Author: Amber Graciana Evangelista

The town of Walhalla

Walhalla is a picturesque mountain town nestled into the Baw Baw Ranges of the Gippsland District. Walhalla was the centre of one of the great goldfields of Victoria when it was founded as a gold-mining community in 1862. It was home to 4,000 people and produced some 55 tonnes of gold.

The town itself was small: settled on a small section of the Stringer Creek Valley, buildings were mostly confined to one main street that followed the valley’s creek.

The Walhalla Institute is born

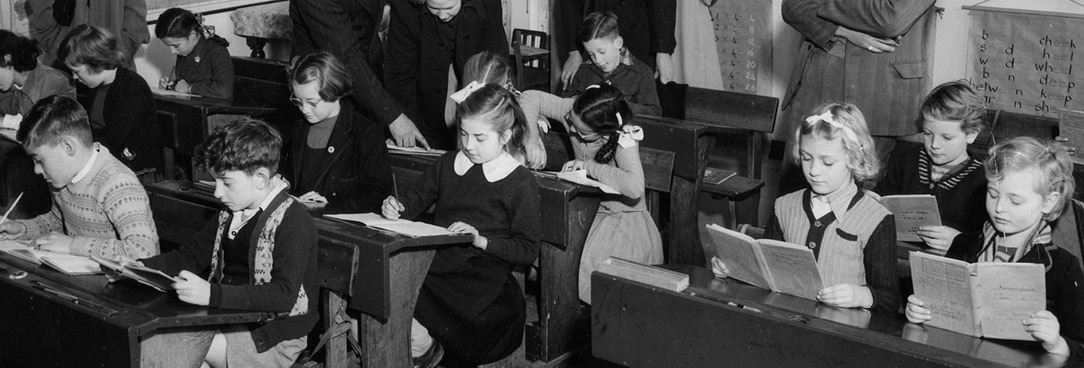

Although conditions were rough and the town was isolated, during its boom years Walhalla was a vibrant town and community. By 1867 the population was more than large enough to support a local school, which opened under the super-intendancy of Mr George Christie. This school, known as the Walhalla Institute, taught 50 students and functioned as a church on weekends.

Within a year, the school’s roll had expanded to 90, and a new teacher was needed to oversee the rapidly expanding school. The role was advertised in Melbourne newspaper The Argus on the 1st of June 1868. Henry Thomas Normanton Tisdall, an Irish immigrant from Melbourne, applied and took the position.

Tisdall was a commanding figure and a central member of the community who taught the school for close to 18 years.

After his departure the school had difficulty finding steady staff due to its remote location, poor road access and cold and damp climate. Tisdall himself was required to assist in the process of hiring a new teacher. One applicant, Miss Mary Anne Dillsworth, was the subject of several letters between Tisdall and the Education Department.

Hiring Miss Dillsworth

On the 28th of January 1886 Tisdall wrote to the department:

“Mary Anne Dillsworth passed in all subjects…excepting needlework. The school does not seem to have examined her in that subject.”

Although Miss Dillsworth had passed all other examinations with a 3rd class order of merit, was able to provide past inspectors reports and a letter of recommendation from her previous school, the absence of needlework certificates proved rather alarming to the Department.

Tisdall, however, provided written support for Miss Dillsworth and a compromise was reached. The Education Department requested:

“Ms Dillsworth should forward specimens of her needlework” from which her aptitude could be judged.

A miniature woollen sock and cuffed cotton sleeve were promptly forwarded to Melbourne, and Miss Dillsworth’s competency was established.

Miss Dillsworth and Mr Tisdall’s communications with the Education Department were in some ways typical of the rural school experience. Staffing and managing schools in rural areas was often about compromise; although the submission of sewing samples was not a typical method to prove qualification, Walhalla’s isolation made compromise necessary.

Written by Amber Evangelista based on records* discovered while undertaking research for School Days: Education in Victoria. With special thanks to Bernard Bolch of the Walhalla Heritage and Development League for assistance.

* VPRS 640 P0 Unit 551: Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence Series.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples