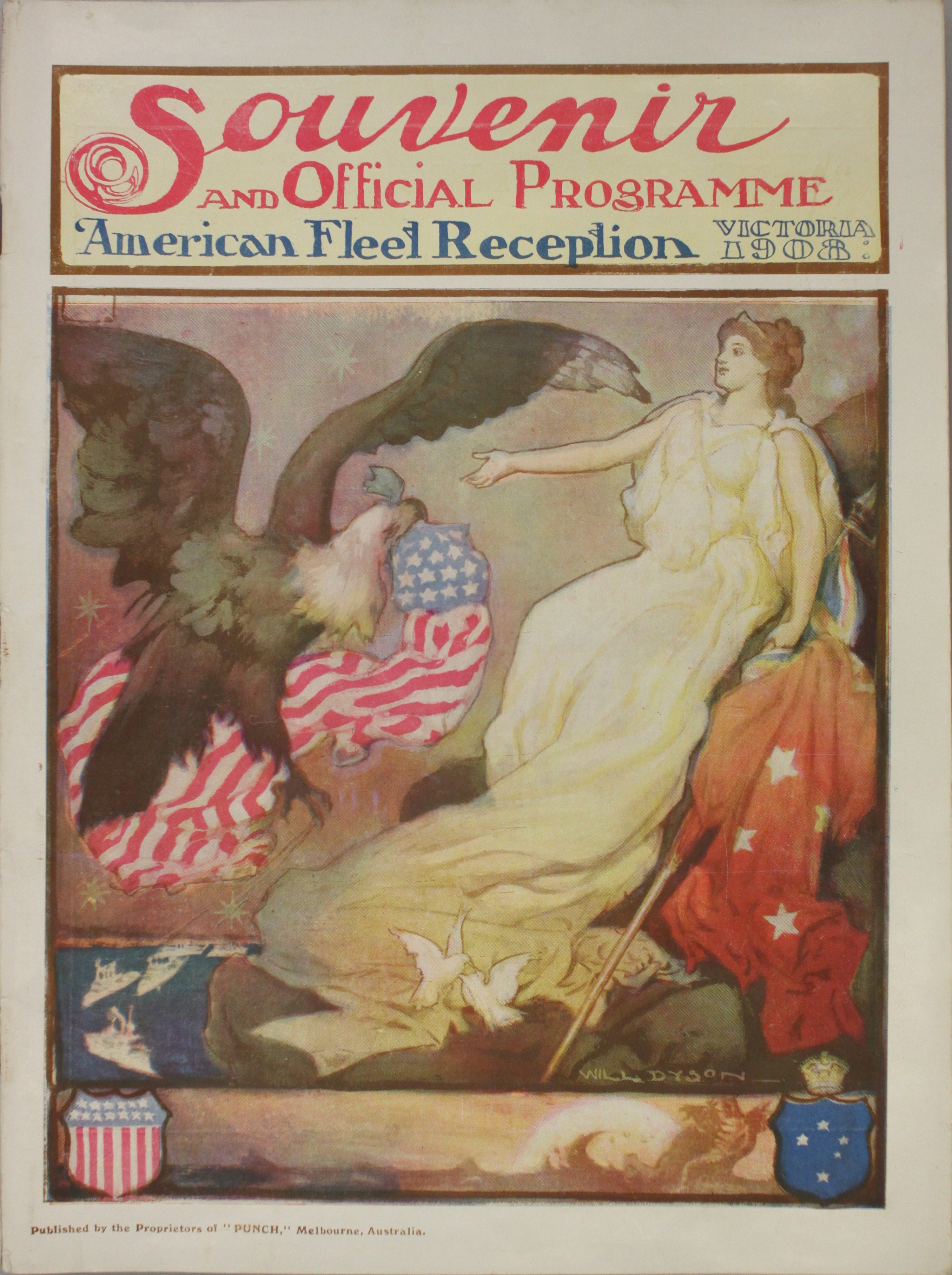

On the morning of 29 August 1908, sixteen white-hulled battleships carrying fourteen thousand sailors and marines of the United States’ Atlantic Fleet steamed through the Rip and into Port Phillip Bay.

The ‘Great White Fleet’, as this flotilla became known, had been launched on its circumnavigation of the globe by President Theodore Roosevelt. The cruise was a propaganda campaign of extraordinary proportions – a showcase of naval power beyond anything ever before attempted during peacetime. It was also a practical and strategic exercise, at once testing the battle-readiness of the US navy and demonstrating its ability to patrol and protect the US west coast and Pacific interests.

Despite the fact that several ships were antiquated, their arrival had a powerful impact on Australia, politically independent for seven years but still reliant on British military muscle to guarantee its independence.

Concern about this reliance was exacerbated by Britain’s decision to withdraw its Pacific naval presence, and the destruction of the Russian navy by the Japanese during the Russian-Japanese war of 1904–05. The symbolic victory of an Asian navy over a ‘European’ power, coupled with the fact that there was still no formal Australian navy, would have made the presence of the US battleships even more significant.

Victoria pulled out all the stops for ‘Fleet Week’, and records held at PROV show the scale and scope of the welcome: newspaper reporters waxing lyrical about the ‘Turner-esque’ picture of the ships steaming past Dromana; sixteen thousand copies of maps, guide books, railway schedules and souvenir programs printed and distributed to the ships’ crews to guide them around Australia’s biggest city; hundreds of thousands of extra train travellers swarming into Williamstown to see the Fleet, and into Melbourne to meet the sailors; young cadets marching five days from Ballarat to take part in the welcome parade; and of course sailors ‘with a girl on each arm’.

Melburnians laid out the red, white and blue welcome mat for the new Pacific sea power. The records describe months of preparations by state and city officials to celebrate the visit. Suppliers of bunting and decorations rushed to offer their wares, and scores of Victorian town councils, as well as public and private clubs and societies, wrote to beg the State Cabinet American Fleet Reception Committee to consider them when scheduling the official program of events. The Victorian Railways offered cheap excursion trains from country centres, and free travel to the sailors, and carried record numbers of passengers during Fleet Week. Victorians and Americans mingled, as thousands visited the Royal Agricultural Show, where they saw dumbbell and wand exercises by state school students, and flocked to the racing at Flemington, where the Washington Steeplechase and Fleet Trotting Cup were run. The Zoo, the Aquarium and ‘Glacarium’ all offered free entry to visiting sailors.

While country Victoria travelled into the city to meet the sailors, the sailors journeyed out to see the country. At the invitation of a local American citizen, some sailors made the long trip to Mirboo North in East Gippsland, where they saw wood chopping and ‘Aboriginal boomerang throwing’ and took part in foot races (a handsome silver-mounted emu-egg trophy was carried home by the victor) and a tug-of-war. Others travelled to Bendigo and to Ballarat, watching Australian Rules Football and visiting the mines.

In such a flurry of welcome and activity, there were problems, both comic and tragic. The failure of an American officer to pass on an invitation meant that only seven sailors turned up to a reception and dinner at the Exhibition Buildings, where catering had been laid on for 2,800. Two sailors died in train-related accidents, with newspapers quoting a comrade as saying ‘we lose a few in every port’.

Spruiking of the state’s liveability was also in evidence. Visitors were proudly told that, in Victoria, ‘All railways … and supplies of water are state-owned’ and that we had ‘Factories Acts and Wage Boards, Pure Food Laws, Compulsory Vaccinations’ and ‘Manhood Suffrage’ – the Fleet had arrived just three months shy of Victoria awarding the vote to women.

This combination of attractions no doubt contributed to the sailors’ view that Melbourne was the ‘best port of call’ in their 14-month, 20-port call, round-the-world voyage. So convinced were the visitors of Victoria’s, and Australia’s, attractions that 221 deserters jumped ship in Melbourne. The USS Kansas stayed on for a number of days after the rest of the Fleet departed for Albany, Western Australia, in part to wait for a mail steamer, but also to collect stragglers. A reward of $10 was advertised for the successful return of each deserter to his ship, but the conditions of the reward were so difficult to meet that no money was ever paid. By the time the Kansas finally weighed anchor and bade farewell to Melbourne, more than half the deserters had been recovered, but about a hundred men remained behind to start a new life.

Flamboyant press descriptions, bureaucratic reports, orderly minutes, colourful programs, boastful guidebooks, and stacks of correspondence – including telegram upon telegram organising, confirming, rearranging and renegotiating functions, are the records left in the wake of the Great White Fleet’s visit to Victoria. These and more are part of Victoria’s state archives – call in to PROV and have a look at them some time soon.

VPRS 10370/P0 Unit 7 - Welcome to the Australian Fleet Poem

VPRS 10370/P0 Unit 7 - Letter regarding the transport of State School Cadets

References

PROV, VPRS 1163/P0 Inward Correspondence Files (Premier’s Office), unit 483, file P/08/4476 Papers re visit of American Fleet in 1908

VPRS 10370/P0 Records Regarding the American Fleet Visit, units 1–7

(unit 7 contains newspaper clippings, programs and guidebooks)

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples